Did you ever get interested enough in a particular subject that you would gladly spend hundreds if not thousands of hours researching that subject?

That pretty much describes my passion for the story of Cassin Young.

I can’t remember when I started researching and writing a proposed book about Cassin Young. It seems like it’s been at least eight years. The work done included diving into the national archives, the Naval Historical and Heritage web site, countless hours chasing rabbits down holes and looking for every shred of information possible.

The original plan was to publish the book and use it for a platform to do public talks about the subject.

But after eight years of working, the publishing part has not come to pass. As I was walking on this bright blue South Carolina day, two thoughts came into my head. First, I was probably never going to publish the book in printed form. Second, even if I did, my life and health situation would probably restrict me from traveling to all of the places that are key to the story. So, if the story is ever going to be told, I may as well use the platform I have been using for the last decade plus… the blog you are reading now.

So, over the next few weeks, I am going to use this platform to tell the story from my perspective.

I have to tell you that one of my early collaborators backed out after reading an early copy of the work. Apparently some objectional materials were included in the first few chapters. But my view has never wavered that when you tell a story, you include all the rough parts as well as the attractive parts. I believe that life is never completely smooth and neither should a good story telling be smooth.

Counting the introduction, prologue and epilogue, there are twenty-three chapters. I divided it up into four sections

(There is a total of around fifty thousand four hundred words plus or minus a few)

- Section One – Naval Academy Years

- Section Two – World War One and the Submarine Life

- Section Three – Washington Naval Treaty and the Pre-War Years

- Section Four – Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal

Having set the table, here is the introduction I had planned and the prologue. Chapters will follow in the weeks to come.

Every Moment Mattered

Introduction

Ask any submariner the one thing they hear the most from people who have just learned of their role as a submariner and I would be willing to bet that the most common response would be “Oh, I could never do that.”

In the more than fifty years since I rode my first submarine, I have heard that expression more times than I can count. To be honest, it doesn’t surprise me. The thought of being cooped up inside a steel tube for weeks and months at a time with no access to the outside has to be pretty daunting. Plus, you are going to be inside that steel tube while traveling hundreds of feet below the surface without a way to see where you are going.

For those that do traverse the sea in submarines, there are many traits and characteristics that make them special. First and foremost, all submariners are volunteers. Some may be a bit coerced from time to time, but at one point in their life they had to put their name on a dotted line saying they were volunteering for sub duty. Second, they are some of the most highly trained sailors the Navy has in its ranks. There are so many specialties on submarines because of the highly technical nature of the equipment that nearly all of the crews went through some kind of training to get there and continued training after they have arrived.

Finally, there is a matter of courage. When I recently asked a random group of submariners how they would describe themselves, courage was one of the least common words that they used. Maybe it’s not been true for all generations of American submariners but terms like cocky, arrogant, sarcastic, risk takers and so on would be more common ways they describe themselves. Also, words like dedicated, determined and driven rise to the top of the lists.

But face it. They all know about the inherent dangers of riding beneath the waves and they do it anyway. In my mind, that is another way of demonstrating courage.

The early pioneers of the submarine service faced great challenges that have diminished somewhat through the decades but have never been completely eliminated. Technology was one of the strongest barriers. Cassin Young graduated from the Naval Academy in 1916 which was exactly sixteen years after the first submarine entered service in the US Navy. The early boats were gasoline powered on the surface and had limited battery storage. They were mainly envisioned as harbor defense units and could not generate enough speed to be a credible threat against fast moving surface ships.

But when Young’s class graduated, technology was on the march. Stronger ways of building the boats, diesel propulsion on the service, improved batteries and so much more helped the submarines to gradually evolve into semi-independent vessels with greater and greater capabilities. Young served in improved boats that dove to deeper depths and became closer to the submersibles that would help win World War 2.

Make no mistake, however. These pioneers exemplified a rare brand of courage. They would need that courage as some of the early boats fell victim to the dangers of the age. Collisions, flooding and fires were all part of the submarine game. Even with improvements, that remains a challenge today.

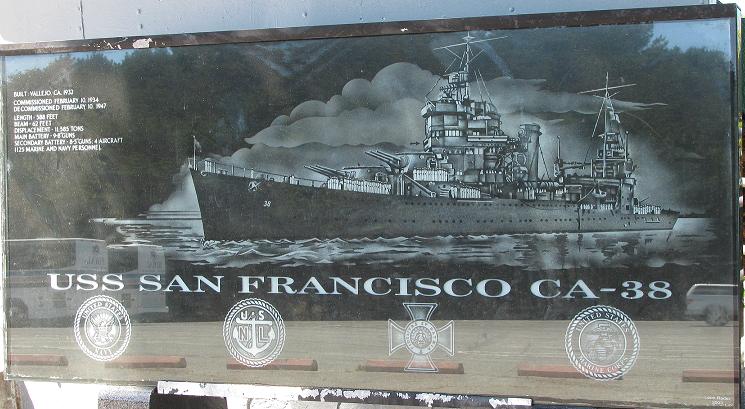

My third submarine was the USS San Francisco (SSN 711). It was far different than the first two boats that I served on. I arrived for duty on the boat just after it was put in the water during new construction. My first two boats were being built when I was a very young boy and had many thousands of miles beneath their keeps when I later reported aboard. But this boat was new and had an entire life of adventures ahead of its bow. It was great fun to help build her and watch the crew come together. We were a proud group and we were part of a larger heritage. The name USS San Francisco was used before in the annals of Naval History. But the cruiser which bore that name and the hull number CA 38 left a mark on the world at a time when heroes were truly needed.

When our submarine was commissioned, she was eventually sent to her new home port in Hawaii. On her way there, the boat stopped at a few ports along the way but none more dramatic than the visit to her home city, San Francisco California. When she arrived in the fall of 1981, the city came out to greet her as part of Fleet Week. She had a welcoming committee all the way in from the Golden Gate (some friendly, some not so much). The mayor of the city was Diane Feinstein and we were feted to a number of events. The people of the city were gracious and some of us got to meet with a group that had served on the cruiser San Francisco. It had only been thirty-six years since the Second World War had ended so there were a number of the men were still alive at that time.

One of the events we shared was a visit to the park overlooking the entrance to the bay where the remains of the bridge of the CA 38 were permanently enshrined. This monument was made up of the shell pierced bridge structure that had been cut away and replaced after the night battle of Guadalcanal on November 13, 1942. During this attack, Admiral Dan Callaghan, Captain Cassin Young and a number of their staff members were killed while engaging a superior force. While the memory of that breezy San Francisco day is still in my mind, the curiosity about the men who died that night stayed dormant for many years.

In the lead up to November of 2017, I became interested in learning more about one of the men on the ship that night, Captain Cassin Young. I had long ago studied the battle itself using every available report the Navy recorded and many fine books by some of the best historians in the field. But Captain Young’s story seemed incomplete. A quick search reveals that he is well known for an event that happened on December 7th where he performed some pretty heroic feats resulting in a Medal of Honor Award. But in this battle, he gave his life and it seemed to me that the full story of Captain Cassin Young had not really been told.

That began a search to piece together his story. What I found surprised me and made me be more in awe of a man whose full legacy deserves a fair hearing. The information and my knowledge of the Navy’s ways and means opened my eyes to a new way of looking at a man who helped make naval history and defend a nation for his entire adult life. This story is about the man who faced danger the only way a man like him could. He stared it in the face and demonstrated what courage really means.

In a life filed with many memorable moments, in his case, Every Moment Mattered. In a world where we are sorely lacking heroes, the compelling case of Captain Cassin Young’s needs to be told.

Prologue

THE TIP OF THE SPEAR

On the 16th of September in the year of our Lord 1943, Eleanor McFadden Young and three of her four children participated in the launching of the USS Cassin Young, a destroyer named after her late husband. The children, Eleanor, Mary Ann, and Stephen looked on as their mother smashed the bottle of champagne into the bow of the ship. Her oldest son, Lt. JG Charles McFadden Young was not in attendance since he was serving on submarines in the War in the Pacific. It was a family tradition that a Young would not only be an officer but also serving on submarines since Cassin had been a submarine leader for much of his thirty years career.

The ship was built at the San Pedro shipyards of the Bethlehem Steel Company in California. Eleanor was given the honor of being the ship’s sponsor.

The local paper (Coronado Eagle and Journal) recorded on September 16th that the late Captain Young had been a hero at Pearl Harbor and in South Pacific naval battles. With the swiftness that often accompanies newspaper reporting, his death at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was mentioned but with few details. Nor was it mentioned that he had been awarded the Medal of Honor.

His death in combat and his role in the Guadalcanal stated that he was the commanding officer of the cruiser USS San Francisco. While in that role, he led his ship against a superior force of Japanese warships that included two battleships, a cruiser and numerous destroyers. This superior force was being sent to bombard the Marines, Army and Navy men that were clinging on to the island. The Japanese wanted to expel the tenacious fighters once and for all and complete their conquest of that part of the Pacific. It was a high stakes battle and the Americans were fiercely outnumbered.

Cassin Young was one of four senior officers killed during that battle. Admiral Callaghan was in command of the force and had known Young for a long time. Admiral Scott on board the Atlanta was also killed that night. He was a classmate at the Naval Academy with Callaghan. Captain Lyman K. Swenson was the commanding officer of the USS Juneau which survived the first part of the battle only to be killed in a blinding flash the next morning. Swenson was a Naval Academy Classmate of Cassin Young.

Previous Honors

On January 10th, 1943, a Naval War Memorial was unveiled at the Naval Academy Chapel. The Coronado Eagle and Journal reported in its January 21st edition that a ceremony was conducted in the chapel to honor members of the class of 1916 who had died up to that point in the war. Cassin Young and Captain Lyman K. Swenson were classmates.

From the article:

“A solemnly religious ceremony took place on January 10th at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis Maryland, when a war memorial to the officers in the class of 1916, killed in this war, was unveiled in the presence of the Regiment of Midshipmen, members of the Class of 1916 stationed in the vicinity, their families, and as special guest of honor the Secretary of the Navy, the Honorable Frank Knox and many wives and families of the deceased members of the class.”

The Class of 1916 was a very special group since they were among the first to go through a radically different course of instruction and a focused attempt to try and bring the institution into a more professional modern naval culture. Special emphasis was placed on Captain Cassin Young and his story.

“The memorial has special and worldwide significance at this time. A member of the class of 1916, Captain Cassin Young of Coronado, commanded the valorous cruiser USS San Francisco in the night battle in the Solomon’s, November 13-15. With Captain Young on the ship’s bridge when he was killed by enemy gunfire was Task Force Commander Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, also killed by the same gunfire.”

Heroic Names for Heroic Ships

Three of the warriors from that night battle were also honored in their death by having new destroyers named after them. Cassin Young, Daniel Callaghan, and Lyman K. Swenson. Admiral Scott would have to wait until decades later before a destroyer bore his name.

The USS Callaghan (DD-792) was launched a little over a month before her sister ship Cassin Young on 1 August 1943 by Bethlehem Steel Co., San Pedro, Calif.; sponsored by Mrs. D. J. Callaghan; commissioned 27 November 1943, Commander F. J. Johnson in command; and reported to the Pacific Fleet.

As the sister ships were being launched in California, the USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD‑729) was laid down 11 September 1943 by Bath Iron Works, Bath, Maine. She would be launched on 12 February 1944; sponsored by Miss Cecelia A. Swenson, daughter of Captain Swenson; and commissioned at Boston Navy Yard 2 May 1944, Comdr. Francis T. Williamson in Command.

The destroyers Callaghan and Young would serve together again all across the Pacific. But the fortunes of war were not kind to either the ships or to a good portion of the brave men that sailed on them.

The Japanese had been losing battle after battle after Guadalcanal. But each battle was costly for both sides. As the American fleet became more robust with the infusion of newly built ships of every kind, the Japanese continued to shrink. Key battles in 1942 had decimated their air power at sea and the growth of American air, surface and submarine capabilities took an enormous toll on the Japanese fleet. The stranglehold of submarine warfare made it more and more difficult for the homeland to obtain the needed supplies form her far flung empire.

The island hopping campaign of the American Navy also brought the new fleet closer and closer to the Emperor. The Battle of Iwo Jima was bloody and expensive to all sides. Plus, this was now in the Japanese home territory. The reversal of fortunes from just a few years ago must have been stunning to the high command.

The Kamikaze

So it was even more crucial as the largest allied fleet ever assembled in the Pacific approached Okinawa. From that standpoint, the use of a new type of weapon was critical. The Kamikaze attack was framed after a miracle that had saved the Japanese from invasion centuries ago. Kamikaze means Divine Wind. Kamikaze is a Japanese word literally meaning “divine wind” taken from the word ‘kami’ meaning “god, providence, divine” and the word ‘kaze’ meaning “wind”. The origin of the word derives from an event in 13th century history of Japan when a Mongol invasion fleet under Kublai Khan was destroyed by a typhoon. The typhoon was believed to be a gift from the gods that was granted after the emperor prayed for divine intervention.

The widespread use of this new type of tactic began in 1944 at the Battle of Leyte Gulf. But as each move by the American task force came closer to Japan, the attacks and tactics intensified.

The peak period of kamikaze attack frequency came during April–June 1945 at the Battle of Okinawa. On 6 April 1945, waves of aircraft made hundreds of attacks in Operation Kikusui (“floating chrysanthemums”). At Okinawa, kamikaze attacks focused at first on Allied destroyers on picket duty, and then on the carriers in the middle of the fleet. Suicide attacks by aircraft or boats at Okinawa sank or put out of action at least 30 U.S. warships and at least three U.S. merchant ships, along with some from other Allied forces. The attacks expended 1,465 aircraft. Many warships of all classes were damaged, some severely, but no aircraft carriers, battleships or cruisers were sunk by kamikaze at Okinawa. Most of the ships lost were destroyers or smaller vessels, especially those on picket duty.

The Tip of the Spear.

Being on a destroyer in the middle of one of the most critical invasions of the war had to have been challenging. In front of you were the home islands of Japan that housed uncounted amounts of airplanes that had been held in reserve for just this moment. At any moment, the skies above you could be filled with fast- and slow-moving planes that had one purpose – sink American ships.

Behind you were the soldiers and Marines slogging it out with a fiercely motivated Japanese Army. They were entirely dependent on the massive force of the warships supporting them in their quest as well as the comfort of knowing hospital ships were waiting for them. The ammunition for their guns, the food they would eat, and the water for life were all on those ships. Too many times in the wars in the Pacific, supplies made the difference between life and death. But someone needed to guard those ships from this devastating new enemy. That someone was those fast destroyers like the Callaghan and Young.

Picket duty was an important part of the American strategy. Fast moving destroyers equipped with radar were assigned positions at the leading edge of the fleet and would report the incoming waves of attackers. They were also equipped with the five inch guns and special shells that had proven so effective during the battles that came before.

But this defense came at a cost.

Since most of the airpower was dedicated to protecting the battleships and aircraft carriers, the destroyers often found themselves with little cover. Plus, the pace of the attacks was swift and furious. Even the most well prepared crew could be overwhelmed by the sheer numbers and intensity of the attacks.

On the 9th of July in 1945, the USS Callaghan took station on the embattled radar picket line during the Battle for Okinawa. On the 28th of July she drove off a biplane intent on suicide with well-directed fire. The plane was attacking wood-and-fabric Yokosuka K5Y biplane. The aircraft survived the first approach because the proximity fuses were ineffective against its wooden fuselage.

When the determined plane returned, skimming low and undetected, it struck the Callaghan on her starboard side. The plane exploded and one of the plane’s bombs penetrated into the after engine room. The damaged destroyer quickly flooded, and the fires which ignited antiaircraft ammunition prevented nearby ships from rendering aid. The USS Callaghan sank at 0235, 28 July 1945, with the loss of 47 members of her brave crew.

Callaghan received eight battle stars for World War II service.

The 28th of July was a bad day for the USS Cassin Young.

She was part of the same group of picket ships that were patrolling. The ferocity of the attacks was enough to almost overwhelm the defenders that day.

Cassin Young was no stranger to the kamikaze. On April 1, which was the day of the Okinawa invasion, she provided fire support in the assault areas, then took up radar picket duty. On 6 April, Cassin Young was subjected to her first desperate kamikaze attacks with which the Japanese gambled on defeating the Okinawa operation. Two near-by destroyers, whose survivors Cassin Young rescued, were sunk. On 12 April, it was Cassin Young’s turn, when a massive wave of kamikazes came in at midday. Her accurate gunfire had aided in downing five would-be kamikaze planes when a sixth crashed high up into her foremast. This plane exploded in midair only 50 feet from the ship. Casualties were miraculously light; only one man was killed and one other wounded.

During the engagement on July 28th, Cassin Young assisted in splashing two enemy planes, and rescued survivors from the sunken ship. The next day, she was attacked by a low-flying airplane which struck her starboard side.

A tremendous explosion amidships was followed by fire, but in an impressive damage control operation, her men restored power to one engine, battled the flames under control, and had the ship underway for the safety of Kerama Retto within 20 minutes. Twenty-two of her men were dead, and 45 wounded. For her determined service and gallantry in the roaring fury of the Okinawa radar picket line she was awarded the Navy Unit Commendation.

After repairs, Young would sail home for San Pedro once more where she would finish the war and be decommissioned. Her service life would restart during the Korean War, and she continued to carry the brave name of Cassin Young for another decade.

Today

The ship is now a national museum ship in Boston Massachusetts. But the story of the brave man who she was named for has never been completely told. The chapters that follow will take you through his early years as a Midshipman and some of the challenges he and the Navy faced as it grew into the modern fighting force that would help save the world from the tyranny that spread across the globe in the 1930’s and 1940s. His story also includes his life as a submariner during the critical period when submarines grew into a powerful force that would ultimately help tip the balance in the war. The last eleven months of his life are remarkable for so many reasons. He was at the thirty-year mark of a fine career when circumstances placed him at two critical moments in the history of naval warfare.

At the January 1943 dedication of the Naval Academy War memorial after his death, a tribute was read that had been written by one of his 1916 classmates:

“To all of us who have known Ted Young, his loss comes as a shock. For his gallant and heroic sacrifice, the heart of every member of the Class pours out to his widow, his mother, his children, and his family their inexpressible grief and offers heartfelt consolation to those he left behind. The memory of Ted is immortal, and he stands out predominantly as the embodiment of all the superb virtues of a faithful father, a gallant naval officer; a loyal and loveable classmate and friend. A real man – in brief, a hero. May his soul rest in peace.’

When you see the sum total of this man’s life, it becomes obvious that time has hidden the true story of an American Hero. In all of these stories that follow, we are reminded that in all of our lives, every moment mattered. This is a story of honor, courage and commitment in the face of extraordinary challenges. This is the story of Cassin Young and the Navy that helped win World War 2.

Next up: Chapter 1 Plebes is Plebes

I have a huge favor to ask… if you enjoyed what was written, please drop a note or click on the like button. I would greatly appreciate that

Mister Mac

Hey Bob, I remembered a previous article or email you posted/or sent me about Cassin Young and immediately stopped what I was doing and read the whole article ON MY PHONE. It was fantastic and I can’t wait to read “The Rest of the STORY” (as Paul Harvey used to end his radio broadcast”). Norm

Absolutely behind your work here. Last year the wife and I went up and down the east coast (new to us as we are west coast folks). When in Boston we did the obligatory tour of the USS Constitution. Yes, it was well worth it… but my wife was tuckered out and declined to go have a look at “that destroyer down the pier”. She parked herself on a bench with a book, and I stumbled over to visit the Cassin Young. I’m not going to steal your thunder, but OMG. It still gives me chills thinking about where I was standing, and what she had been through. Looking forward to your installments.

ICFTBMT1(SS) Maxey, USN (retired)

I have always enjoyed reading your stories. I missed seeing you

As Norman says above, I look forward to reading “the rest of the story”. Enjoyed meeting you and your wife in person at the USSVI convention. Martha

I had only been to one convention before but really appreciated the chance to meet you both in person as well as others. Hopefully we can meet again

Bob