You never forget your first

There are few moments in any submariner’s life that equal the first time you submerge below the surface of the sea. For each generation or type of boat, the lead up to that dive is different. It might come at the end of a lengthy transit on the surface in one of many ports around the world. To be honest, if the transit was in rough seas, the relief that comes from being out of the rocking and rolling of the ocean may surpass the fear of the unknown. I did not want my fear to be known since it seemed that being a solid sailor included not showing fear.

But there was some fear. Despite the endless checks that were made on every potential problem prior to diving, you always had in the back of your mind that this was still a machine. Manned by men who while well trained, still were also capable of mistakes. Over the next few years, my trust would increase with each dive.

But the first dive on a new construction boat is different in my mind. While I was younger and operated on boats that had proven themselves many times, being a member of a new construction crew gave me a different perspective. While I greatly admire the builders at Newport News Shipbuilding, watching the building of this boat did occasionally cause me some concerns. Our role was often to observe and do fire watches as the builders moved about the hull installing new equipment. They own the boat until that special day when it is turned over and you could almost feel the stress of workers who were being pushed to finish on time.

One thing that was amazing to me is the number of times when a pipe or conduit needed to be moved around a previously installed air duct or other type of pipe. The usual discussion between the workers from the various shops was literally spiced with what I thought were exclusively sailor language. I learned over time that many of the shipyard workers were previous sailors, so that made sense. In the end, it all seemed to magically come together. With the addition of each new component, the seemingly spacious interior of the 688 we were building kept getting smaller and smaller.

When the day came for us to finally take the boat to sea, it was one crowded place. It was also the first time since I was a fireman that I had to sleep in the torpedo room. There were so many riders along, it still felt like we were tied up next to the pier packed with workers and observers.

Except we weren’t. We were about to go to sea for tests. And to be honest, this one made me more frightened than the first dive I had taken over seven years earlier. Inside of course. Not way would I let anyone see my concerns. I just prayed a little longer right before the dive point.

The dive of course was pretty normal. And I was too busy checking for leaks to notice anything unusual. It would be like that every time we dove after that. Just routine chaos followed by mostly silence. I miss that part.

But what about the first nuclear powered submarine? What was it like for them?

This article comes from just before they took Nautilus out for the first time. As I read it, I could actually feel myself on board the boat getting ready for her first dive.

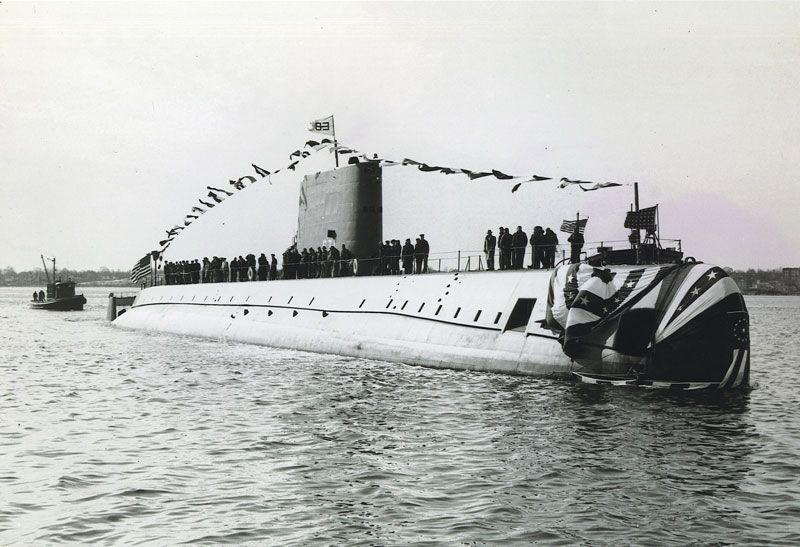

‘Fission Fleet’ Sailors Regain Sea Legs for Nautilus Trials

THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. July 5 1954

By Elton C. Fay

Associated Press Staff Writer

This country’s first fission fleet sailors are polishing off the training they need to operate the world’s first atomic submarine.

They’ve been dry land sailors for almost three years, but the time Is Approaching when they will take the U. 8. 8. Nautilus on the first critical trial of a long series of tests.

During much of the last three years, the men have lived and worked on an arid plain in Idaho, while they helped to build and learned to operate the original, land-based prototype of the nuclear power plant that will drive the Nautilus.

So, with their skipper, Comdr. Eugene P. Wilkinson of Long Beach, Calif., they are taking a refresher course in seamanship as well as practicing up for operating a vessel unlike anything that has sailed before.

Training Device Used.

At the Navy’s New London, Conn., submarine base the crew trains daily either in boats operating out of the base or in an amazing piece of machinery called the “Askania device.” The Askania device is to the submarine service what the Link trainer is to airmen. While firmly grounded, it contains all the controls and simulates all the conditions of a submarine operating at sea.

The Nautilus’ testing begins even before the crew casts off the lines and she moves out for the first time under her own, unique power from the fitting-out dock of the Electric Boat Division of General Dynamics Corp. at Groton, Conn.

Using compressed air supplied from dockside high-pressure lines, the men are trying out every tank, pipe, conduit and compartment in the huge hull. Soap, applied to all fittings and seals, shows the tiniest bubble of air that could cause trouble later.

The vessel’s controls and indicator system—including the “Christmas tree” board of red and green lights to show whether innumerable valves are closed or open—will be checked out thoroughly.

Trials May Start in Summer.

Then the Nautilus Will be ready for the big day, probably sometime later this summer or early fall, when she heads down the Thames River for Long Island Sound, where the initial trials will be run.

Aboard her at different times during the weeks of trials will be high officials and the men who supervised and helped build the Nautilus—among them Admiral Carney, chief of naval operations, and Rear Admiral H. G. Rickover, who has headed the nuclear ship propulsion project since the atomic submarine program got under way more than three years ago.

Customarily, a naval vessel built under contract in a private yard Is operated in the initial trials by civilian crews of the builder. The Nautilus is different. Only the men who grew up with her design and building, the crew trained at the Eastern Idaho test plant of the Atomic Energy Commission and the yards of Electric Boat while the submarine was building, know how to handle her.

When the Nautilus puts out for the diving tests her skipper will know the precise total dis-placement, almost to the ounce, of his ship. Everything that has been put aboard her, down to the smallest item of supply, has been weighed.

The Nautilus’ first dive presumably won’t be the spectacular, “take her down” type of swift glide beneath the surface seen in the movie thrillers of undersea warfare. Instead, the Nautilus will be stopped dead in the water, floating motionless.

Flood Down Slowly.

Then the hydraulic control men. will flood her down slowly, opening and closing vents in the ballast tanks in short, quick bursts to prevent a sudden in-surge of water, slowly, carefully, the point will be reached where the atomic submarine has only a tiny fraction of “positive” buoyancy, just enough so she floats with deck awash.

The bow diving plane will be angled down slightly. The skip-per will kick her ahead slowly by cracking steam cautiously into the turbine, aiming to take her down at an easy angle and a speed of perhaps only four or five knots (enough to keep steerageway.) For a long time, presumably several days, she will cruise slowly at shallow depth.

With and if the Nautilus proves out to the satisfaction of all her technical and operating hands, she will put out to the open sea for the deep dive trials. Only then will the Navy know definitely whether she will fulfill the specifications for a submarine that can travel deeper, farther and faster under water than any submersible ever built.

Sea Trials for Nautilus would not come until January 1955

What a great trip down memory lane. As I write these blogs, I am reminded about how significant the progress was made to get us to where we are today. I’m also reminded how few of the men involved are probably still with us. Losing my good friend Al Marshall who was the first skipper of the San Francisco has made me more aware of how precious life is and how fast it goes. But I am grateful for having known him and learned from him. You see, what makes the Navy in general and submarines in particular so impactful are the brave men and women who operate them while balancing fear with courage on every dive.

You see, I was in the control room when we made that first dive. Admiral Rickover was there too for one of his last dives. The Navy finally forced his retirement not long after that dive. And Commander Al Marshall was there too. Nothing about his presence displayed anything but absolute confidence in his boat and crew. That gave me a needed sense of assurance. And I wasn’t going to shame him with anything less but the same confidence.

I miss you, old friend. I am glad God gave you peace. I will see you again.

Mister Mac

Like every submariner, my first dive was exhilarating, but to me, since everyone around me was taking it like “business as usual”, it has just faded into one of the countless dives since then (either that, or it was sensory overload and I just can’t recall the specifics). However, there is one dive that sticks out like no other in my memory. We had just completed a three month mini-overhaul in the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in preparation to deploy on West Pac. They had cut a hole in the side of the boat that you could drive a truck through. I had my own assigned space to check on that dive, but when I finished my area I headed straight for that hull cut so I could put my own hands on it (they would not put insulation over it until after the sea trials were over). When I took my hand off of the hull and turned around I found the Engineer looking over my shoulder. “What’s the matter Maxey… don’t you trust the shipyard?”, he asked. “Not for one damn minute” I replied. “Well I already checked it myself not 5 minutes ago, so don’t you trust me?” “Not for one damn minute” I said again. “Good man”, he said…. “And if it’s any consolation, the yardbird that made the weld, and the one did the radiography, and the one that checked the radiography are all underway with us, so if we go down, those sons of b*%#&’s go down with us”. Somehow, I felt a bit better.

ICFTBMT1(SS) Maxey, USN (retired)

Thanks for your service and thanks for a great response. I spent a bit of time in Mare Island myself and double checked everyone’s work no matter how well I thought they did.

Mac

I’ve never served, but was privileged enough to have done a day cruise on the USS MAINE in 1998. I was in the crew’s mess getting a cup of coffee (I had rushed to Norfolk the previous night from West Virginia, because I wasn’t going to miss a chance to sail on a submarine) when the boat submerged. I was looking up at the ceiling of the passageway when the COB saw me and asked what I was doing. I told him I was thinking about going out on deck when the realization hit that we were underwater. Then I said “Wow!” out loud and the COB just smiled.. As my first time being on a submarine at sea and submerging… the wonderment of what I was doing, where I was, etc., finally hit me (and that feeling hasn’t diminished over the course of the 26 years that has passed since that day.)

Jim

The evolution on a Trident is a lot smoother than that of one of the older boats. There were times at sea on Ohio that I forgot I was at sea. Interestingly enough, I felt the sea a lot more when I rode the Nimitz for a mission where I delivered some training to the crew. It was my first time on a surface ship, and I had assumed that her size would make the rock and roll easier to take. A few years later, I got a real taste of bad weather when the tender I was on was surged out of Norfolk to avoid a bad storm. We were about 3/4 low on fuel which made the trip horrendous. I never saw so many sick kids at one time in my life than down in my enginerooms. And no, I didn’t get seasick either time