Previous post: If you had not read the previous post, here is the link. At the end of the story, I will link them all together on one page here on the blog.

Chapter One: Plebes is Plebes

St Swithun’s day if thou dost rain

For forty days it will remain

St Swithun’s day if thou be fair

For forty days ’twill rain nae mare

It rained on St. Swithun’s day. According to the Democratic Advocate, on Monday July 15, 1912, rain came to the Maryland shores to offset the typical heat of summer. In nearby Annapolis, an aspiring young man from the District of Columbia was beginning a journey that would take him around the world and end far too soon.

Plebe summer.

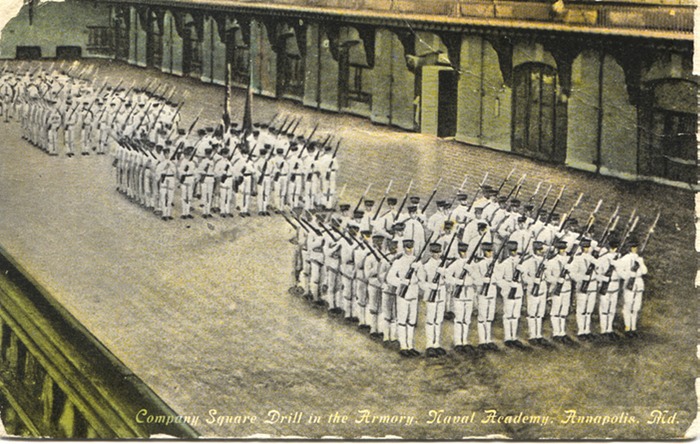

An inglorious time when the chosen men would have their first taste of life at the Naval Academy. The joys of boyhood would soon be a pleasant memory that could only creep in during the isolated hours of the night. For the next four years, these lads would learn about science and mathematics and steam and weaponry. They would drill and march and stand for hours on end at attention while senior classmen practiced the age old art of discipline within the ranks. One of those Plebes was a young man named Cassin Young. Cassin had grown up in Washington DC and in Wisconsin but it was Wisconsin that helped him to gain entry into this life of adventure. In July of 1912, he joined a group of other young men who were soon to learn about the foundations of the Old Navy and prepare for a New Navy that would be radically different than its beginnings.

But one thing had not changed. In order to begin the journey as a naval officer, one still had to start from the beginning. Before they could become an officer, each candidate had to be molded in an age old custom that still remains intact in many ways today. The page from the Academy’s yearbook for 1913 best describes the wretched condition of the new men.

“Plebes is Plebes”

“First there was the Plebe Summer. Hot – Lordy! Can’t you smell the stencil ink and that salt sea air that is the special peculiarity of Crabtown Harbor? Drills, drills, drills – infantry, seamanship, steam, gymnasium – above all gymnasium. Feet, close! Feet full open! “Every Swedish Movement has a meaning all its own.””

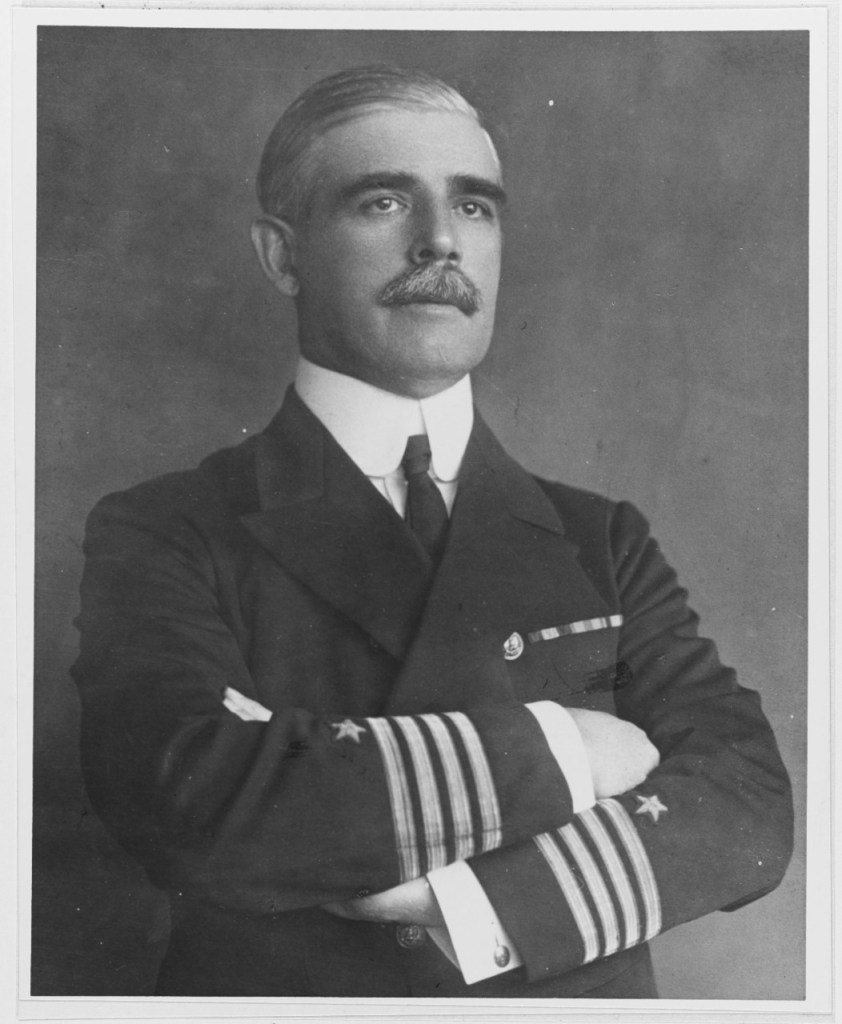

The “Swedish Movements” mentioned was one of the many innovations that came to the Academy in the summer of 1912. Change was in the wind for the entire establishment. The new Commandant’s name was Captain John H. Gibbons. Under his administration five major changes would sweep through the dusty old halls of the Academy and reach all the way out to the far-flung fleet.

In his 1912 report to the President, Secretary Meyer stated that:

“PHYSICAL TRAINING.

Attention has been given to developing a proper system of physical training that may be uniform throughout all branches of the Navy to replace the existing physical drill, which does not inculcate habits of care, strength, and activity to the degree attained by the more scientific method, which has already been introduced at the Naval Academy with marked success. A special feature has been made of swimming, all midshipmen being required to qualify thoroughly before receiving their diplomas; and a higher standard being established for the swimming qualification in the fleet for both officers and men.

The officers ‘ physical test has been changed to a 10 – mile walk monthly, which has removed any irksomeness, while increasing the benefit derived.”

Navy Secretary Meyer had also recently noted that “poor ships may be made to give a good account of themselves in the hands of skillful officers, but the best ships can accomplish nothing if they are not well commanded. Moreover, on the brains and skill and energy of the young men now being trained at the Naval Academy must depend the future efficiency of the fleet, for on the will fall the responsibility of designing as well as fighting the navy of the future.”

These were indeed prophetic words. During President Theodore Roosevelt’s times, the importance of a global naval presence had shown itself in many ways. The dramatic way the Japanese fleet defeated what should have been a superior Russian Navy was a portent of things to come. The old order where a nation could hide behind its oceans was rapidly coming to an end. In order for the Navy to keep up with the challenges of the future, a first class fleet needed a first class set of officers and highly trained sailors to man them. The heart of the change had to start with the Naval Academy that was the sole source for leadership development for prospective officers at the time.

The five reforms Commandant Gibbons set in place in the summer of 1912 were (1) the facilitation of admission of candidates; (2) the simplification of the curriculum: (3) the substitutions of naval officers for civilian teachers wherever possible; (4) the elimination of hazing, and (5) the “dignification” of the first class. All of these reforms were meant to modernize an institution that was as traditional as the sun rising in the east and setting in the west. In other words, like every reformer, Gibbons would find himself sailing against a very strong tide.

Captain Gibbons was a hard case reformer that wanted to “right the ship” at the Academy. From the physical conditioning to the structural changes of the Academy itself, he ruffled many feathers along the way. Gone were the large numbers of civilian teachers and gone was the hands off approach to discipline within the midshipmen themselves. He was someone who detested drinking, gambling and hazing and wanted to make sure that under his watch these practices would be abolished once and for all.

None of this probably meant very much to Cassin Young or the men who would accompany him through his four years of training. He had been born in the bustling town of Washington in the District of Columbia to a druggist and his homemaker wife during a time when the old century was dying and the new one was just about to begin. The city was representative of that change. While the streets were mostly paved, horses were still the primary means of travel both inside and outside of the city. But it was a busy city. Electric street cars were starting to replace the horses in some areas bringing both convenience and tragedy. One story in late March speaks of an adventurous boy trying to cross the in front of a trolley while it was traveling at the break neck speed of twenty miles per hour. Citizens were outraged that these death dealing devices lacked the needed safety equipment to prevent such a tragedy.

Cassin Young was born on March 6, 1894, in Washington, District of Columbia, his father, Peter, was 27 and his mother, Annie, was 25. He married Eleanor Hayden McFadden in 1919 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. They had five children during their marriage.

The year Cassin Young was born, America was still recovering from a great Civil War and Washington had been at the center of that war. Reading the new newspaper called the Washington Times, one could find out about all of the latest scandals in government, affairs of the heart that had gone wrong and the darker side of a country not quite freed from its post antebellum past. Tariffs were all the rage in Congress and immigration issues flared up concerning falsified papers and illegal residents from Italy and Ireland. A march on Washington to seek relief from a long period of economic depression coincided with the day of his birth.

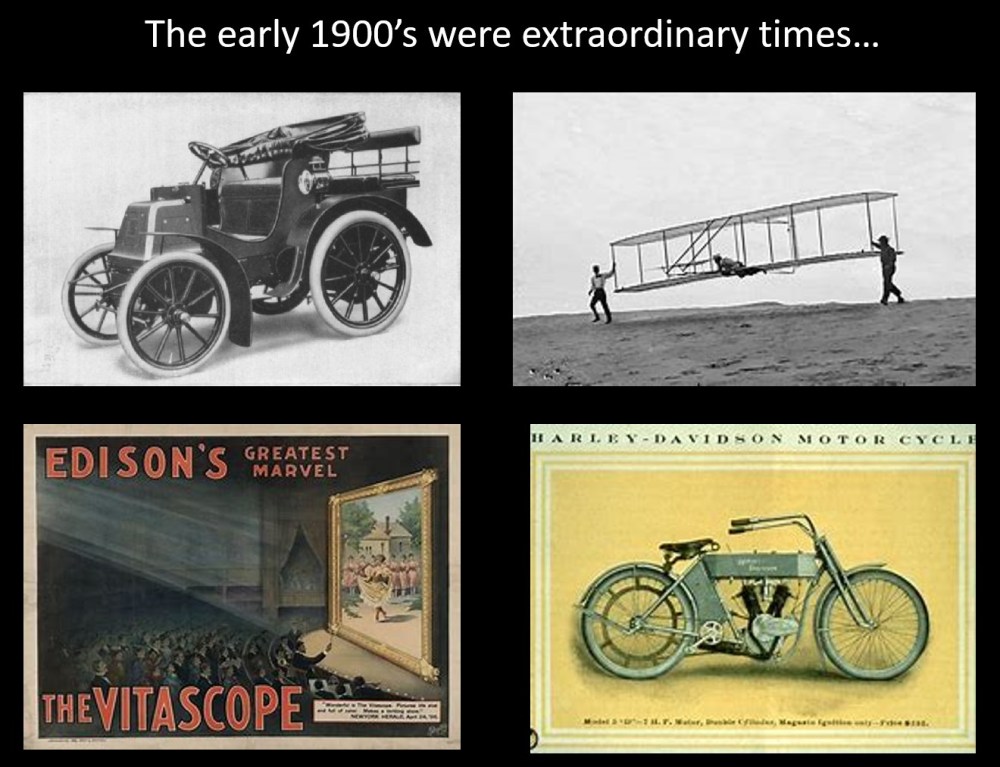

When the century turned, the five year old year old probably didn’t notice all of the commotion of the age. The Front Page of the Washington Times on January 1 showed a picture of Father Time driving an automobile with a horse lying on its side back in the distance. The caption asked simply “What Next?”

What next indeed. America had just fought a war with Spain on a nearly global basis and had achieved a victory. Key to that victory was a United States Navy that was still trying to find its own identity. This large collection of ships included ships that sailed under cloth while grudgingly adapting to the steam from a coal fired boiler. Electricity was in its infancy and wireless was only now becoming a reliable method for communication. Many of the ships that sailed to beat the Spanish Navy were carry-overs from the last Great War and the men in charge soon realized that in order to be a world class navy, many changes would need to occur. Some would even serve in the Great War that was to come with varying degrees of success. Large gunboats that struggled to keep up in the heavy seas and challenging environments of the Caribbean were harbingers of changes that could need to be made to effect a true global navy. But those days were still in the future.

President and Mrs. McKinley greeted thousands at the White House on New Year’s Eve, basking in the glow of electric lights and listening to the sounds of eleven buglers welcoming the President and First Lady to the grand reception. Representatives from twenty eight countries were welcomed into the White House that night which included delegates from as far away as Japan and China. Most impressive to the observers though was the contingent of military officers that arrived in a traditional march.

When the President and his party were present, the line of Army, Navy and Marine officers who had assembled at the War Department marched two abreast in their gleaming and bright uniforms covered with gold and medals from the recent war. Citizens of Washington lines the way as these brave men of honor marched to the brightly lit assemblage and added a sense of vision to what the next century would be like. America had found its sea legs on a global scale and this evening was just a taste of the thigs to come.

But no change happens without pain. There is always a price to be paid for the convulsions that occur with any change. While America had prospered greatly under President McKinley since his election in 1896, not all had prospered equally. An assassin who was a known anarchist saw his chance on September 6, 1901, the fate of the nation was forever changed. McKinley’s Vice President, former Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, would take the helm of the emerging ship of state and sailed it further than anyone could have imagined. Roosevelt would propel the nation and the navy forward with boundless enthusiasm and vision. The world and the United States would never be the same again.

One of Roosevelt’s actions that would have far reaching consequences was his order directing the Great White Fleet to sail around the world.

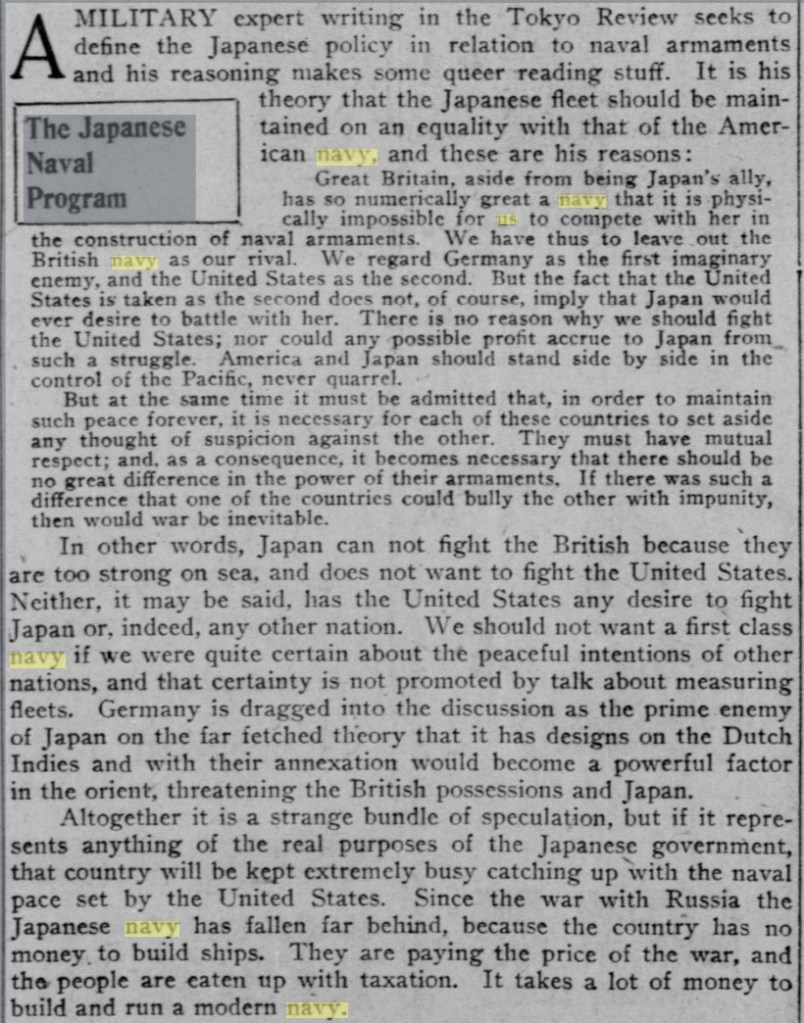

This massive show of force was not by accident. Even in the early years of the 20th century, the balance of power was beginning to shift away from the older navies. Japan’s defeat of a larger Russian fleet at the Battle of Tsushima was a shock to the sensible leaders of the world. Japan early on understood technology and borrowed and copied from the best. They also learned naval tactics well and improved upon the ideas that many great naval leaders had instituted. She developed her own schools but still sent students abroad to learn the tactics of potential enemies. This would be painfully evident in the early part of the Second World War.

The Navy itself had to come to grips with the limitations exposed by the sailing of the Great White Fleet. The sailing of the ships was marked with serious shortfalls in supplying those ships with the needed energy. Coal was the new king and as the ships travelled, there were only two methods of replenishment: you brought it with you on board ships called colliers or you paid a high premium in whatever port you might find that actually had coal. The quality of coal was important to the efficiency of the boilers. Bad coal or coal that was contaminated would certainly impact the speed and progress of the fleet.

The Secretary of the Navy reported in his annual report to the President:

Fuel (Page 37 of the report)

The highest grade of steaming coal from the Pocahontas, New River, Georges Creek and Eureka fields has been supplied the fleet at the lowest market prices. The department, through its arrangements with coal suppliers, is able to load on short notice about 4,000 tons per day at Hampton Roads and Baltimore

The Navy is still in need of better fuel depots for the fleet at several important strategic points, notably Guantanamo, Puget Sound and Pearl Harbor. The capacities and facilities of these stations are being increased as far as practical with the funds available.

The fuel stations at Frenchman’s Bay, ME., and New London Conn. Have been closed.”

There were a few extra notes about the addition of oil storage for future use. But the need for ships to transport the coal was still high on the priority list.

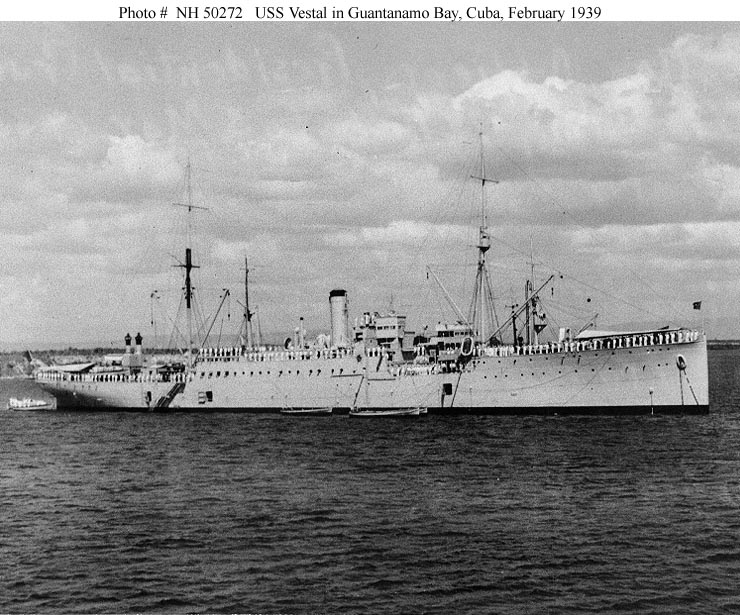

One of those coal ships was a collier that ultimately became the USS Vestal. The history of USS Vestal (AR-4) began when Erie (Fleet Collier No. 1) was authorized on 17 April 1904; but the ship was renamed Vestal in October 1905, well before her keel was laid down on 25 March 1907 at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, New York. Launched on 19 May 1908, Vestal was placed in service as a fleet collier, with a civilian crew, at her builders’ yard on 4 October 1909.

Vestal served the fleet as a collier, operating along the Atlantic coast and in the West Indies from the autumn of 1909 to the summer of 1910. After a voyage to Europe to coal ships of the Atlantic Fleet in those waters, the ship returned to the Philadelphia Navy Yard and was taken out of service at the Boston Navy Yard on 25 October 1912. The ship underwent nearly a year’s worth of yard work and was commissioned as a fleet repair ship in 1913 under the command of Commander Edward L. Beach, Sr., USN (father of submariner Captain Edward L. Beach, Jr.).

William Howard Taft was President the day Young entered service. He had taken over after Roosevelt finished his time. During the McKinley administration and into Roosevelts first term, Taft served as the civilian governor in the Philippines. This experience would carry on to his later role as President and he had an eye towards the Far East as he shuffled the State Department. He ended up being a one term President but his long term legacy was a continuation of Roosevelt’s approach to the island nation of Japan. This focus would play a role in the generations to come as Japan grew in strength and ambition.

On July 8th, the Washington newspapers announced that a naval appropriations bill of $133,609,674 had been passed. This was the largest appropriations bill ever allowed and called for two new first class battleships and increased the number of submarines from four to eight.

In reality, only one was built.

Replacement ships for the Indiana, Oregon, and Massachusetts should have been laid down in 1910, for the Iowa in 1912, and new replacement ships should have been begun for the Kentucky and Kearsarge in 1915. These matters, together with the shortage of 3 battleships already existing in 1911, were taken into consideration by the General Board in making its recommendations for a 4-battleship program in both 1912 and 1913.

One battleship only was provided for in each of these two years, increasing the shortage in the original 48 battleship program to 5, without considering replacement ships for the Indiana, Oregon, Massachusetts, and Iowa, already overdue for authorization. Even before Young began his naval career, the strength that was going to be needed in naval armaments was already behind the projected needs.

On a hot summer’s day in July of 1912, Cassin Young’s time preparing for his entrance into the Naval Academy at the St. John’s Academy came to an end. Politics and the world’s situation were probably far from what was immediately on his mind. He was now in the thick of a refining experience that would set the course for the rest of his life. He was a Plebe entering the United States Naval Academy. That smell of stencil ink, shoe polish and salt sea air were about to enter his conscious and remain there for the rest of his shortened life.

He would also gain a quick and long-lasting exposure to tragedy and sudden death. It is hard to imagine that what was about to happen would not have a profound impact on the rest of his Navy career.