Killing the Sea Monsters

Two views on submarine versus submarine warfare were recorded after the end of the war where this type of combat was first initiated. Prior to this time, no submarines had been engaged in direct combat with each other. The challenges of the technology, the nature of the sea and the unknowns of the vessels made it nearly impossible for any such combat to have occurred.

But the war brought with it many new challenges and opportunities. Man’s ability to cause new kinds of destruction was unleashed on a global stage. All of the pretenses of chivalry and fairness were obliterated in the massive killing fields on the continent and the wide ranges of the oceans. Even women and children were suddenly thrust into the danger zone.

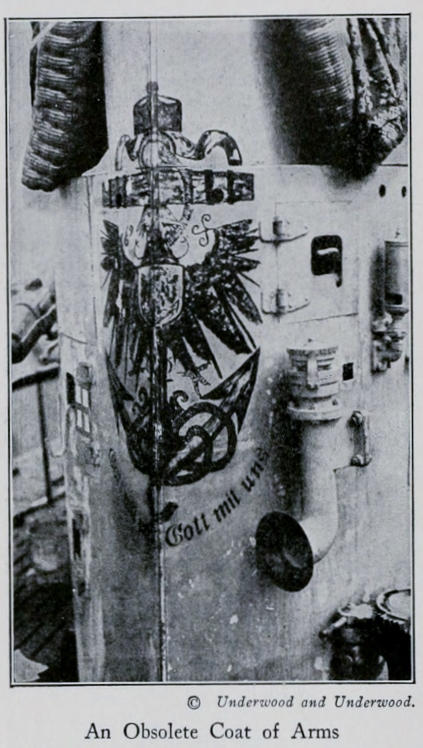

While the Germans were the first to offensively use submarines, it wasn’t long before the British and Americans would see the opportunity to answer the Central Powers in spades.

The American View in 1920

The design of submarines during and after the First World War was influenced in the United States by the Naval Consulting Board. Josephus Daniels was the controversial Secretary of the Navy that formed the board.

“The Naval Consulting Board was not a war organization. It was called into being in 1915, long before America entered the World War, and it gave to naval problems study and research and investigation before the stress of war laid the imperative hand upon all Americans. During the war the individual members of the board, eminent and busy men whose services were in demand by the biggest concerns in the world, forgot their private business and individual pursuits and were as fully and wholeheartedly enlisted in the service of their country as any man who fought on land or sea. The president of the board, Mr. Thomas A. Edison, left his laboratory and practically became a naval officer, spending long months in the Navy Department and extended periods of deep-sea cruising that he might be in the closest touch with the problems to be solved. Other members of the board gave themselves and their talent as fully.”

SUBMARINES USED AGAINST SUBMARINES.

“Submarines have very low visibility. They were primarily designed to operate against the large surface vessels, and it has been the general impression that submarines are not effective against submarines. This belief was also held by the general naval staffs of the various combatants at the beginning of the war; however, allied submarines have been successfully used in destroying enemy submarines.

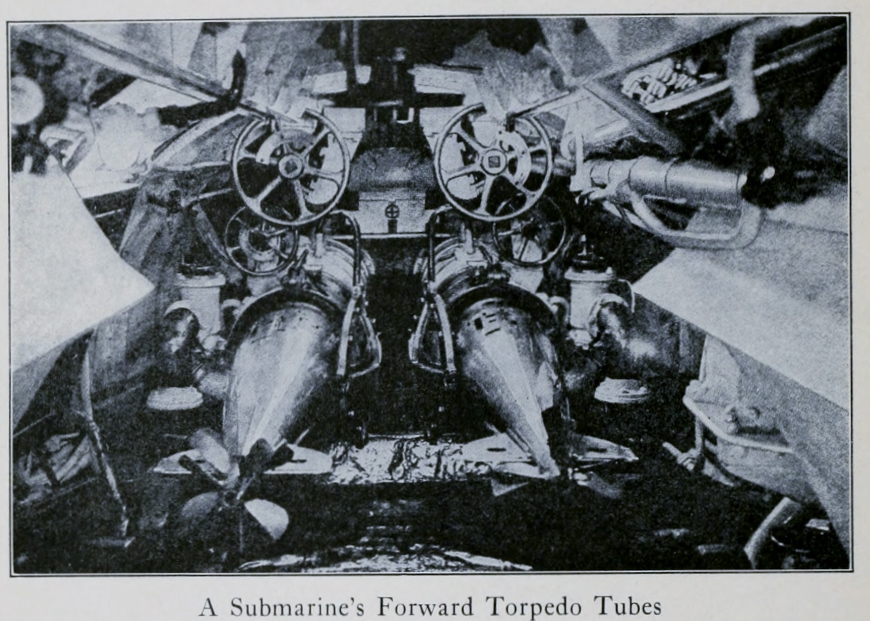

In operating against hostile submarines, the hunting submarine may employ one of two methods — it may remain totally submerged and take observations by thrusting up the periscope every few minutes, or it may remain on the surface and only dive when the enemy submarine is sighted. In both cases the hunting submarine maneuvers very slowly, in order to avoid attracting the attention of the enemy, and to prevent detection by means of listening devices. The method of total submergence is used in restricted waters, such as channels and lanes through which the enemy submarine must pass. Torpedoes are used when submarines fight each other, and, if possible, the extremely effective ram. All submarines can ram without specially designed devices for so doing.”

Naval Consulting Board of the United States, by Lloyd N. Scott, late captain, U.S.A., and liaison officer to the Naval Consulting Board

Washington, Govt. Print. Off., 1920

DUELS BETWEEN SUBMARINES

Harper’s pictorial library of the world war … New York Harper & brothers, [c1920]

EARLY in the war experts informed us that the submarine itself was useless for fighting the submarine because it was too blind. During the war, however, this dictum went overboard along with several other pre- war notions. Sir Henry Newbolt, in his book Submarine and Anti-Submarine, collected a number of tales of submarine duels, of which the following are examples:

“Let us take first the case of E-54, Lieut. Com. Robert H. T. Raikes, which shows a record of two successes within less than four months — one obtained with comparative ease, the other with great difficulty. The first of the two needs no detailed account or comment. E-54, on passage to her patrol ground, had the good fortune to sight three U-boats in succession before she had gone far from her base. At two of these she fired without getting a hit; but the third she blew all to pieces, and picked up out of the oil and debris no less than seven prisoners.

“Her next adventure was a much more arduous one. She started in mid-August on a seven-day cruise, and in the first four days saw nothing more exciting than a neutral cruiser carrying out target practice. On the morning of the fifth day, a U-boat was sighted at last; and after twenty-five minutes’ maneuvering, two torpedoes were fired at her, at a distance of 600 yards, with deflection for eleven knots. Her actual speed turned out to be more nearly six or seven knots, and both shots must have missed ahead of her. She dived immediately, and a third torpedo failed to catch her as she went down.

“An hour and twenty minutes afterward she reappeared on the surface, and Lieutenant-Commander Raikes tried to cut her off, by steering close in to the bank by which she was evidently intending to pass. E-54 grounded on the bank, and her commander got her off with feelings that can be easily imagined. Less than an hour after, a U-boat — the same or another — was sighted coming down the same deep. Again Lieutenant-Commander Raikes tried to cut her off, and again he grounded in the attempt. He was forced to come to the surface when the enemy was still 2,000 yards away. To complete his ill-fortune, another U- boat was sighted within an hour and a quarter, but got away without a shot being possible.

“Twenty-four hours later the luck turned, and all these disappointments were forgotten. At 2.6 p. m. Lieutenant-Commander Raikes sighted yet another U-boat in open water, on the old practice-ground of the neutral cruiser of three days before. He put E-54 to her full speed, and succeeded in overtaking the enemy. By 2.35 he had placed her in a winning position on the U-boat’s bow and at right angles to her course. At 400 yards’ range he fired two torpedoes, and had the satisfaction to see one of them detonate in a fine cloud of smoke and spray. When the smoke cleared away the U- boat had completely disappeared; there were no survivors. Next day, after dark, E-54’s time being up, she returned to her base, having had a full taste of despair and triumph.

READY FOR A LIGHTNING SHOT

“Earlier in the year, Lieutenant Bradshaw, in G-13, had had a somewhat similar experience. He went out to a distant patrol in cold March weather and had not been on the ground five hours when his adventures began. At 11.50 a. m. he was blinded by a snow-squall; and when he emerged from it, he immediately sighted a large hostile submarine within shot. Unfortunately the U-boat sighted G-13 at the same moment, and the two dived simultaneously. This, as may easily be imagined, is one of the most trying of all positions in the submarine game, and so difficult as to be almost insoluble. The first of the two adversaries to move will very probably be the one to fall in the duel; yet a move must be made sooner or later, and the boldest will be the first to move.

“Lieutenant Bradshaw seems to have done the right thing both ways. For an hour and a half he lay quiet, listening for any sign of the U-boat’s intentions; then, at 1.30 p.m. he came to the surface, prepared for a lightning shot or an instantaneous maneuver. No more complete disappointment could be imagined. He could see no trace of the enemy — he had not even the excitement of being shot at. On the following day he was up early, and spent nearly eleven fruitless hours knocking about in a sea which grew heavier and heavier from the south-southeast. Then came another hour which made ample amends.

A LONG SHOT IN ROUGH WATER

“At 3.55 p.m., a large U-boat came in sight, steering due west. Lieutenant Bradshaw carried out a rapid dive and brought his tubes to the ready courses and speeds as requisite for attack.

“The maneuvering which followed took over half an hour, and must have seemed interminably long to everyone in G-13. At 4.30 the enemy made the tension still greater by altering course some 35 degrees. It was not until 4:49 that Lieutenant Bradshaw found himself exactly where all commanders would wish to be, eight points on the enemy’s bow. He estimated the Q-boat’s speed at eight knots, allowed l8 degrees’ deflection accordingly, and fired twice. It was a long shot in rough water, and he had nearly a minute to wait for the result. Then came the longed-for sound of a heavy explosion. A column of water leapt up, directly under the U-boat’s conning-tower, and she disappeared instantly. Ten minutes afterward, G-13 was on the surface, and making her way through a vast lake of oil, which lay thickly upon the sea over an area of a mile. In such an oil-lake a swimmer has no margin of buoyancy, and it was not surprising there were no survivors to pick up. The only relics of the U-boat were some pieces of board from her interior fittings.”

TWO “SUBS” IN A DEATH GRAPPLE

In one instance two submarines caught sight of each other and charged like old time knights. The British vessel was the E-50. According to Sir Henry Newbolt:

“The British commander drove straight at the enemy at full speed, and reached her before she had time to get down to a depth of complete invisibility. E-50 struck fair between the periscopes; her stem cut through the plates of the U-boat’s shell and remained embedded in her back. Then came a terrific fight, like the death-grapple of two primeval monsters.

The German’s only chance, in his wounded condition, was to come to the surface before he was drowned by leakage; he blew his ballast tanks and struggled almost to the surface, bringing E-50 up with him. The English boat countered by flooding her main ballast-tanks and weighing her enemy down into the deep. This put the U-boat to the desperate necessity of freeing herself, leak or no leak. For a minute and a half she drew slowly aft, bumping E-50’s sides as she did so; then her effort seemed to cease, and her periscopes and conning-towers showed on E-50’s quarter. She was evidently filling fast; she had a list to starboard and was heavily down by the bows.

As she sank, E-50 took breath and looked to her own condition. She was apparently uninjured, but she had negative buoyancy and her forward hydroplanes were jammed, so that it was a matter of great difficulty to get her to rise. After four strenuous minutes she was brought to the surface, and traversed the positions, reaching for any further sign of the U-boat or her crew. But nothing was seen beyond the inevitable lake of oil, pouring up like thick, rank, life-blood of the dead sea-monster.”

This was the opening paragraph in the section of his book that talked about submarine versus submarine warfare:

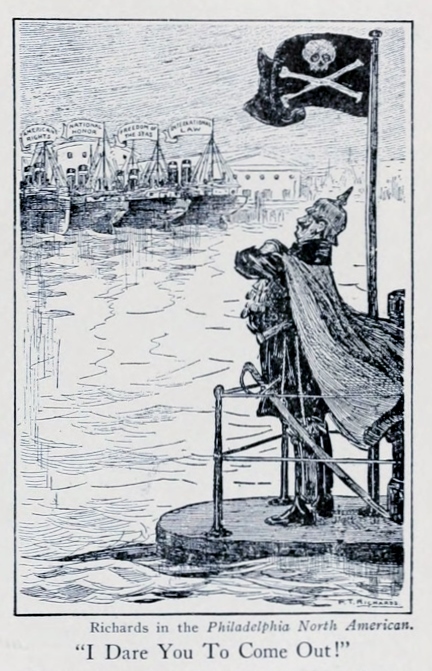

“Since submarines must be hunted, there is something especially attractive in the idea of setting other submarines to hunt them; it seems peculiarly just that while the pirate is lying in wait under water for his victim, he should himself be ambushed by an avenger hiding under the same waters and possessed of the same deadly weapons of offence.”

As I think about the progress that would need to be made towards the ultimate goal of submarine versus submarine over the next few decades, this statement really captures the idea.

The resulting Fast Attack variant of submarine was the only logical conclusion.

Mister Mac

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

As always love the writing and learned from the research you have done.