What’s in a name?

All Navy ships have a designation. Through the years, technology and advances in design have created the need for new designations. The book Dictionary of American naval fighting ships. v.1. United States categorized all of the ship types used in the American Navy’s history as of 1959. As far as submarines, the following were identified:

- SS – Submarine

- SSA – Submarine Cargo

- SSB(N) – Fleet Ballistic Missile Submarine (Nuclear Powered )

- SSG – Guided Missile Submarine

- SSG(N) – Guided Missile Submarine (Nuclear Powered)

- SSK – Anti-Submarine Submarine

- SS(N) – Submarine (Nuclear Powered)

- SSR – Radar Picket Submarine

- SSR(N) – Radar Picket Submarine (Nuclear Powered)

- SST – Target Submarine

But the Nautilus was certainly a new breed when it was announced.

In July 1951 the United States Congress authorized the construction of a nuclear-powered submarine for the U.S. Navy, which was planned and personally supervised by Captain (later Admiral) Hyman G. Rickover, USN, known as the “Father of the Nuclear Navy.”

On 12 December 1951 the US Department of the Navy announced that the submarine would be called Nautilus, the fourth U.S. Navy vessel officially so named. The boat carried the hull number SSN-571. She benefited from the GUPPY improvements to the American Gato, Balao, and Tench-class submarines.

Nautilus’s reactor core prototype at the S1W facility in Idaho

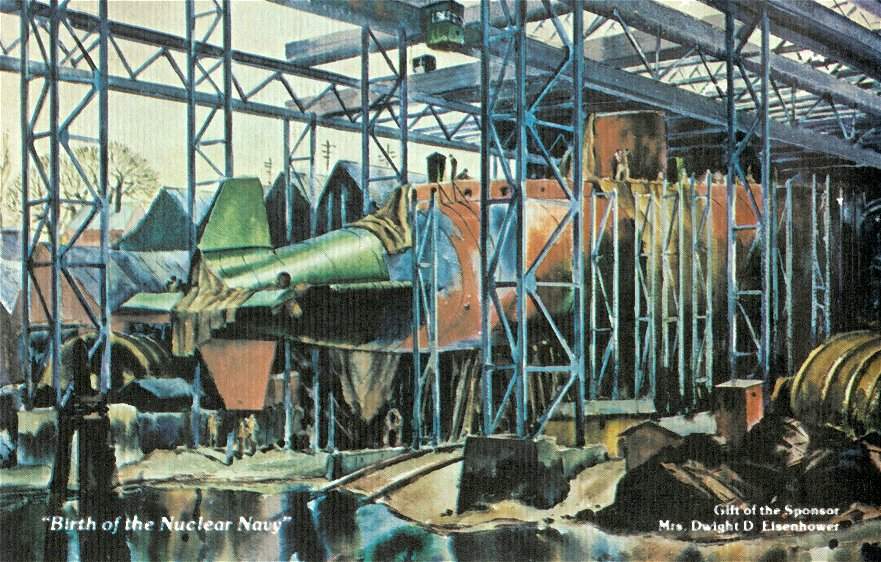

Nautilus’s keel was laid at General Dynamics’ Electric Boat Division in Groton, Connecticut by Harry S. Truman on 14 June 1952. She was christened on 21 January 1954 and launched into the Thames River, sponsored by Mamie Eisenhower. Nautilus was commissioned on 30 September 1954, under the command of Commander Eugene P. Wilkinson, USN.

Of all the submarine names that could have been chosen for the first nuclear power boat, why was Nautilus chosen?

One of the reference materials I have relied heavily on in the past few years was called “Nuclear Navy 1946-1962” written by Richard G. Hewlett and Francis Duncan. This book was an attempt to capture early history of the Navy’s nuclear power program and has a lot of detail that has been obscured from history. The chapter that discusses the keel laying on the Nautilus has a very strong indicator on why “Nautilus” became the name for the flagship that led the nation’s entry into the world of underwater nuclear dominance.

The Keel Laying

“Rickover’s strategy of concurrent development and his January deadline meant that construction of the ship had to begin long before the prototype was completed. In June 1952, while the Electric Boat team was installing the Mark I pressure vessel, steam generators, and primary coolant piping in the hull section at Arco, shipyard personnel at Groton were fabricating hull sections and preparing for keel-laying of the Nautilus.

“A better name for the world’s first nuclear submarine would have been hard to find. In 1801 Robert Fulton had called his experimental undersea boat the Nautilus, and Sir Hubert Wilkins had given the same name to the craft he had used in 1931 in his daring attempt to penetrate beneath the Arctic ice. The United States Navy had assigned the name twice to submarines, first to the H-2 boat in 1913 and then to the SS-168. Launched in 1930, the Navy’s second Nautilus completed fourteen war patrols before being decommissioned in 1945.

“The most famous of all ships bearing the name was the fictional submarine created by Jules Verne. Finding an original edition of Vingt mille lieues sous les mers in the library, Roddis had been fascinated with comparing the specifications of Captain Nemo’s famous craft and those of the new submarine. The nuclear ship would be somewhat longer, a little greater in beam, and of far larger displacement. Verne’s creation, however, could travel at 43 knots with a cruising radius of 43,000 miles, somewhat in excess of the performance then planned for the Navy’s new ship. Instead of nuclear power, Verne’s craft relied on a sodium “Bunsen” apparatus. Whatever hazards this system possessed, presumably radiation was not one of them. Intriguing, too, was the pipe organ in the crew’s lounge. The nuclear Nautilus could never match this

“Choice of the name had been somewhat fortuitous, at least as far as Rickover knew. The Navy practice was to place the names of newly decommissioned submarines at the bottom of a list and then reassign those from the top as new submarines were built. Somehow or other the match was made in the Navy bureaucracy, and on October 25, 1951, Secretary Dan A. Kimball established the designation SSN for nuclear submarines and officially named the first ship the Nautilus.

“Rickover set out to make the keel-laying worthy of a famous name and an historic ship. It was not only a sense of history that stirred his imagination; he also saw a chance to win support for nuclear propulsion. Usually a keel laying was not an occasion for ceremony in submarine construction because there was really nothing sacred about the date. Any one of the midship sections being assembled in the yard could be moved to the building ways when convenient.

“Nothing could assure more attention to an event than attendance by the president. Rickover had enjoyed a session with President Truman at the White House in February 1952. Pleased with Truman’s interest in the project, Rickover thought the president would accept an invitation to speak. Rickover followed political protocol by approaching Senator Brien McMahon. Not only did McMahon come from the state in which the Nautilus was being built, but he was also the Congressional leader most closely connected with atomic energy. As chairman of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, McMahon was deeply concerned about national defense. He had met Rickover at committee meetings and admired his energy and ability. Then at the height of his political power but dying of cancer, McMahon had been mentioned as a possibility for the Democratic nomination as vice-president in the national campaign that year. The keel-laying could bring national attention to the accomplishments of the Truman administration in national defense. Unable to leave his sickbed, McMahon telephoned Truman. The president gladly accepted McMahon’s invitation.

“On June 14, 1952, Truman stood on temporary stands over the building way before a shipyard filled with spectators. Around him were important leaders from industry: John Jay Hopkins, president of General Dynamics, the recently formed corporation of which Electric Boat was a main constituent; Gwilym A. Price of Westinghouse; and Ralph J. Cordiner, the new president of General Electric. The Navy was impressively represented. Secretary Kimball was surrounded by admirals: William M. Fechteler, Chief of Naval Operations; George C. Crawford, commander of the Atlantic submarine force; Calvin M. Bolster, chief of naval research; Homer N. Wallin, chief of the Bureau of Ships; and Evander W. Sylvester, assistant chief of the bureau for ships. In the background and in civilian clothes was Rickover.

“After the inevitable congratulatory remarks and introductory speeches, Truman began. He recalled the role atomic energy had played in his administration: the first nuclear detonation at Alamogordo and the bombs used against Japan which were, for most of mankind, the first knowledge of the power of the atom. The Nautilus was a military project, but the president saw the ship as a step toward peaceful uses of atomic energy. For her use new metals had been made and new machinery designed. Someday these could be used to produce electric power.

“As he concluded, Truman raised his hand. A crane picked up a huge bright yellow keel plate and laid it before the stands. Truman walked down a few steps and chalked his initials on the surface. A welder stepped forward and burned the letters into the plate. The public could have had no better demonstration that the Nautilus was under construction.”

So the answer from the perspective of two men who were tasked with finding answers was that while Nautilus made sense as a name, no one can really claim ownership to the idea. Somehow or other, the name was selected. I have a feeling that this will not sit well with a lot of arm chair historians. Over the past eight years of writing about submarines, I have grown accustomed to hearing from readers who heard from some source they either can’t remember or can’t actually prove that something I wrote was inaccurate. There are a few times when they have been right. I make every effort to correct my errors when they are proven wrong. Frankly, there are some times that I wish things I find were not true. But for today, I am sticking with what I have found.

In the meantime, here is something I discovered while working on today’s story.

This very special cook book contains a recipe that is attributed to the USS Nautilus in 1961.

Dolphin dishes : The submarine cook book : with favorite recipes of the families of the Submarine Force, United States Navy / [Submarine Cook Book Committee] ; illustrations by Retta Scott Worcester; cartoons by Captain Crawford (Bill) Eddy

From the Dolphin Cook book of 1961:

A FAVORITE RECIPE OF A FAMOUS SUBMARINE

USS NAUTILUS (SSN571)

LOBSTER NEWBURG ALA NAUTILUS

2 live lobsters 1/4 teaspoon paprika

1 1/2 cup of butter dash nutmeg

1 cup sherry wine 6 egg yolks, beaten

1 teaspoon salt 2 cups light cream

dash of black pepper

Boil lobster for 15 minutes, cook, remove from shell and dice meat in small pieces. Melt butter in double boiler. Blend in sherry and seasoning. Combine egg yolk and cream. Add egg mixture to lobster slowly, stirring constantly. Cook until thick. Serve on hot toast or in patty shells. Serving for six.

USS NAUTILUS is the world’s first nuclear powered submarine. Commissioned September 80, 1954, Captain Eugene P. Wilkinson, U. S. Navy, commanding ofiiccr and author of these stirring words, “Underway on nuclear power”. First submarine to travel across the top of the world, under the polar ice—August 1958—opening the way for new concepts of commerce and war fare. Commander W. A. Anderson, U. S. Navy, was commanding officer during this historic voyage.

Bon Appetit

Reblogged this on Dolphin Dave.