(NOTE: This post is a big longer than my usual post, but hopefully it will be worth your time to read.)

Nuclear Power: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

I was reading about the two nuclear powered aircraft carriers and their battle groups gathering in the eastern Mediterranean this week and got to thinking about when I was a young boy. I used to build model ships, planes and other reproductions. My basement growing up was home to fleets of PT boats, destroyers, battleships, submarines and aircraft of every kind. I am pretty sure I spent every dime I ever made during those days supporting my hobby.

Some of the biggest kinds were the various aircraft carriers available. The biggest, by far, was the replica of the USS Enterprise. We would spend many hours building them then many more staging them for mock attacks in fictional wars.

The Enterprise was the most fascinating since it had all of the aircraft that would later serve in the Vietnam War. The numbers of men who would be required to operate the real ship must have been staggering but one thing was very clear. She could sail for years without having to stop for fuel. Her contemporary nuclear escorts ships were also among my favorites.

My other hobby besides building model ships was reading about the Second World War in the Pacific. I understood that the big ships didn’t just magically show up half an ocean away without some kind of supply chain. The War in the Pacific was won by brave men who had fast ships and planes but all of those required an uninterrupted supply of energy to move forward. The Japanese came to understand that as the American and allied ships, submarines and planes slowly cut their supply lines to pieces.

It’s really hard for me to understand how time has advanced so quickly.

Here we are in 2023, sixty years past the pivotal year of 1963 when decisions were still being made about the types of ships and submarines that would have so much influence in the years since then. To get a real flavor for the crossroads the country was facing, all you have to do is read the congressional records that were recorded during that year.

Vietnam was still a far-away skirmish and the Cold War was the true existential threat (with apologies to those who believe that climate change somehow is today). By 1963, many modern nuclear submarines and a handful of nuclear powered surface ships were already proving the value of this unique form of propulsion power. The Navy was still operating with many oil powered ships left over from the Second World War but they were rapidly running out of shell life. It’s hard to imagine it now, but a good percentage of the fleet in 1963 was built in 1943-1946 which would make their age about 20 years at that time. Many had been modernized with advanced weapons systems but all of the war veterans had many miles under their keeps and nearly all required vast amounts of fuel and maintenance.

So it was that Congress needed to decide which types of ships to build and finance to face the future threats. We still ar esubject to their decisions today.

The first part of the discussion was a wide ranging discussion on all kinds of logistics questions. Then VADML H G Rickover was brought in to discuss the two most critical questions. The first question was about surface powered nuclear ships. The second question was about the loss of one of the Navy’s newest and most advanced submarines in April of that year. The shocking loss of the USS Thresher was the first nuclear powered submarine accident and its timing was smack in the middle of one of the largest expansions of nuclear powered submarines in the history of the world.

Here is the story in three parts.

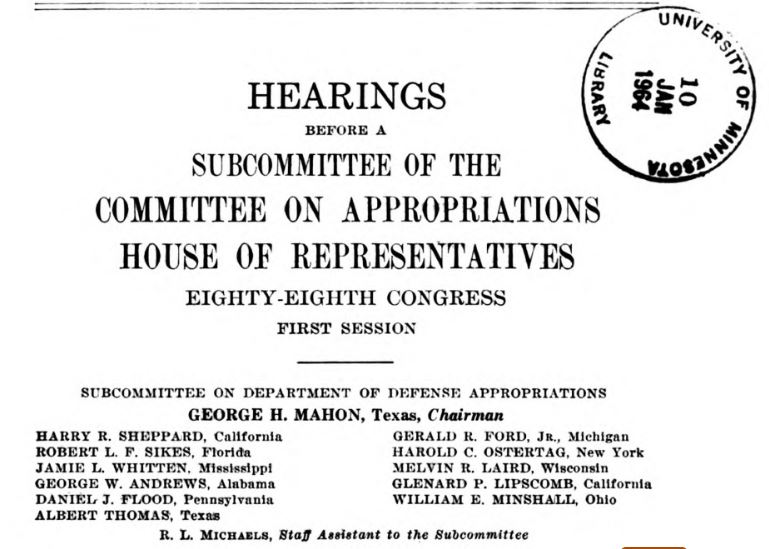

Department of Defense appropriations for 1964; statement of Hyman G. Rickover, contracting procedures, nuclear powered navy. Hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives, Eighty-eighth Congress, first session. There are a few really familiar names that someday would become familiar for many different reasons. I will highlight a few of them in read in the article.

HYMAN G. RICKOVER, VICE ADMIRAL, U.S. NAVY, MANAGER,

NAVAL REACTORS, U.S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION

PART ONE: NUCLEAR NAVY PROPOSALS

Now, will you give us your idea as to the nuclear Navy?

It has been suggested that perhaps all ships over a certain tonnage should be nuclear powered. What is the latest thinking, and what is your latest thinking on this question?

Admiral RICKOVER: There has been considerable discussion over many years as to what extent the Navy should go nuclear powered. As far as the submarines are concerned, a clean – cut decision was made several years ago and all submarines authorized for quite some years have all been nuclear powered. That is the policy of the Navy Department.

Mr. LAIRD: Up until this year?

(Melvin R. Laird from Wisconsin was a congressman that supported a strong defense posture and had sometimes been critical of Secretary McNamara. In September 1966, characterizing himself as a member of the loyal opposition, he publicly charged the Johnson administration with deception about Vietnam war costs and for delaying decisions to escalate the ground war until after the 1966 congressional elections. Laird also criticized McNamara’s management and decision-making practices. He would later serve under Richard Nixon as the Secretary of Defense. He was most well-known for his coining of the term Vietnamization which described the ill-fated attempt to turn over all defense activities in Vietnam as the Americans withdrew).

Admiral RICKOVER: Not on submarines, sir

Mr. LAIRD: In the 5 – year program submitted by the Secretary, there has been a new policy established of conversion of present conventional powered submarines instead of maintaining last year’s program of construction of new nuclear subs. This, I believe, is a mistake and developed a record supporting my position when Secretary McNamara appeared before this committee.

Admiral RICKOVER: For submarines, I am not aware of any new policy. Of course, the current policy to build only nuclear – powered combat submarines does not preclude building prototype models of other types of submarines for testing new developments.

I would like to add here, it is not my job to decide whether a ship should or should not be nuclear powered. However, I have very definite ideas.

Take an aircraft carrier. It is not my job to recommend whether we should have aircraft carriers, or how many we should have. That is the function of the operating people in the Navy Department. I do claim that for certain types of ships, if we are going to build them, we would be better off if we make them nuclear powered, and that is as far as I can go. I can only render a technical recommendation on the type of propulsion we should have; not an operating judgment on the types of warships we should build.

Mr. MAHON: What do you think we probably should do as Members of Congress toward encouraging the Navy to change its determination with respect to the carrier which we most recently financed so as to provide that it be made nuclear powered rather than conventionally powered, as has been previously determined by the executive and the legislative branch

Admiral RICKOVER: May I answer this question by going back to your previous question? I want to answer your questions concerning surface ships. I have covered the submarine part, I believe. I said there had been a great deal of discussion whether we should also go to nuclear power in the surface ship Navy.

Two years ago the House Armed Services Committee recommended as a result of hearings, that all combatant surface ships over 8,000 tons should be nuclear-powered. The Navy at that time was conducting a study and came to the conclusion that over a 20 – year life of a surface ship, by including construction as well as operating costs a nuclear ship would cost roughly 1.3 to 1.5 times as much as a conventional ship. Additional studies have been made over the last 2 years as we have gained experience through the construction and operation of our first nuclear surface ships. Last winter another study was made by the Navy. This study came about because of the experience gained in the initial operation of the aircraft carrier Enterprise, the guided missile cruiser Long Beach, and the guided missile frigate Bainbridge and because of the increase in reactor power and core life of nuclear plants being developed by the Atomic Energy Commission. The immediate purpose of this study was to determine whether the conventionally powered aircraft carrier authorized in last year’s appropriation should be changed to nuclear propulsion.

The Navy came to the conclusion there was a differential of only about 20 percent in investment operating and maintenance cost for a new four – reactor aircraft carrier over a 20 – year period compared to a conventional aircraft carrier instead of 30 to 50 percent. The cost increase for nuclear propulsion does not include any allowance for the reduction in the cost of replenishment of the fleet that would be brought about by the elimination of the need for fuel oil in the nuclear ships. Based on the results of this study and the improved characteristics which can now be incorporated in a four – reactor aircraft carrier the Secretary of the Navy last January recommended to the Secretary of Defense that the fiscal year 1963 aircraft carrier which you had appropriated for as conventionally powered be changed to nuclear propulsion

When this came to the Secretary of Defense, he decided he wanted additional information so he caused additional studies to be made. These studies are currently going on.

I think these studies will get into other features besides the particular carrier. I believe the Secretary of Defense has decided to withhold a decision until he gets the study results which as far as I know, may encompass the composition of the surface Navy. That is where the matter stands now.

You asked, what can Congress do? I think what you can do to augment, to hasten the use of nuclear power, is to recognize that we are not going to make progress unless we build something. As long as we keep it in our minds and on the drawing boards, we cannot make the improvements that can come only through manufacturing and operating this equipment. We have found that the only way we can cut costs and make real improvements in our propulsion plants is by actually building them.

For example, we built the Enterprise. It was undoubtedly a costly ship. But we learned a great deal from the Enterprise. We learned how to design a plant with four reactors that can power an aircraft carrier the size of Enterprise instead of eight reactors, but we would not have learned how to design the four higher powered reactors if we had not built the eight – reactor plant.

Through our experience we have also learned how to design and build reactor cores that will last more than twice as long as those now in Enterprise even though they must also operate at about twice the power. We can do this. But until we actually start building more plants and more ships, we cannot continue making advances. The Long Beach, Enterprise, and Bainbridge were authorized in fiscal years 1957, 1958, and 1959. In the ensuing 5 years only two more nuclear surface warships have been authorized by Congress. One of these, the nuclear frigate in the 1963 program has now been deferred for 2 years because the new weapons system planned for this ship is not yet developed, and the funds have been assigned to other programs.

Mr. FLOOD: With reference to the tonnage, and to identify a class so I understand, on the 8,000 tons as the minimum for nuclear, what would be the class ship?

Admiral RICKOVER: A frigate or a large destroyer, depending on the armament that is put on the ship. The Bainbridge which carries TERRIER missiles, is a frigate. Admiral Hayward, who until a few days ago was fleet commander of the Enterprise and Bainbridge in the Mediterranean, has a glowing account of the performance of these ships as compared with similar conventionally powered ships. In fact the Bainbridge has been operating so well that he is recommending omission of the yard overhaul required for a new ship shortly after she leaves her building yard The Bainbridge does not need any such overhaul, she is operating so well.

Mr. FORD: What is the tonnage of the Bainbridge?

(Congressman Gerald R. Ford, former US Navy Officer in World War 2 and future one term President of the United States. The aircraft carrier Gerald R. Ford CVN – 78 was named after him.)

Admiral RICKOVER: About 9,000 tons sir.

Another aspect about nuclear – powered ships is that we believe we can keep them out of Navy yards for a longer period of time and this we are now doing.

On submarines when we started the time between overhaul periods was 18 months That has now been increased to about 3 years I have recommended 5 – year intervals between submarine overhauls and I believe the same may be done for nuclear surface ships

Mr. FLOOD: Five years

Admiral RICKOVER: Yes sir. I have recommended that the interval between overhauls for sub marines except for something unusual be 5 years

Mr. FLOOD: Can you not do that under your cost differentials?

Admiral RICKOVER: I am a prejudiced witness. When you are building a weapon of war you cannot set down a specific figure that one is 20 percent cheaper than another especially when you are trying to look into the future to determine relative costs 15 to 20 years from now. For the very short time in its life that it may perform under real war conditions its only purpose for existence the significant question becomes, will it do the best job?

Mr. FLOOD: A witness can never establish his own prejudice. We will decide that.

Admiral RICKOVER. I know what goes on in my mind better than you do Mr. Flood. I am an expert personal thinker. I am prejudiced sir.

(I can imagine the Admiral lecturing the Congressman on this fine point… anyone who ever met him can hear his voice and the strength in it)

PART TWO: “THRESHER”SUBMARINE DISASTER

Mr. MAHON: Admiral the country was shocked by the loss of the Thresher. We have lost submarines before and we have lost other types of ships before and we will lose ships in the future but the loss of the Thresher does raise questions as to the safety of the submarine fleet.

Will you comment on the Thresher Generally?

Admiral RICKOVER: I have to do this very generally I have testified before the Thresher court of inquiry which is still in session and I may not divulge my testimony.

Mr. MAHON: We do not wish you to do that. Tell us what you think regardless

Admiral RICKOVER: I am trying to see how I can answer your question.

In the first place a submarine is probably the most complicated weapon particularly a nuclear – powered submarine that has ever existed. It has millions of parts. There is an essential difference between a warship and an airplane or a missile. An airplane is expendable after a few years. A missile is also quickly expendable. A submarine is not. It must last a minimum of 20 years. This gives us a serious problem in design construction and operation.

Naturally when you have so many items in a ship there is a great deal of chance for poor design or workmanship. I think what will probably come out of the Thresher disaster is some change in the way the Navy designs constructs and operates submarines.

I would like to look on the Thresher as a providential warning rather than a means of assigning blame to anyone. Everyone concerned was well intentioned If we look at it as a means for learning how to do better, then the loss of the Thresher will have served a useful purpose I only hope we do learn the true lessons.

There have been other submarine casualties where we have not learned the true lesson. We have not taken full advantage of them. Our society must find a way of benefiting from mistakes and not glossing over them because we are afraid of hurting the feelings of people.

The loss of the Thresher and her crew is too important to permit personal considerations to enter. I hope we can eke out all the lessons we can.

Mr. MAHON: Do you think we will ever find the Thresher?

Admiral RICKOVER: It may be possible to find her. To raise her would be obviously a very difficult thing

I get many letters from people particularly from schoolchildren with suggestions on how to raise the Thresher. The suggestions generally divide themselves into two basic types; one we call the ice-tong method — to lower a large ice tong and raise her; the other is the horse shoe magnet approach.

Many of the children who are quite interested and probably encouraged by their schoolteachers have offered to give us the idea free

Mr. MAHON: You have to find her first

Admiral RICKOVER: If she is not buried in silt it may be possible to find her. The Navy has already taken some pictures of the bottom which show debris which may or may not be from the Thresher.

We do have means of taking pictures of the bottom. I have seen some of the pictures. The Thresher may have gone down at a high rate of speed and become embedded in silt.

Mr. FLOOD: Was there an implosion or an explosion?

Admiral RICKOVER: I consider there was little or no possibility of there having been a nuclear accident because the reactor is so designed as to prevent this. Furthermore with the type of reactor construction we use, the reactors are impervious to sea water. We have had no evidence of any release of radioactivity from the Thresher.

Mr. MINSHALL: I do not believe he understood the question by Mr. Flood.

Admiral RICKOVER I do not know what caused the accident to the Thresher. One theory is that a leak developed in the ship which admitted considerable quantities of salt water and caused her to sink. This is what one would gather from the last cryptic words reported in the newspapers. I am not telling you anything here that is not public knowledge

Mr. SHEPPARD: Was it sunk by an external force?

Admiral RICKOVER: I do not believe so. My personal opinion is that a leak developed inside the ship that admitted water faster than the ship could cope with and the ship sank.

Mr. LAIRD: Last year Admiral you went into some detail in your presentation before us on the personnel problem. I wonder if we could have some comments on that later this year off the record.

Admiral RICKOVER I do not object to putting this on the record.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951p00793213g&seq=23

The question of the Thresher remains something that is still being studied. But in 1963, the country was still grappling with the loss of the ship and crew. Had technology raced to far ahead for reasonable men to react to tragedy?

Part Three: Finding the Thresher

From the book “Mud, muscle, and miracles: marine salvage in the United States Navy” / C.A. Bartholomew

“The nuclear attack submarine Thresher sank in 8,400 feet of water off the New England coast during trials following her post-shakedown availability on 10 April 1963. At the time she went down, the Navy had no organization, no search techniques, and no specific procedures for mounting a deep-ocean search and identification operation. The response to the casualty, however, was immediate. Within a few hours, a full – scale search effort with thirteen ships had been laid on to seek any signs of life from Thresher. After some twenty hours, all hope of finding survivors had passed. The operation changed from a search and rescue operation to an ad hoc oceanographic effort under Captain Frank A. Andrews to locate the wreck of the submarine. The Navy had an intense interest in deter- mining the cause of the loss for the same reasons it had had in the loss of F – 4 nearly fifty years before. If the cause of the disaster could be identified, it could be eliminated in other submarines.

As with all deep – ocean operations, the first step was to find the lost object. Designated as the search area was a square, 10 miles on a side and centered on the position of Thresher’s escort, Skylark :ASR 20 ), when contact had been lost. The search team consisted of three elements:

The first part of the team was the sea element, designated Task Force 89.7. This element constantly changed in the number and types of ships depending on the specific task in progress. Captain Andrews commanded the sea element.

The second element was an eleven – man, shore – based brain trust, the CNO Technical Advisory Group, that provided technical guidance and a myriad of other services to support the at – sea effort. Dr. Arthur Maxwell, senior oceanographer from the Office of Naval Research, and Captain Charles B. Bishop chaired this group.

The third element was the Thresher Advisory Group set up at Wood’s Hole Oceanographic Institution under Mr. Arthur Molloy of the Navy’s Oceanographic Office in Suitland, Maryland. This group analyzed all data obtained at sea and prepared search charts. It also performed the necessary work of briefing senior naval officers and the officers of ships joining the search operation.

Just three days after the loss of the submarine, the initial plan for locating Thresher was formulated in a conference aboard the Wood’s Hole oceanographic research ship Atlantis II. This conference included a lengthy radio telephone conversation with Dr. Brackett Hersey, chief physical oceanographer at Wood’s Hole, who confirmed the basic plan’s consistency with the thinking prevalent in the oceanographic community.

There were four phases to the plan. First, sonic depth – finding sweeps would cover the entire 100 – square – mile area in sweeps 300 yards wide. Second, all contacts classified as “possible “would be investigated with deep – towed Geiger counters, side – scan sonars, or magnetometers. Third, all contacts remaining after the first two phases would be photographed with either a deep – sea television camera or a still camera. Finally, photographed wreckage would be examined visually from the bathyscaph Trieste.

This imaginative overall plan had a high degree of logic, but there were a few problems. No one knew for sure if the hull of Thresher would return an echo from the search fathometer. Some thought the hull would be buried; others suggested it had broken up. Nor did anyone know if navigation of the disaster area could be carried out accurately enough to ensure complete coverage. No one had any real experience at towing the various search sensors near the bottom at great depth or in placing camera for precise deep photography. It looked like a tough job. It would be.

The search started in accordance with the plan. However, it soon became apparent that because of unpredictable surface currents that forced relatively imprecise navigation, the search would be coarse. Overcoming the problems called for the cluster technique. With this technique, all echoes reported by survey ships are plotted; then a second, third, and even a fourth ship goes into the same area and their echoes are plotted. When a cluster of contacts develop in a small area, it is considered worthy of further investigation.

Twelve positions were defined in this way. As the operation continued, search techniques were refined by better navigation. Unfortunately, with the improvements the twelve positions grew to ninety, many suspected to be bottom topography. Side – scan sonars, cameras, and magnetometers produced no beneficial results, because the towing surface ship had no idea of the position of the sensor on its 9,000 – foot towline.

The break that made the difference came on 14 May. Atlantis II, working around a high – probability contact designated “Delta, “obtained photographs of some very suspicious debris – paper, wire, and twisted metal. The search concentrated on a 2 – by – 2 mile square – one twenty – fifth of the original search area – centered on Delta. By 15 June debris that obviously came from Thresher had been identified. It was time to call in Trieste.

With Fort Snelling (LSD 30) as a support base and Preserver as an assist vessel, Trieste made ten dives under the command of Lieutenant Commander Don Keach with Lieutenant John B. Mooney, Jr., as copilot. On 6 September the bathyscaph found a large portion of Thresher’s wreckage and a debris field that Keach characterized as a huge junk- yard. Thresher had broken up; hope of determining the specific cause of the accident diminished sharply; the search was over.

Although debris recovered from Thresher underwent careful examination, the exact cause of her loss could not be determined. Evidence pointed to rapid flooding resulting from a hull piping failure. Steps were taken to ensure the integrity of hull piping and other submarine systems. In this case the lessons learned by those working in the deep ocean were as important as the modifications that made submarines safer. Locating the wreck of Thresher had been a marvelous achievement, but severe problems in search – and – navigation systems, organization, and doctrine remained to be solved. In time, they would be. The solutions would be evolutionary, for each new operation pushed the state of deep – ocean work forward.

The Deep Submergence Review Group

Ten days after the Thresher’s loss, Secretary of the Navy Fred H. Korth established a Deep Submergence Review Group chaired by Rear Admiral Edward C. Stephan, then the Oceanographer of the Navy. The dual mission of the Deep Submergence Review Group was to assess the Navy’s capabilities in search, rescue, and recovery of objects and to evaluate the concept represented by saturation diving.

The Deep Submergence Review Group’s charter called for the group to outline programs for immediate development, draft a five – year program to achieve the ultimate capability the Navy and the nation needed, and recommend an organization to carry out the program. The 2,000 – page report of the group affirmed that the Navy lacked the means of operating successfully on rescue and recovery missions in the deep ocean.

Most of the recommendations of the Deep Submergence Review Group, as well as their implementation, are beyond the scope of this chronicle, which is devoted to salvage and the technologies that directly support it. However some of the recommendations did affect salvers. Among these were the group’s recommendations to develop the capability to recover both large and small objects from the deep ocean, develop a more modern submarine rescue system and a surface platform to support it, and pursue an operational saturation – diving capability.”

UNITED STATES SHIP THRESHER (SSN 593)

“The future of our country will always

be sure when there are men such as

these to give their lives to preserve it.”

President JOHN F. KENNEDY, Commander in Chief

In Memoriam

April 10, 1963

It mattered to me and all who served in submarines and nuclear ships

Thanks for sticking with me through the three parts of this story. Thresher played a key part of my upbringing as a submariner as it did for many of my generation and beyond. It spawned more than a feeling of hopelessness that was felt when the boat first went down for its last dive. Many Sub Safe programs and disciplines resulted from her tragic loss. Training and submarine repair were thoroughly reviewed and improved and continuously upgraded year over year. Design changes to every class of submarines and operational standards were completed. All five of my submarines would see the results of the lessons learned. I am incredibly grateful that they were since my first submarine, the George Washington was originally a Skipjack submarine and we got a number of chances to recover from incidents that might have cost us an incredibly high price.

As to the nuclear powered surface fleet, the Navy still has a long way to go before the people who pay the bills (congress) learns the lessons Rickover tried to teach them. Aircraft carriers are mainly nuclear now but the cost to build and operate them is still very high. Yet they are the most reliable units to build a battle group around.

As I think about all the fleet operations my brother Tom and I envisioned back in the 1960’s I wonder how much better it would have been to complete the journey to an all nuclear fleet. But America has always had a split personality when it comes to preparedness. I just hope the young men and women at sea now don’t pay a price for that quirk.

Mister Mac

By the way… say a prayer tonight for all of those who are at sea defending freedom.