I can almost hear the conversation on that morning when President Thomas Jefferson called Merriweather Lewis into his office and explained to him what he needed done.

“I need you to make your way from St. Louis to Oregon in the shortest possible time and distance.”

“What’s an “Oregon”, Thomas?”

“I’m not sure but I am fairly certain that you will know it when you find it. Discovering where it is will lead you right to the Pacific Ocean and the shortest route from here to there.”

And with that, Merriweather Lewis began a journey that would change the face of America.

The lands they would cross were known only to the natives who had roamed the plains and mountains for many millennia before Lewis and Clark sailed form Pittsburgh on the beginning of their trip. But the land had recently been purchased by the fledgling country and Jefferson was eager to have his men reach the Pacific Ocean by land as quickly as they could.

Depending on your point of view, it was either the greatest land journey in history or the very worst thing that could have happened to the vast unorganized lands that lay to the west of the river we called the Mississippi. The onslaught of men and women that would follow in the coming century changed the face of North America and the world forever.

The men who were exploders were great choices for the submarine that would bear their name.

Captain Lewis, with Drewyer and Shields, meeting the Shoshone Indians, August 13, 1805, on the headwaters of the Snake (Lembi) River, in Idaho. From a water color by C.M. Russell. Trail of Lewis and Clark 1804-1904

About the Ship’s Name:

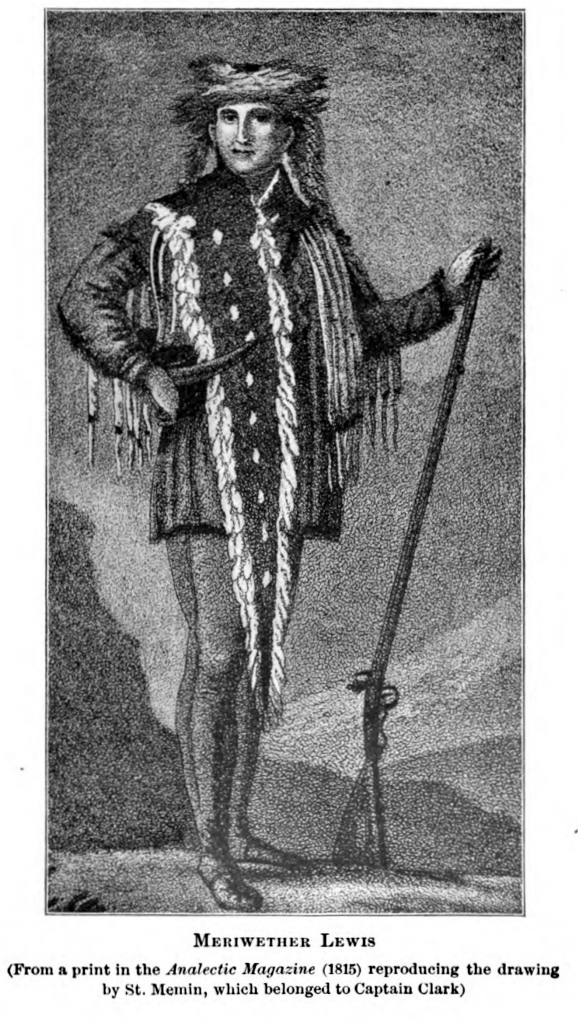

Meriwether Lewis was born 18 August 1774 in Albemarle County, Va. Much of his boyhood was spent learning the ways of wildlife and Indian lore. When he was 20 years old he was called to active duty during the “Whiskey Rebellion” in October 1794. After joining the Regular Army, he marched to Greenville, Ohio, the following year to view the signing of the Northwest Treaty. During this mission he was a subordinate of William Clark, his future companion in exploring the West.

Following Thomas Jefferson’s election, Lewis was offered the post of private secretary, and he became overseer of Jefferson’s domestic arrangements. In 1803, when Congress appropriated funds for exploring the West, Lewis went to Philadelphia to organize the expedition. As his companion officer he chose William Clark.

Clark was born 1 August 1770 in Caroline County, Va. Like Lewis, he was brought up in the revolutionary spirit and spent some of his early years defending against marauding Indians.

Designed to find a land route to the Pacific, the expedition mustered in Illinois in 1804 and for the next 28 months, proceeded to gain invaluable information about the unknown parts of the continent and its Indian inhabitants. The exploring party returned to St. Louis in September 1806.

For the rest of their lives, Lewis and Clark dedicated their abilities to administration of the U.S. territories and gave valuable service in Indian affairs. Meriwether Lewis died 11 October 1809 and William Clark died 1 September 1838.

Admiral Rickover’s recollection of Lewis and Clark’s expedition focused mainly on the difficulties of the journey and subsequent victory in reaching the Pacific Ocean.

USS LEWIS AND CLARK (SSBN 644)

NAMED FOR Meriwether Lewis (1774—1809) and William Clark (1770—1838), the Virginia-born captains under whose joint command a small American Army unit (three sergeants, 24 men, one Indian and two French Canadian interpreters) crossed from St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia River and back, thus completing one of the great transcontinental voyages of exploration, ranking in importance with those of Balboa (1513) and Mackenzie (1793).

Planned and personally supervised by President Jefferson, the expedition had as its objective the exploration of “the Mississippi River, and such principal streams of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean . . . may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent.” If such a water route could be found, much of the lucrative fur trade, then largely in Canadian hands, might be diverted to American seaports.

The President had long been interested in exploring this possibility; had, in fact, given aid to three previous attempts that came to nothing. He obtained from the Congress authorization and an initial grant of $2,500 in January 1803, a few months before the uncharted territory to be traversed by Lewis and Clark passed into our possession through the Louisiana Purchase. The expedition got underway, May 1804, in a bateau and two pirogues and did not return until nearly 21/2 years later. It is difficult for us to realize the importance of water transportation in those days. Men were inclined to believe certain navigable routes must exist simply because they so ardently wished for them. Thus, the hope of reaching the Orient by sailing westward was not relinquished even after it became known that the American land mass stood as a barrier between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans; this hope was merely transferred northward to the inland waterways of North America where for 300 years Spaniards, Frenchmen, and Englishmen diligently searched for the mythical Northwest Passage first postulated by Verrazano in 1524. To discover this passage was one of the avowed objects of the Hudson Bay Company.

Some envisaged it as a strait across Canada at the latitude of Hudson Bay, others as a “commingling of the headwaters” of major eastward and westward flowing rivers. Both versions of the myth were inscribed, as late as 1767, in Jonathan Carver’s map of America. Explorers kept the myth alive by asserting as fact what was pure fantasy. Thus, in 1765, Robert Rogers stated categorically that between the sources of the Missouri and the “Great River of the West” the portage was not above 30 miles. His River of the West was pure figment of the imagination but, oddly enough, speculation placed it near the actual location of the Columbia. No one then knew of the Rocky Mountains or imagined that such a barrier might divide America’s eastern and western rivers.

It must be counted a major gain of the Lewis and Clark Expedition that it laid to rest forever the myth of a navigable passage across the continent. It established, by actual observation that the sources of the Missouri and Columbia lay too far apart for an easy portage and that neither river was truly navigable in its~upper reaches. A feasible route from St. Louis to the Pacific was, indeed, mapped out, but 430 miles of it ran overland through rugged terrain, and the 3,555 miles by river were part way navigable by canoe only. Not until a century later did Amundsen find the only true Northwest Passage which does not, of course, bisect the continent but runs along Baffin Island through the Arctic Ocean. In 1960, the nuclear submarine Seadragon traversed the passage under water.

If then the Lewis and Clark Expedition could find no natural and easy cross-continental water route, it accomplished what in the end proved more important: It greatly strengthened our claim to the Oregon Territory, originally based on the discovery of the Columbia River in 1793 by Captain Robert Gray of the American ship Columbia Rediviva. Over the route mapped by Lewis and Clark soon came American trappers, and in 1811 Fort Astoria was built at the mouth of the Columbia, the first permanent settlement in the Oregon country.

America won the race to the Pacific by a hair’s breadth, for Canadian traders were fast approaching the coast. Mackenzie had traversed Canada from Lake Athabaska to the mouth of the Bella Coola as early as 1793, Simon Fraser came down the river named for him in 1808, and David Thompson followed part of the Lewis and Clark route in 1811. When he reached the mouth of the Columbia, he saw the American flag flying over Fort Astoria—it had been raised but a few months earlier!

As the historian John Bakeless writes: “Because of the Corps of Discovery, Oregon is American today. And ten white stars in the blue field of Old Glory stand for States of the Union that one by one grew up in the farms and mills, cities and homesteads, along the trail where weary men in tattered elk-skin cursed the rocks that tore their feet, sweated at the tow rope, poled against the savage current of the muddy Missouri, stumbled in the chilly streams of the Rockies, and staggered down the western end of the Lolo Trail.” It had been a hard journey and a long one. When Clark wrote in his diary, November 7, 1805, “Ocean in view! Oh Joy!” the weary explorers doubtless felt much the same triumph and relief as the men on the three small Spanish caravels when they heard the lookout on the Pinta cry “Tierra! Tierra!”

USS LEWIS AND CLARK was one of the BENJAMIN FRANKLIN – class nuclear powered fleet ballistic missile submarines. Generally similar to the LAFAYETTE – class, the twelve BENJAMIN FRANKLIN – class submarines had a quieter machinery design, and were thus considered a separate class. USS LEWIS AND CLARK was the first ship in the Navy to bear the name.

Both decommissioned and stricken from the Navy list on August 1, 1992, the LEWIS AND CLARK later entered the Navy’s Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Wash. Recycling was completed on September 23, 1996.

General Characteristics: Awarded: November 1, 1962

Keel laid: July 29, 1963

Launched: November 21, 1964

Commissioned: December 22, 1965

Decommissioned: August 1, 1992

Builder: Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., Newport News, Va.

Propulsion system: one S5W nuclear reactor

Propellers: one

Length: 425 feet (129.6 meters)

Beam: 33 feet (10 meters)

Draft: 31.5 feet (9.6 meters)

Displacement: Surfaced: approx. 7,250 tons; Submerged: approx. 8,250 tons

Speed: Surfaced: 16 – 20 knots; Submerged: 22 – 25 knots

Armament: 16 vertical tubes for Polaris or Poseidon missiles, four 21″ torpedo tubes for Mk-48 torpedoes, Mk-14/16 torpedoes, Mk-37 torpedoes and Mk-45 nuclear torpedoes

Crew: 13 Officers and 130 Enlisted (two crews)

After shakedown and missile firing off Cape Kennedy in 1966, Lewis and Clark joined the growing fleet of Polaris submarines silently patrolling the seas of the world for peace. In this great and grave mission she has quietly assumed her role in defending the country with the brave spirit of the explorers for whom she is named. She continued that work until she joined many of her sister boomers in retirement. Altogether, she served 27 years as an operational submarine.

Lewis and Clark’s sail and fairwater planes and the top of her rudder are on display at the Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum in Mt Pleasant, South Carolina, and is a part of a memorial to the officers and men of the U.S. Navy Submarine Service who served during the Cold War

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LA9N9jNpw30

Great information. Thank you for the time putting this together!

You are welcome. I really thought it might be useful to explain a little bit of what we did. SO many of our shipmates are gone now and the next generation just doesn’t know.

Mac