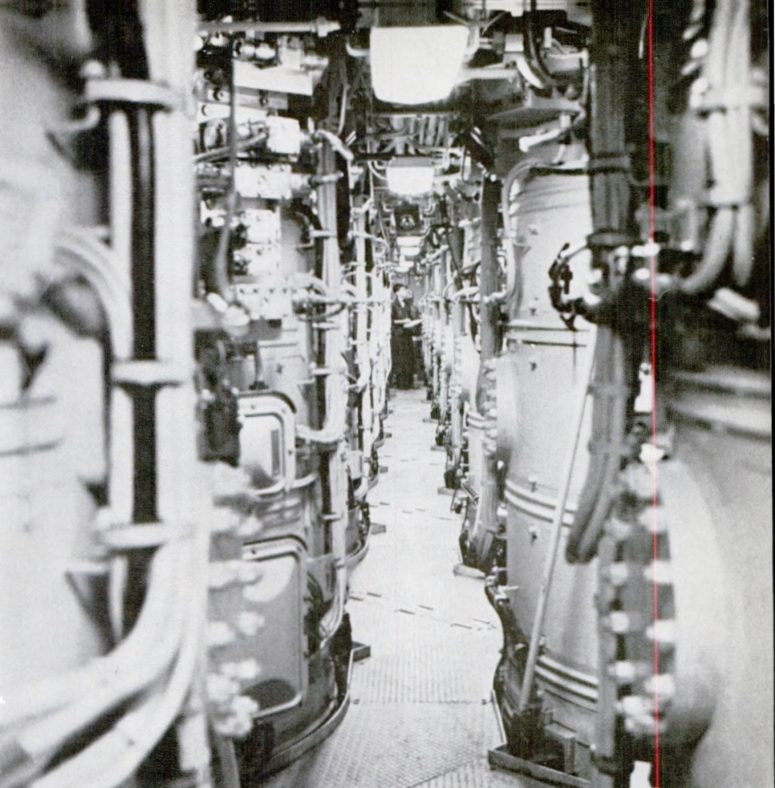

I have to be honest and admit that I never looked inside the missile tubes on either of my FBM submarines. I know there was something inside all of the tubes because of the great deal of work required to keep them ready for use if the President called on us. But as an A-Ganger, it really wasn’t my responsibility to do much more than make sure the air systems and hydraulics were available and working in case they were needed. Okay, to be fair, we did a lot more than that, but mostly we were there to make sure that the mission could be completed as designed.

On my first boat, we had a library in the upper level missile compartment. That was my hangout when I need some quiet time. After I got qualified, it was my favorite place to be since I had never read any of the hundreds of books that were located there. The books that intrigued me the most were science fiction books. Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov still remain some of the greatest writers I can ever recall but I did spend a lot of time reading a futuristic novel called “1984” by George Orwell. I remember thinking at the time how strange that book was and how much it would always remain a work of fiction.

I also thought I would never need a computer in my house.

This story is a great read that captures the fifth anniversary of the deployment of the 41 for Freedom fleet. It gives a close up look at the challenges facing the men who designed the system that would someday emerge as the premier element of the strategic nuclear triad. It’s amazing to read how they overcame each struggle on their way to achieving seemingly impossible goals.

As I think back to those days reading the science fiction novels that same from such brilliant minds as Heinlein and Asimov, it is easy to make a juxtaposition with the development of Polaris. I am sure that many people at the time thought that is just couldn’t be achieved. And yet, it was.

Polaris A3 Deploys in Atlantic and Pacific (ALL HANDS 1965)

The DEVELOPMENT of the Polaris missile and the FBM submarine is a triumph of sweat, faith and dedication over almost impossible odds.

The program had its beginnings in 1955, when the Army was building the Jupiter rocket and the Navy was instructed to devise a way to launch it from the sea.

Many experts were pessimistic about the Navy’s role in the missile age, and put their hopes in land based weapons. The gloomy outlook was based on the state of missile technology in the mid-fifties. Long-range rockets were all liquid fueled, since no solid fuel of sufficient thrust had been developed. Firing such a rocket involved elaborate fueling and aiming procedures, plus a lengthy countdown, and was a touchy business at best, even on land. At sea, in the confines of a ship, a mistake or accident with the volatile liquid fuel could spell disaster. Then too, it was difficult to determine the precise position of a ship at sea, and a one-degree error at the launch could cause an IRBM to miss its target by 30 miles at the termination of its flight.

That was the situation when, in 1955, the Secretary of the Navy created the Special Projects Office and named Rear Admiral William F. Raborn as its head. It was not an enviable job but the Admiral—and the Navy—believed the arguments in favor of a fleet ballistic missile out-weighed the problems.

Within a few weeks many of the best rocket and weapons specialists in the Navy were ordered to report to Washington, D. C. The project was under way.

THE FIRST MONTHs held few successes. The problem of safely handling liquid fuel aboard ship seemed more and more impossible and, to make matters worse, Jupiter itself proved too fragile for use at sea. The Navy, however, would not give up easily—if the Army rocket was unsuitable, the Navy would build its own.

Liquid fuels were out of the question. The Navy rocket would be compelled to use solid fuel, despite the fact that such a fuel did not yet exist. The problem was assigned to a group of Navy and industrial scientists while the rest of the program continued on the assumption the propellant would be forthcoming.

By late 1956 the Special Projects Office had developed a fuel powerful enough to lift the heavy nuclear warhead above the atmosphere—but slide rules revealed the rocket would be too large to carry aboard ship. Then came the second big break. A smaller, lighter warhead was made available by the Atomic Energy Commission and, consequently, the rocket could be reduced to a more reasonable size.

In the meantime, Special Projects engineers were running into other problems, the most stubborn of which was the guidance system. Successes, however, were beginning to outnumber the failures. For one thing, engineers had proved the new missile could be launched from a submerged submarine, a great advance over the surface launching system originally considered for the now defunct Navy Jupiter. Things were indeed looking up, and the Navy announced it would have a fleet ballistic missile deployed by 1963.

It was a deadline which shocked many of those familiar with weapons development. Designing and testing a new weapon may easily take a decade, and a concept as advanced as FBM could be expected to take even longer to produce.

THEN, IN 1957, the first Sputnik was fired into orbit from a launching pad in the Soviet Union. The development of the FBM had been an important program to the Navy for two years; now it was the top project spearheading the nation’s struggle for survival. On paper the system was clearly the most advanced and deadliest weapon in the world . . . but more than theory would be necessary if the U. S. was to retain her strong nuclear deterrent.

The 1963 deadline was discarded.

The date was now to be 1960.

Midnight oil burned in the Special Projects Offices. Admiral Raborn and his aides met with industrial executives. Red tape was cut, the navigation problem was solved, and the program forged ahead.

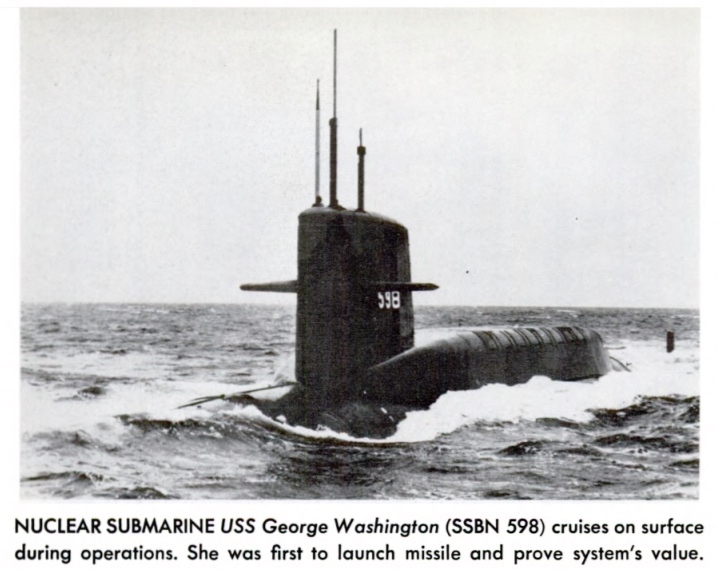

In January 1958, although the missile was yet to be manufactured, construction was begun on the first three FBM submarines. The first one, George Washington, had been laid down as the attack submarine Scorpion, but was cut in two and had a 130-foot weapon system section inserted. The first five SSBNs, the Washington class, were the result of this hurried redesigning. Uss Ethan Allen (SSBN 608), the sixth SSBN, was the first designed from the keel up as a Fleet Ballistic Missile sub.

THE MOST DRAMATIC moment in the development of Polaris took place on 20 Jul 1960, when the launching of a test missile from George Washington proved the workability of the POLARIS TEST MISSILE is launched system. This was the first time a Polaris was launched from a submerged submarine, and the successful launch was repeated less than three hours later.

On 15 Nov 1960 George Washington put to sea out of Charleston.

Several days later it was disclosed she was on station somewhere in the eastern Atlantic, carrying her 16 nuclear-tipped missiles. On that day atomic war was less likely than it had been for years.

During her first deployment, George Washington carried A-1 missiles. The A-1 Polaris, with a range of 1200 nautical miles, was an interim weapon, designed to be put on station in a hurry. It went to sea with the first five Polaris submarines.

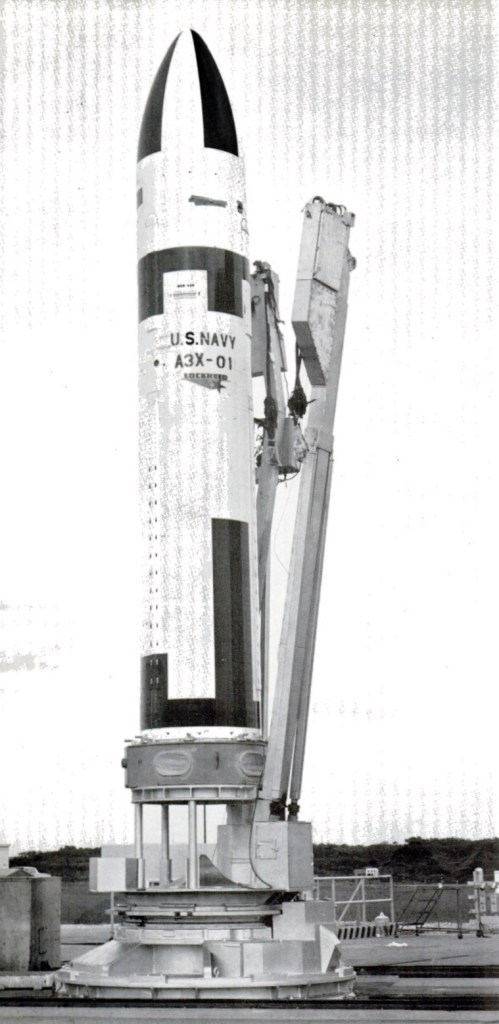

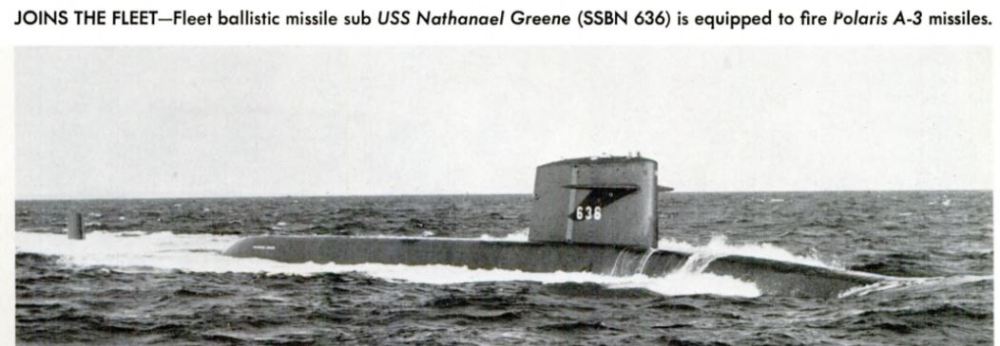

Later Polaris subs have carried the 1500 nautical mile A-2. Subs carrying A-2 rockets could remain submerged and strike anywhere on the earth, with the exception of a small triangular area in Eurasia. Today even that retreat is covered by the 2500 nautical mile (2880 statute mile) Polaris A-3. By 1967 41 FBM submarines will be operational, carrying a total of 756 missiles.

AT ANY TIME, upon orders from the President, these weapons could be released. Each missile would be forced from its tube by compressed air or, in later submarines the hot gas steam exhaust from a small rocket motor. After clearing the sub the first stage would ignite, driving Polaris into the upper atmosphere.

After one minute the primary stage would drop away and the second stage would fire for 70 seconds, making final corrections before it, too, disconnected from the warhead and dropped to earth.

The payload would continue upward under its own momentum. At a point some 500 miles above the surface of the earth it would flatten its trajectory and descend, like a meteor, toward its target. Thirty minutes after its launching the warhead would reach its destination and explode at a distance as much as 2880 miles from the submarine.

But Polaris is a deterrent, and the best part is—it works so well it may never have to be fired. Admiral Raborn has since retired, but the Special Projects Office continues to follow up on Polaris under the direction of Rear Admiral Ignatius J. (Pete) Galantin. The difficult part of the FBM program, however, lies in the past and the office has been given another project: implementing the deep sea exploration and engineering program outlined by the 1964 Stephen Report. But that’s another story. Watch for it.

Jon Franklin, JO1, USN

Are you going to Austin in August?

Not on the books yet. Depends on teaching schedule.

Mac

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History and commented:

I spent more time inside Missile Tubes on USS Michigan than I wanted to. My exposure to 63 millirems of ionizing radiation is mostly the result of those tube entries to remove guidance assemblies and/or be the reader.

It was interesting work. I wouldn’t trade it for anything…

#DaveLovesSubmarines

Obviously a different time. I was an FB on the Grant and made 6 patrols out of Guam on the Gold crew in the late 60’s. Never once did any of us ever go inside a tube or change a guidance assembly. Anything inside the tubes was done by MT’s. And to my knoweledge we never changed an assembly. I did spend my last year in a half at the Polaris Missile Facility in Bangor, WA. Testing guidance gimbal assemblies, man what a boring job.