In January of 1973, I attended submarine school in New London Connecticut. I had completed basic training and Machinist Mate “A” school and this was my next assignment in the pathway to my first submarine. It’s funny when I think back now how much I was anxious to leave home and get away from school. The Navy has a wicked sense of humor since it kept sending me to school after school after school. By the time I would retire, those schools would amount to over sixty technical and leadership schools.

But sub school was special. We lived in open bay barracks and had very little privacy. In many ways it was like being back in boot camp again except it was a heck of a lot colder and there were a lot more trips to town to discover how much alcohol you could absorb before running out of money. I don’t remember the names of any of the bars now. I think that is a combination of the fog of 46 years of living and the fog of not remembering where we were at the time after the first ten rounds.

I somehow managed to graduate anyway. What little I remember about the curriculum was that we studied two types of submarines: 616/640 Class boomers and 637 Class Fast Attacks. I had to sign a card for the study guides and was threatened with jail time if I lost them. There was also no talk about diesel boats at that point. Maybe some of the older men mentioned them but only in the context of “you nubs will never know what being a real submariner is now that they are giving all of the real submarines away”. I do remember feeling a bit cheated that I would never serve on a real submarine although we were encouraged to request duty on them as we prepared to graduate.

As it turns out, I was stationed on board a submarine that was as close in age to a diesel boat as you could get… for a boomer anyway. All of the books I studied in sub school and all of the lessons I would learn in Auxiliary Package course were based on the newer boats. There were a few things that were similar on the 598 (the trim pumps remained the same for decades to come) and the fundamentals were the same. But I think I learned most of my real knowledge and skills on the deck plates. After all, we were at sea and there were no convenient bars to wash away the knowledge every night.

Today’s story is about the Simon Bolivar.

In 1994, the Simon Bolivar returned from its 73rd and final strategic nuclear deterrent patrol, 28 years after it departed port for its 1st patrol

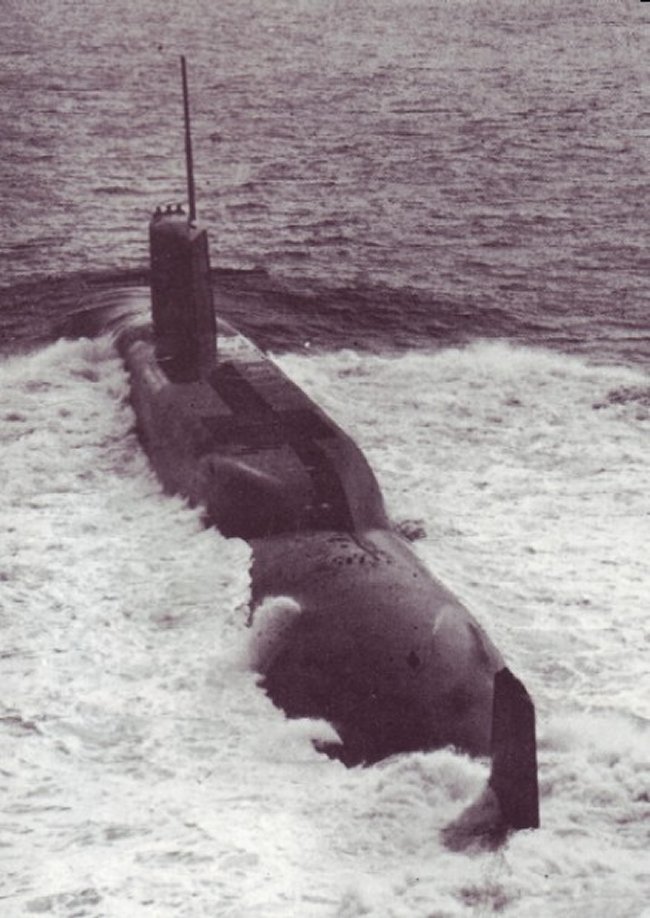

USS SIMON BOLIVAR was the second BENJAMIN FRANKLIN – class nuclear powered fleet ballistic missile submarine. Generally similar to the LAFAYETTE – class, the twelve BENJAMIN FRANKLIN – class submarines had a quieter machinery design, and were thus considered a “separate class”.

SIMON BOLIVAR (SSBN-641) was laid down on 17 April 1963 by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Co., Newport News, Va.; launched on 22 August 1964; sponsored by Mrs. Thomas C. Mann; and commissioned on 29 October 1965, Comdr. Charles H. Griffiths commanding the Blue Crew and Comdr. Charles A. Orem commanding the Gold.

In late December 1965 and most of January 1966, the submarine underwent demonstration and shakedown operations.

The normal routine for fleet ballistic missile submarines is for the Gold Crew to make a patrol and then alternate with the Blue Crew. The Gold Crew successfully fired an A-3 Polaris missile off the coast of Cape Kennedy on 17 January, and the Blue Crew completed a successful missile firing two weeks later. In February, the Gold Crew continued shakedown operations in the Caribbean. The following month, her home port was changed to Charleston, S.C., and minor deficiencies were corrected during a yard availability period. Beginning in April, the Blue Crew prepared for and conducted the first and third regular Polaris patrols. The Gold Crew meanwhile entered the training period and later conducted the second patrol, finishing the year in a training status. SIMON BOLIVAR completed her third deterrent patrol in January 1967, operating as a unit of Submarine Squadron (SubRon) 18.

This routine continued until 7 February 1971 when the submarine returned to Newport News for overhaul and conversion of her weapons system to Poseidon missiles.

SIMON BOLIVAR departed Newport News on 12 May 1972 for post-overhaul shakedown operations and refresher training for the two crews which lasted until 16 September. The end of 1972 found the submarine back on patrol.

Into August 1974, the Blue and Gold Crews have alternated in keeping the fleet ballistic missile submarine on deterrent patrols, providing the United States with instant retaliatory capabilities in case of attack.

[Deactivated while still in commission in September 1994, SIMON BOLIVAR was both decommissioned and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 8 February 1995. She entered the Navy’s Nuclear Powered Ship and Submarine Recycling Program in Bremerton, Washington on 1 October 1994 and finished in on 1 December 1995. When she emerged from the program, the former ballistic missile submarine ceased to exist as a complete ship and was classed as scrapped.

General Characteristics: Awarded: November 1, 1962

Keel laid: April 17, 1963

Launched: August 22, 1964

Commissioned: October 29, 1965

Decommissioned: February 24, 1995

Builder: Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., Newport News, Va.

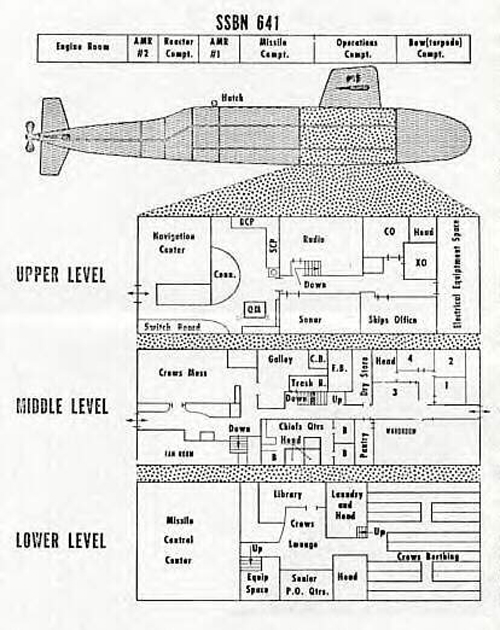

Propulsion system: one S5W nuclear reactor

Propellers: one

Length: 425 feet (129.6 meters)

Beam: 33 feet (10 meters)

Draft: 31.5 feet (9.6 meters)

Displacement: Surfaced: approx. 7,250 tons; Submerged: approx. 8,250 tons

Speed: Surfaced: 16 – 20 knots; Submerged: 22 – 25 knots

Armament: 16 vertical tubes for Polaris or Poseidon missiles, four 21″ torpedo tubes for Mk-48 torpedoes, Mk-14/16 torpedoes, Mk-37 torpedoes and Mk-45 nuclear torpedoes

Crew: 13 Officers and 130 Enlisted (two crews)

A South American soldier, statesman, and revolutionary leader, Simon Bolivar was born in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1783. He fought under Francisco Miranda in a revolt against the Spanish in 1810 but was forced to flee. He planned and led another revolution in Venezuela (1815 to 1818) which was successful.

Bolivar raised a small army in New Granada (now Colombia) and defeated the Spanish at Boyaca in 1819 and was subsequently made president of the new republic of Colombia with almost supreme power.

In 1821, Bolivar marched south to Quito, Ecuador. In August 1824, his army defeated the Spanish in the battle of Junin which, with General Antonio Sucre’s victory at Ayacucho in December, freed Peru from Spain. Bolivar organized a new republic, named Bolivia, in 1825.

Simon Bolivar died on 17 December 1830 on his estate near Santa Marta, Colombia.

From Admiral Rickover’s Book Eminent Americans:

USS SIMONBOLIVAR (SSBN 641)

NAMED FOR a great American soldier, patriot and statesman. Simon Bolivar (1783—1830) was American in the broad sense of the word prevailing south of the border, where it is applied to citizens of the entire Western Hemisphere, north, central and south.

Not only for us, but for all who share this vast continent with us, the word has a magic of its own. It stands for what we have in common, what gives us a sense of belonging to the same family of nations, despite the fact that we differ in many important respects. Not the least of the bonds uniting us is a revolutionary heritage that is peculiarly American.

What sets America’s wars of independence apart from other struggles for colonial emancipation is that they were fought for political liberty, pure and simple. They were wars led in the north by Englishmen and in the south by Spaniards against men of their own race, language and culture who would deny them the right to self-government. The leaders of the revolt laid down their “lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor” from motives of pure patriotism unadulterated by desire for personal advantage. They were already successful and important men in their communities; they did not expect independence to enrich them or to enhance their status. They fought for the ideal of liberty at great personal risk. None risked more and gained less personally than Simon Bolivar.

Born in Caracas, Venezuela in 1783—the year England recognized the independence of the United States—the son of a wealthy and aristocratic Spanish family long settled in the colony, Bolivar was educated abroad and, until the age of 27, lived the pleasant life of a rich planter. But from the moment of the first revolt in Caracas against Spain in 1810 to the end of his brief life of but 47 years, Bolivar served almost continuously as leader of the revolt. He richly deserved the title Liberator bestowed on him by his countrymen, for he succeeded in driving the Spaniards from the vast area now occupied by the Republics of Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru. At one time or another he was not only the military leader but civilian chief as well of one or more of these Republics; for a brief time all were united under him.

The Hispanic-American wars of independence lasted twice as long as did our own, and were fought over a vastly larger area and more intractable terrain. In population, the adversaries were more evenly matched, there being 11 million Spaniards to 15 million colonials, while we had but a third as large a population as England. Spain at the time was weakened by the Napoleonic Wars while England was the premier maritime empire of the world. On the other hand, the Spanish colonials had to fight with no outside help except for individual volunteers who flocked to Bolivar’s army as they did to Washington’s. No major country gave aid as we received from France.

Only little Haiti, under President Pétion, supported the cause of freedom by giving men and materiel to Bolivar at a time when he sorely needed them.

Of his military feats, Thomas Carlyle said that Bolivar rode“fighting all the way, through torrid deserts, hot mud swamps, through ice-chasms beyond the curve of perpetual frost—more miles than Ulysses ever sailed.” He “marched over the Andes more than once, a feat analogous to Hannibal’s and seemed to think little of it. Often beaten, banished from the firm land, he always returned again, truculently fought again.”

Henry Clay called Bolivar the Washington of South America. Indeed, there are striking similarities, but the differences in temperament and in the turn of their lives are equally great.

Both were self-taught soldiers. Bartolomé Mitre, famed Argentinean statesman, journalist, author and historian said that though Bolivar “had no military education, he possessed the talents of a great revolutionary leader and the inspiration of genius . . . He formed his plans quickly and executed them with daring resolution, while he lost no time in securing the fruits of his victory.” And, speaking of his reconquest of western Venezuela, he remarked that “never, with such small means, was so much accomplished over so vast an extent of country, in so short a time.”

Like Washington, Bolivar had that quality without which no man becomes a great military leader—a capacity to bear adversity with fortitude and to rise from defeat to win victory. His Spanish adversary General Morillo said that Bolivar was “more fearful vanquished than victorious”-just as of Washington one might well say that his finest hour was Valley Forge.

Both cared for the welfare of their troops and were generous toward them. Both in their lifetime received much public adoration, both have a secure place in history as liberators of their nations. A South American Republic was named for Bolivar, an American State for Washington.

But, while Washington remained popular and died venerated by his countrymen on the estate he loved so well, Bolivar lost the support of his people and died penniless of a lung ailment which might not have proved fatal had he spared himself.

Toward the end he was discouraged and said that “those of us who have toiled for liberty in South America have but plowed the sea.” Hendrik Willem Van Loon, in his biography writes an epitaph that is more just. “If those words, spoken in the bitterness of his final defeat and loneliness, had truly been the summing up of his restless labors, the life of Simon Bolivar might well have been considered a hopeless failure. Whereas a single glance at the map of the southern half of our continent proclaims the glory of his achievements. Half a dozen free and independent nations, arisen from among the ruins of Spain’s imperial ambitions, are surely a monument of which any human being might well feel proud.”

The Submarine Simon Bolivar has a Facebook page if you want to reconnect with the men who sailed on her. https://www.facebook.com/groups/39659413900/

Great article brother. I remember my time on the Bolivar well. She was a great boat. I noticed a pic that you had of her being commissioned from Newport News. I’ve looked for one like that, but have never found one. Would you mind sharing that pic via email?

Thanks again!!

Michael DeLand

The source for the picture is the Navy web site: http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08641.htm Click on any of the pictures there and save to your Pictures file on your computer

You can email me at bobmac711@live.com if that doesn’t work

Mac

Michael, Are you able to share your Simon Bolivar memories with me? I am writing a book about the United States military presence in Scotland during the Cold War. Simon Bolivar operated from Holy Loch.

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History and commented:

#DaveLovesSubmarines

My uncle ran an Attack Teacher at the Submarine School in 1945. https://joynealkidney.com/2018/04/16/delbert-wilson-submarine-attack-teacher/