Chapter Six: The End and The Beginning

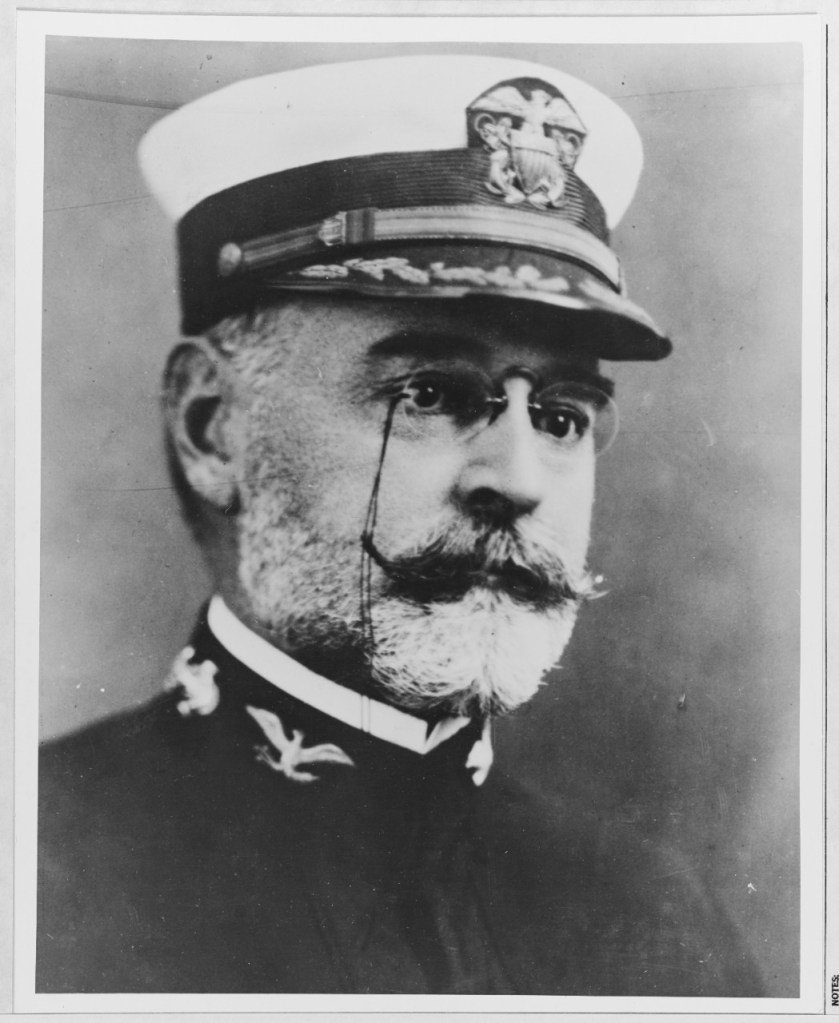

Josephus Daniels became the Secretary of the Navy after the election of Woodrow Wilson. He was a reformer in every sense of the word and brought with him very little understanding of the naval traditions that shaped the modern organization he inherited. He was determined to build the navy up, however and in his annual report, he noted the deficiency in planning for the future.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3018637&view=1up&seq=11&skin=2021

From his report to the President:

“In March, 1913, no doubt having in mind the failure of naval authorities and Congress to adopt a continuous policy, the General Board made this statement:

There is not now and there has never been in any true sense a governmental or departmental naval policy. The fleet as it exists is the growth of an inadequately expressed public opinion; and the growth has followed the law of expediency to meet temporary emergencies, and has had little or no relation to the true meaning of naval power, or to the Nation’s need therefor for the preservation of peace and for the support and advancement of our national policies. The Sixty-third Congress took long strides toward formulating a better naval policy, enacting long-desired legislation of the most serviceable character which will increase the efficiency and strength of the fleet. It opened new doors for promotion of officers and men.”

The 1915 Training Cruise

Young and his fellow midshipmen would find the summer training cruise of 1915 different from the previous cruises in many ways.

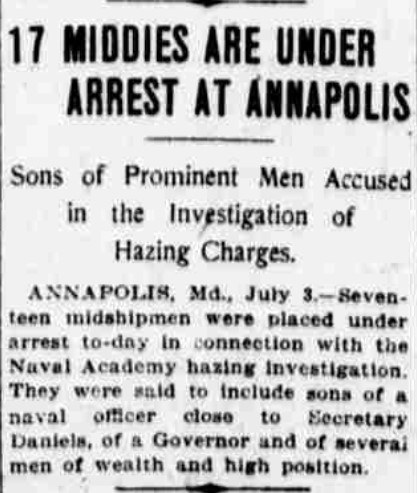

First of course was the unresolved scandal that involved cheating and hazing at the venerable old institute. The ships that sailed out of Annapolis carried most of the midshipmen after a delay of over a month related to the court of inquiry and investigations. Ships of that era used coal for propulsion but the black clouds of the boilers were not the only black clouds that followed the squadron. Sailing on a ship in the open sea brings a certain level of uncertainty but this level was heightened by the precarious situation involving many of their friends and colleagues.

Second, this cruise was unique because of its general direction. Instead of heading east to the beautiful old cities of Europe, it was headed south and west, away from any potential dangers from potential unfriendly attacks by submarines or unintentional encounters with undersea mines. Europe was beginning its second year of war and the papers were full of stories about attacks on the high seas by the belligerents. Interestingly enough, many people o influence in the US were working behind the scenes to prevent the US from becoming entangled in this “local” war. William Jennings Bryant, the former Secretary of State was working vigorously to build an isolationist movement to stop the US from assisting either side. He was as angry with the British for their evil blockade as he was with the Germans for using the deadly new submarine weapon.

Against this backdrop, the practice squadron sailed away from the Atlantic. For Cassin Young, this would be the first of many times he would see the Panama Canal. This miracle of technology was designed to strengthen American influence and power around the globe by shortening the distance ships needed to sail between the two major oceans. It had been built at great expense and sacrifice by the fledgling Americans as an instrument of global commerce but it was also built with the navy in mind. The series of locks and canals were dug to accommodate current and future planned dreadnaughts as well as the numerous cargo ships that would sail through her in the decades to come. Ship planners for years would reference the unique specifications of the canal as American was learning to accept that she would have to have a two-ocean policy.

From the Secretary of the Navy 1915 Annual Report

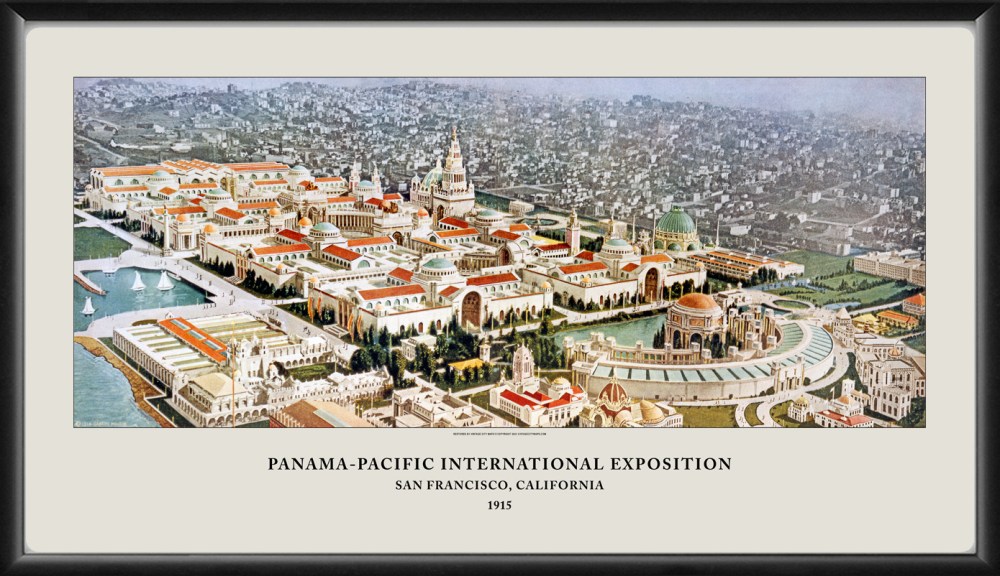

“During the Panama-Pacific Exposition the major portion of the Pacific Fleet was present for a good part of the time, the battleship Oregon being naturally the center of interest to all visitors at the exposition. In addition to these vessels, the Ohio, Missouri, and Wisconsin, carrying the midshipmen from the Naval Academy on the annual practice cruise, spent several weeks at the exposition. They were the first battleships to pass through the Panama Canal. The ease and dispatch with which the practice squadron was passed through the canal both going and returning afforded practical proof of the immense value of that important connecting link between the Atlantic and Pacific.”

Young and his comrades could not have been too aware but another purpose for this particular cruise was to demonstrate to the Japanese that America was not about to abandon the Pacific to a potential major power. Japan had shown in its earlier war with Russia that it could take on and defeat a major European power at sea and extend its influence beyond its borders. This power projection was not lost on political people in the United States. The early part of the 20th century is filled with stories about the “Yellow Peril” on both the west coast of the country and the Pacific islands such as Hawaii that might fall prey to an aggressive Japan in time of war. Japan had already flexed its muscle in the war as it aligned itself against Germany. The main goal was to gain control over German assets in the Pacific and the American naval presence was not yet strong enough to offer a counteracting force.

What the midshipmen did know however was that the cities of San Diego and San Francisco were lining up to welcome them with every manner of entertainment. The balls and receptions in each city were amazing affairs and the warm and welcoming weather of the west coast must have been a wonderful relief after the cold hard months in Maryland cooped up in small classrooms and lodging.

The training squadron arrived at San Diego on July 28th and Young got his first chance to see the west coast. He would have no way of knowing that many of his later assignments would bring him back here and provide he and his future family with a home in Coronado. For now, he and his fellows were all enjoying the moment as sailors on liberty in a very friendly Navy town. The only negative event of the cruise so far had been the loss of one of the propellers of the Ohio after leaving the Canal which delayed their arrival in San Diego. They would later sail to San Francisco, arriving on August 1st where they would be hosted by the city’s finest at a series of balls and events.

All of the darkness of the past few months were behind them as they were reminded that this was the real navy they would be serving upon graduation. The ships were a place where the midshipmen could feel the salt air of the Pacific stinging in their faces as the ships plowed through the waters and savor the exotic foods of California in many exciting new adventures.

But like all voyages, this one too came to an end.

The news of the end of the inquiries back at Annapolis came to the ships via wireless and copies of newspapers that followed every detail of the trials to the last days. The Court of Inquiry that was established by the naval secretary did not sustain the original sentences issued by Rear Admiral Fullam and in fact only two of the original seven were dismissed from the Academy. Moreover, the original young midshipman who had been accused was exonerated and the reminder of the accused issued demerits and smaller penalties. The Navy itself was judged as the principle offender in many ways and judged to be guilty of using the press and political power to suppress the truth. The accusations of course came from the politicians and powerful families. Many members of the Naval Academy staff were punished and dismissed for roles they played in the affair and as a final insult, Rear Admiral Fullam, the man who had been brought to the academy only a year before to conduct reforms, was informed by telegraph that he would be relieved immediately upon his return from the trip. His next assignment was to a remote command of insignificance in the Pacific Northwest.

The order to remove the Admiral was approved by President Wilson.

Interestingly enough, several of the key men who were openly involved with the trial were men of influence in Wilson’s party who were working very hard behind the scenes to help him achieve a second term in office. He had pledged before the first to only do one term but quickly found that it would not be enough time to institute all of his progressive reforms. The chief lawyer defending the midshipmen was a congressman from Virginia who took time out of the trial to coordinate Wilson’s ability to put aside his one term pledge and go on to win the next election cycle as President. The man who signed the orders to actually relieve Fullam and put an end to this affair was the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. His name was Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Cassin Young and the midshipmen returned to a decidedly different academy in September.

Captain Edward Walter Eberle had earned a captain’s commission on July 1, 1912. He attended the short course at the Naval War College in 1913; served as commander of Naval Gun Factory at Washington, D.C., and became Superintendent of the Naval Academy on September 1, 1915.

Young’s group was now the First Class but they were under a lot of scrutiny both academically and under the watchful eyes of the professionals who wanted no more ink wasted on internal issues. From September to June, there are little to no records in any newspapers about any ongoing issues with either issue. But Young’s class surely must have been aware of how tenuous their journey had been to date. They had survived the death of a classmate, a gambling infraction that could have ended may careers, and more recently a cheating and hazing scandal that tarnished anyone who was remotely close to its epicenter. But they had survived. Now, they were about to go out and join the fleet. Unlike the practice cruises made during their summers, this fleet was being prepared for a war that lay just beyond the horizon of the rising sun in the east.

Graduation had to have been a relief. Assignments from the Navy Department filtered in at first and then came as a flood. Some would go to the great battleships of the day. Some would find their lot on colliers and the newer destroyers that seemed to be gaining in importance. Nearly all would go to sea in one fashion or another.

Was it worth the trials? After all, they were about to be committed to several years of further deprivation and sacrifice in the name of gathering a reputation and a meager salary. Other men of their age had gone off to college or worked in business and would find their fortunes and freedoms much more improved than the men of the Academy.

The answer is not so simple. They had reached the end of one journey but were about to begin another. Some of them would find fortune and fame. Some would see their journey end up on the rocks and shoals. Walter W. Webb of Wisconsin would see himself gaining official recognition for “his initiative, good judgement, and seamanlike efforts shown in the salvaging of S.S. I’Ping after she had beached on the Yangtze River before Chungking”. Eleven years later then Commander Webb would find himself on the rocks along with the three ships he was charged with commanding as they grounded on the coast of Newfoundland. His story is but one of many from the Class of 1916.

But all of their stories bear truth to the letter written in Naval Institute Proceedings, XLI, No. 157 “Letters of a Retired Rear Admiral to his son” by Captain A. P. Niblack, U.S. Navy, 30 May 1913.

Observations and Reflections

“In the Navy, after you have been in it a certain number of years, everyone knows you, has you labeled, sized up and cataloged. If you have gotten into trouble, it is lovingly remembered and fixed to your name.”

“However, line officers of the Navy are the only class of people who have actually and continuously to demonstrate their fitness to hold their jobs, and the only ones who have to take a chance on being “smirched” after making good on all the requirements. Meanwhile from year to year the great uplift movement goes on, always new schemes to improve the efficiency of line officers, physical, mentally and morally. Examinations become more rigid. New tests are exacted. Inspections are made to test the efficiency of commanding officers, and every year the plucking knife sinks deeper and deeper.

“Meanwhile nobody else under the government has necessarily to know much of anything, except be geographically or politically well located. There is no examination for ambassador, collector of internal revenue, postmaster general, marshal, district attorney, interstate commerce commissioner, etc. It is merely a question of getting the appointment and being confirmed in the Senate.

“It is therefore some achievement, after all, to survive the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, and retire for age on attaining the age of 62 as a rear admiral, U.S. Navy.”

Those words written in 1913 span the ages for anyone who has since worn the uniform of a United States Naval officer.

The unfolding wars and global conflicts as Ensign Cassin Young and his classmates left the fabled hall on the River Severn would provide the backdrop for their unique journeys in their chosen profession.

One development from 1915 would later influence Ensign Young’s future. The recognition of the need for a more robust submarine community.

Josephus Daniels Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy – 1915

Especial attention has been given to the submarine question. The department has placed in command of the submarine flotilla an officer of high rank. A close study of the engine faults of these boats, which have long been so troublesome, is being made and all needed improvements are being energetically carried out. A shore base for these craft has been established at New London, where systematic work devoted to the training of submarine personnel and improvements in submarine mechanism may be carried forward with undivided effort.

Already much progress has been made. Other bases for submarines are to be established on both the Atlantic and Pacific. A study of the organization of the submarines disclosed the fact that 1,928 men on 14 mother ships were required for 29 submarines carrying 831 men. One mother can care for half a dozen children, but it was highly uneconomic to have so much mothering. It was decided to release a portion of these officers and men needed for other service and to establish submarine shore bases.

There was another reason besides the one of economy. It was that shore bases for submarines afford greater comfort for the men employed in this strenuous service. It has been found in foreign navies that after the strain and stress of a week’s run on a submarine the men needed the rest and relaxation on shore. This gave them fresh stimulus to return to the tests and fatiguing action required on a submarine.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3018637&view=1up&format=plaintext&seq=21&skin=2021