Chapter Seven: One fights a war where one is sent. (1916 – 1918)

“So, cheer up my son. Play the game. Take your medicine. Don’t squeal. Watch your step. After all, it is a splendid profession and an honorable career.” (Naval Institute Proceedings, XLI, No. 157 “Letters of a Retired Rear Admiral to his son” by Captain A. P. Niblack, U.S. Navy, 30 May 1913.)

From the Secretary of the Navy Annual Report: ANNAPOLIS COURT OF INQUIRY.

“At the close of the academic year a number of midshipmen at the Naval Academy were accused of having wrongfully obtained advance information in regard to certain examinations. As a result there was instituted a careful investigation into all the facts, this investigation culminating in a court of inquiry composed of officers in no way connected with or recently stationed at the institution. The report of the board was approved and carried out. Five midshipmen were dismissed, while a number of others were given lighter punishments, according to the degree of their connection with this unfortunate affair.

Sometime later there came to the attention of the authorities the fact that a number of cases of hazing had also occurred. The facts were carefully sifted, and the result was that six midshipmen were dismissed, a number of others being turned back or punished in such other ways as were deemed appropriate in each case. While the entire incident is to be regretted, it is felt that with the serious lesson that has been taught and with the various remedial steps that have been taken in consequence, the general situation has been greatly improved. Hazing has ended at Annapolis. Most of the young men there rejoice that its brutality no longer brings a stigma upon that great institution. If in the future there come to the Academy those who would revive it, they thereby invite the certainty of their immediate expulsion which now follows every act of hazing.”

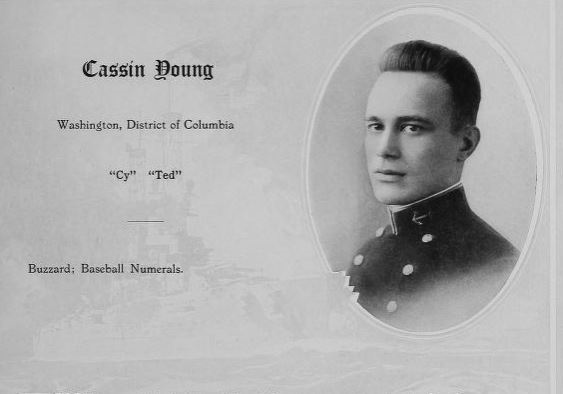

Cassin Young lost his father on January 5, 1905, long before he would find himself at the end of a four-year stint at the United States Naval Academy.

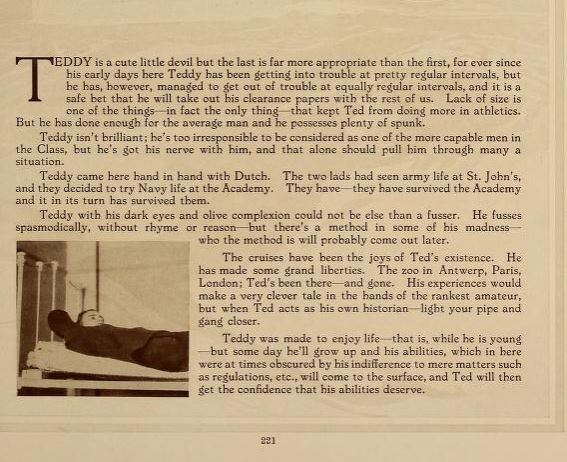

He was admitted as a Plebe from the great state of Wisconsin despite being born and spending much of his life in Washington DC. But the four years would bring him into contact with many young men who came from influential families and his life in the District probably exposed him to all of the trappings of power and politics. Of all the graduates, his name never appeared on the lists of accused for any of the major scandals. His log entry in the yearbook showed that he was no stranger to minor troubles though.

“Teddy has been getting into trouble at pretty regular intervals, but he has however managed to get out of trouble at equally regular intervals” is the surest sign that he had learned to play the game. For the rest of his career, only once would there ever be the hint of something that fell outside of the rules of that infamous “game” mentioned in the Niblack quote.

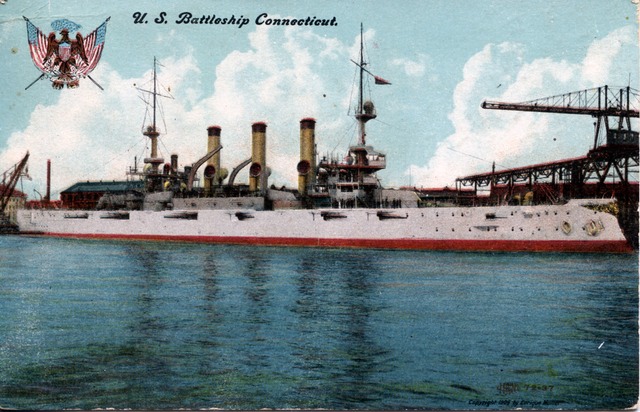

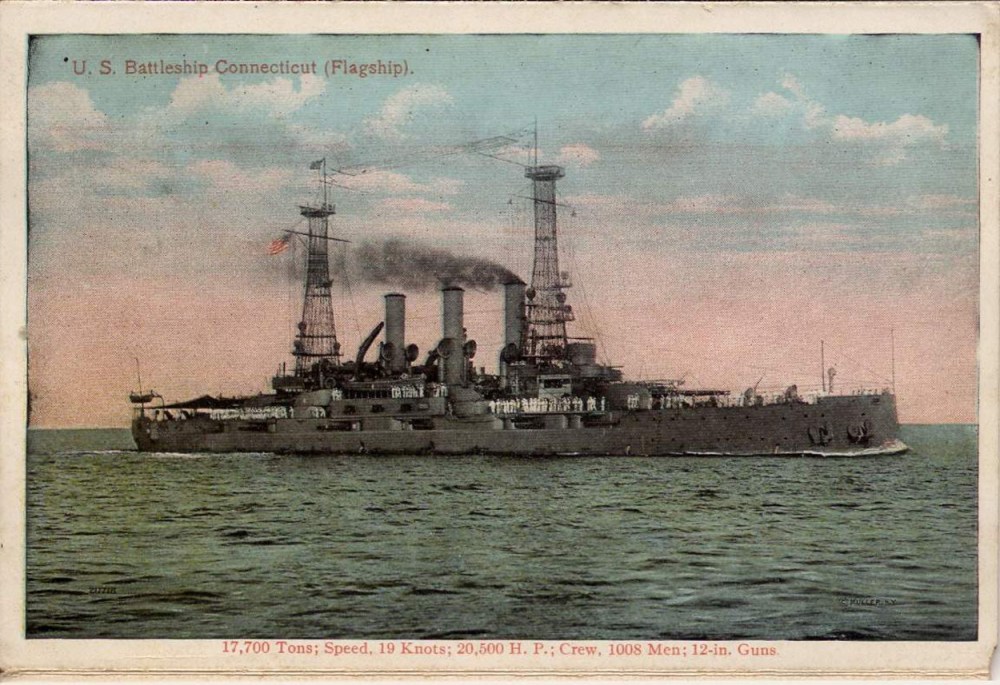

Meanwhile, upon graduation he found himself reporting to his very first official assignment, the newly recommissioned USS Connecticut BB -18.

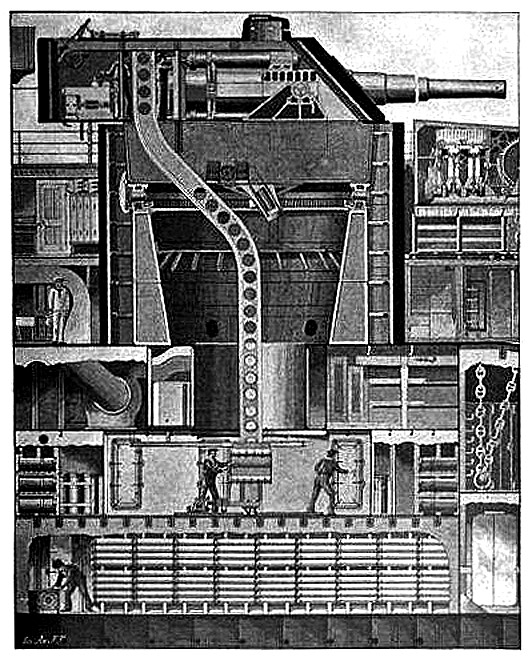

The Connecticut was laid down in March of 1903 and launched with great fanfare in front of thirty thousand people at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in September 1904. Her journeys included a ceremonial trip to commemorate the Landings at Jamestown Virginia and she was the flagship for President Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet that sailed around the world. This cruise demonstrated American power like it had never been shown before and demonstrated the advantages of completing the Panama Canal in easing the way that power could be moved from ocean to ocean more efficiently.

Connecticut had been placed in reserve in December 1915 as a cost saving measure. The early days of the European war had easily demonstrated that the real threat to the navies of the world was going to come this time from a new and dastardly weapon. Unrestricted submarine warfare. Prior to this war, ships at sea operated under certain codes with rules of engagement and humane treatment of non-military shipments and passenger lines. But Germany opened a new chapter in warfare by its use of this new technique and partially as a response to Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare, Connecticut was recommissioned on 3 October 1916. Two days later, Admiral Herbert O. Dunn made her the flagship of the Fifth Battleship Division, transferring his flag from the USS Minnesota. Connecticut acted as a shield against any belligerent attacks along the East Coast and in the Caribbean until the United States entered World War I on 6 April 1917.

Ensign Cassin Young was originally ordered to go to the USS Kansas, a sister ship of the Connecticut that was used as a training ship. On October 6, 1916, he along with seventeen of his fellow Ensigns (including W. W. Webb from Wisconsin), five Lieutenants, one Lieutenant Junior Grade and LCDR F.I. Oliver were all transferred to the newly recommissioned Connecticut for duty. The ship was still in the reserve fleet in Philadelphia and arrangements were made to bring the ship back to full service over the next few months. After fitting out the ship, they commenced operations using Virginia as their base. When war finally came, it was not the Connecticut’s fate to be an active part of the United States contribution to the Grand Fleet. Her age and her limitation of being coal powered made her a questionable choice for action in the new form of warfare being waged overseas.

The United States Navy’s overall contribution to the war in the beginning was limited. The British and German Fleets had already squared off and a decisive surface naval battle was not to be had. The scenarios where giant battleships in flying squadrons would decisively slug it out in close quarters had proved to be an illusion. On May 31, 1916, the weekend that Cassin Young and his classmates were enjoying their final days of Academy life and parties, the two giant fleets of the Royal Navy and Imperial Fleet were sailing into history near Jutland. This battle involved 250 ships, and over one hundred thousand men off the coast of Denmark’s in the North Sea. While statistically a draw in losses and significance militarily, the German High Sea Fleet had been driven back to its homeports and would put out to sea only three more times on minor sweeps. In response to this new dynamic, the Germans now turned to commerce raiding. The consequences for the rest of the war would be devastating for both sides but especially devastating for the ships that were unprepared for this new kind of warfare. But ships like the Connecticut were not what was needed. Despite the growing concerns from coastal communities for capital ships, smaller and faster anti-submarine vessels became the major focus for the country.

When Admiral Sims arrived in London, the British war planners were frank with him in revealing the threat. The rate of sinking at that time was nearly 900,000 tons of shipping per month, the total allied and neutral tonnage then being about 34,000,000 tons and the rate of new construction only about 177,000 tons per month. In other words, the Germans were sinking shipping faster than it could be built.

For the rest of the war, Connecticut was based in York River, Virginia. During that period, more than 1,000 trainees—midshipmen and gun crews for merchant ships—took part in exercises on her while she sailed in Chesapeake Bay and off the Virginia Capes. Despite her status at the beginning as being a modernized vessel, she was still dependent on one of the last vestiges of the Great White Fleet. Coal. In order to maintain her propulsion, she was reliant on a regular supply of coal to keep her moving forward. Additionally, she had very little defense against the modern submarines of the day. Testing secretly conducted by the Navy off the Virginia coast in 1915 had revealed that the armor found on Connecticut was not sufficient to withstand the direct attack of a modern submarine torpedo. The giant battleship class that was the backbone of the Navy was vulnerable to the sting of a wasp. In the years between 1915 and 1941, the Navy would not do enough in either design or tactics to counteract this threat with devastating consequences. It was a lesson that they would learn again and again during the ensuing war.

One of the mighty ships to emerge from the battleship building days before the war was the USS Arizona.

The Arizona was a super-dreadnaught ship of the Pennsylvania class that was designed for speed and power.

In an address at her launching, Secretary of the Navy Daniels stated, “The backbone of the navy still is the powerful dreadnaught that can keep the seas in any weather and which, with its great armament of powerful guns and secondary batteries, and with protection against submarine torpedo, can concentrate its power.” The Arizona was built in a remarkable fifteen months and was followed shortly after by the USS California, the first electrically driven battleship in the world which was also a thousand tons larger than the Arizona. Daniels also stated that the “Arizona could beat the Queen Elizabeth, the best ship in the British navy.” Like the Connecticut, the Arizona did not sail to join the war and spent the next few years patrolling the coast of America.

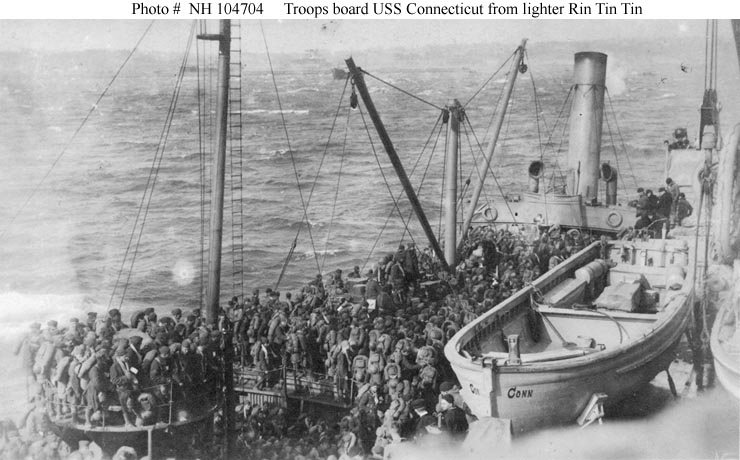

At the close of the war, the Connecticut and some of her sister ships like the Kansas were fitted out for transport duty, and between 6 January and 22 June 1919 made four voyages to return troops from France. On 23 June 1919, she was reassigned, becoming flagship of Battleship Squadron 2, Atlantic Fleet. Ensign Young would remain on board the ship until June of 1919 when he embarked on the next phase of his career. Like many other young officers, he would see the opportunities that lay ahead in the fledgling American submarine force. His future both in the Navy and in his personal life was about to radically change from the battleship navy that he had been a part of for most of his career up until then.