Of all the fears I have ever had, being trapped in a sunken submarine is one of the biggest.

The second biggest fear is finding out firsthand where crush depth is

(My submariner nephews always accused me of serving on the both the Turtle and the Holland. This is dedicated to them.)

Over the course of my lifetime, my fears have evolved.

I’m sure most people would say the same thing. As a young boy, I was afraid of roller coasters and not being in control of the things around me. It’s not that I feared dying at the time, I was mostly afraid of not being able to stop and start when I wanted to. I recognized that once the roller coaster left the starting point, it was designed to keep going and increase speed at as it left the heights and plunged to the ground below. I would keep that fear for many years until someone close to me shamed me into riding a monstrous upside-down coaster in California when they were just being launched. I learned that if you exhale with all of your soul on the way down and just enjoy the feeling, it was a pretty pleasurable.

Part of my fear of not being in control is probably due to the time my brother and his friends locked me in a trunk in our basement. It was a sturdy old steamer trunk and had a locking mechanism on the outside. Once someone went inside, the others would lock it. The first boy was an example and quickly let out. They I was conned into climbing in. And they locked it and left me. I can hardly describe the panic I felt when my shouts and later screams went unanswered. I paid my brother back when they finally let me out and he still bears that scar today.

When I ended up in the navy and they asked me if I wanted to go on submarines, I had to overcome my childhood fears of being confined. The extra money was the initial incentive but truthfully, I was ripe for adventure at the age of seventeen. My academics in high school were pretty abysmal do this seemed to be a way to get away from home and from life working in a steel mill or mine. I have to admit, working in a coal mine was an even greater fear than going on a submarine. Dad had taken us down into exhibition coal mine and the dirty black roof was inches away from your head as you rode the cars deep into the earth. I do not know how my great grandfather managed.

My first submarine was built around the time that I was in kindergarten. She was a converted fast attack that had been cut in the middle to accommodate sixteen missile launchers and the various equipment needed to support the weapons. You could see how awkward she was compared to submarines that were later built from the keep up to achieve the missions we went on. By the time I sailed on board, she was about thirteen years old. By today’s standards, that is not old at all. But she had some places that leaked rather significantly if you went too deep.

She was modified after the loss of the Thresher using technology that was developed to counter some of the things that the navy suspected caused the Thresher’s loss. Our emergency blow system was backfitted to be much stronger and remote closing devices for key systems were added. But no system is perfect and much of the systems still relied on well trained men to react in ways that required precision and incredible skill.

From my first patrol, I had dreams.

The dreams were pretty vivid and realistic. I had seen every World War 2 submarine movie ever made and many post-World War 2 movies. But nothing prepares you for the first time the boat submerges. I was in the control room where the whole evolution is directed from and all communications were relayed back to the Officer of the Deck.

On the surface at sea, a submarine rocks with the waves. But once you go under, that slows down the boat plunges deeper and deeper. You know that because of the glowing gauges that indicate depth and angles. On the first dive, its pretty controlled. Various stations throughout the ship monitor for leakage or improperly set valves. Once the OOD has assurance that all is in accordance with the dive procedures, the fun begins. Deep dives, angles and dangles, sudden turns and so on are used to make sure everything is stowed for sea.

To a nonqualified newbie on their first dive, every sound and creak and groan can be challenging. The trick is to never let it show. The older men had probably warned you to keep it inside or risk getting hazed. The subtle message that goes along with that is to bury any fear you had as deep inside as you could. I am not a psychologist by any means but took enough psych classes as part of my degree program to know that suppressing things like fear instead of addressing it can cause unanticipated outcomes.

I’ve shared some of my craziest patrol stories on the blog in other posts. But not the dreams. Now that I am too old for it to matter, I feel safe enough telling them. After all, who is going to haze a seventy-one-year-old man?

The first dream is reoccurring. I am asleep in my rack and the general alarm goes off. I wake up and jump out of the rack into my poopie suit. That is the name for the blue coveralls we all wore underway. The red lights in berthing are on but no one else is moving. I rip open some of the curtains on nearby bunks and no one is in any of the bunks. The first thing I think of is that I slept through the alarm. So, I race up the ladder to the mess decks. No one is there either. The hatch to the torpedo room is closed and dogged down. I can’t open it. SO, I move quickly up the ladder to the control room. It is empty too. The boat is completely empty. And looking at the depth gage, it is sinking. Fast. I get in the planes man’s seat and try to pull the planes to full rise. It does not work. All I can do is sit and watch the depth gage go deeper and deeper.

There were other dreams but that is for another time. Eventually I always woke up. I have not had that dream for a few years. But I really resisted telling any of my shipmates.

I didn’t want them to think that I was afraid. It goes with our culture.

I remember from submarine school that eventually, the hull will crush. All I can do is sit and wait. It is a fear that I have heard from many others along my journey.

Frank W. Crilley’s story

Recently I have been researching a Medal of Honor Awardee named Frank William Crilley. Frank was a Chief Gunner’s Mate (he later would become a Warrant Officer retiring as an Ensign). His background was that he was not a navy submariner, but would become one of the most prolific divers in his time of service. Of all of his actions, the first one was the one that put his name in the record books. When Navy Ensign Frank William Crilley joined the service, he likely didn’t realize he would become the hero of some of the country’s most dramatic undersea rescue and salvage operations of the 20th century. Crilley joined the Navy at just 16 years old in March 1900. It is noteworthy that he joined the navy a month after the navy purchased its first submarine. The master diver excelled in his craft, broke records and earned both the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross along the way.

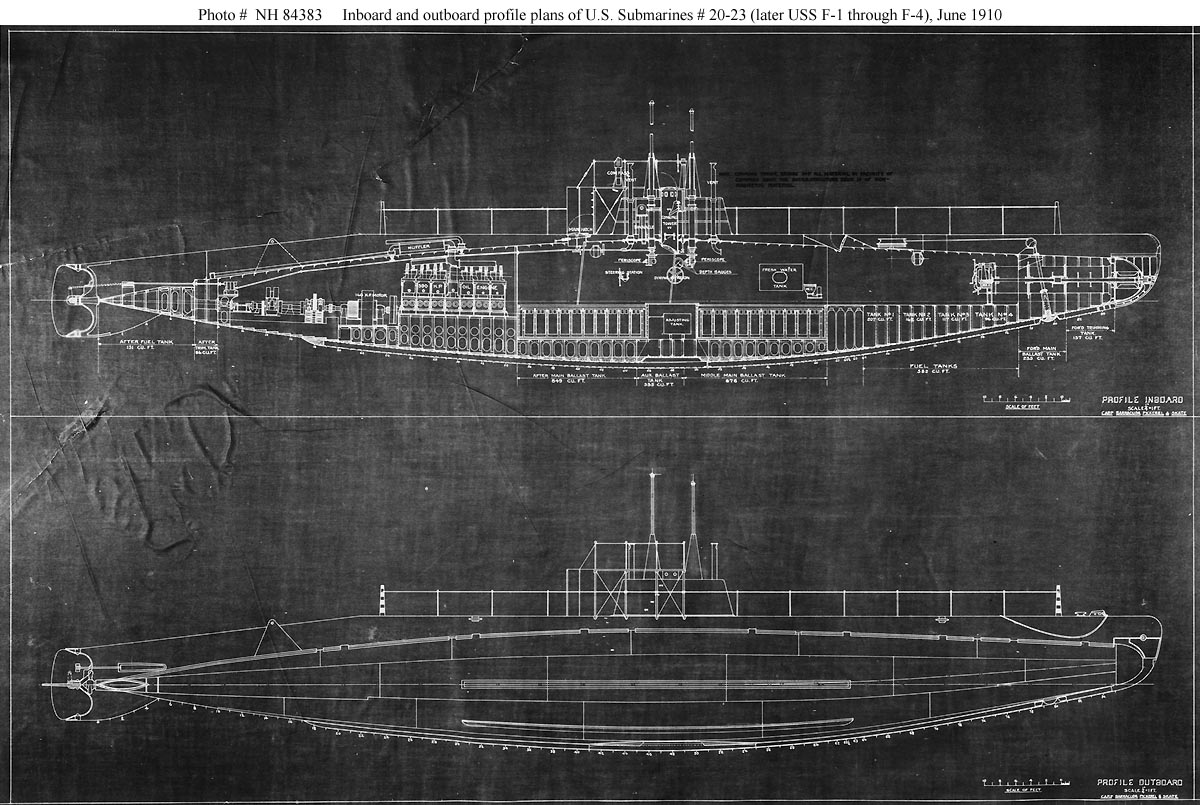

In the early days of submarines, there were a number of accidents that showed how primitive the technology was at the time. Most submarines were built using technology that was still far from advanced. The submarine F-4 was a good example of that.

On March 25, 1915, the submarine USS F-4, which was one of the first to be assigned to the new naval facilities in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, disappeared while on patrol off Honolulu’s harbor. Officials eventually determined that its battery tank corroded, causing the commanding officer to lose control of the ship. It sank about 1.5 miles off Fort Armstrong in about 300 feet of water, killing all 21 sailors aboard.

The following representation of what happened to the F-4. I say representation because to the best of my knowledge, every sailor on board was killed in the crash. The details are pretty descriptive so I can imagine it was written by a submariner.

F-4’s Last Dive

On Thursday, March 25, 1915, F-1, F-3, and F-4 went out to sea for routine diving exercises. Just beyond the Quarantine Wharf, while moving out into Honolulu’s outer harbor and Mamala Bay, Lt. j.g. Alfred Ede, in command of F-4, attempted a dynamic dive, i.e., submerging while making forward headway. He was proud of his crew’s ability to coordinate the new procedures that transferred the submarine from a diesel-powered surface ship to a submerged, battery-powered, and lethal warship in just a few minutes.

That morning, the submarine flotilla’s tender, Alert, left the floating drydock of the Inter Island Steamship Company, delaying F-4’s departure. A month earlier, F-4 was in the same dock getting new high-pitch propellers, which reduced vibration problems by permitting top speed at lower engine RPM. On this morning, as F-4 proceeded out of the harbor and passed the outer buoy at a periscope depth, she encountered F-1 coming in to port. It was 0925. As Lt. Ede observed Ens. Harry Bogusch on F-1 through the periscope, Bogusch doffed his cover as he watched a well-trimmed F-4 going out to sea. A mile west of the outer buoy Lt. F.W. Scanland, commanding F-3, waited for F-4 to clear the area before coming in to port. However, he never caught sight of F-4 departing the harbor, so F-3 returned to port by 0945.

What subsequently happened on F-4 is somewhat conjectural, but it is based on physical evidence reviewed by the board of inquiry after the boat was salvaged. Just as she was passing the outer buoy, with Lt. j.g. Ede taking the boat gradually to a depth of 60 feet, traces of chlorine gas stung the noses of the crew in the middle – or control – compartment, and F-4 overshot her target depth. Apparently, a significant quantity of seawater had reached the battery spaces.

The presence of chlorine gas caused Ede to order procedures immediately to bring the boat to the surface and into shallow water. The diving planes were set to rise, and the helmsman was ordered to make a 10-degree turn to starboard to take the boat into the shoal waters southwest of Sand Island. The starboard motor was stopped and the port motor run at top speed until apparently it overheated and burned out an armature coil,2 shutting the motor down. Both motors had a tendency to run hot, and the fact that the new propellers drew more current for the same thrust as their older counterparts, added to the problem. With enough headway, the diving planes could have counteracted the negative buoyancy caused by the flooded battery wells, but when propulsion and forward headway was lost, the extra weight of water was sufficient to drag the boat down.

In the middle compartment, several crewmembers were apparently overcome by chlorine gas and the rest retreated to the engine room after manually tripping the automatic blow, which would direct air from the high-pressure air bank to the after, middle, and forward main ballast tanks. As the crewmembers vacated the middle compartment, they secured the bulkhead door behind them.

Because of a delay in expelling ballast, increasing depth caused water to flood into the boat faster than blowing could expel it, and the submarine bottomed at a depth of 300 feet. There, the water pressure caused a line of rivets on the torpedo hatch doubler plate to fail, permitting the forward two compartments to flood rapidly. Consequently, the engine room bulkhead could not withstand the hydrostatic pressure and collapsed, flooding the engine room and drowning all within.

Breaking a Deep-Sea Diving Record

The salvage operation would prove difficult because no one had ever raised a ship from those depths before. According to an issue of the Navy’s All Hands Magazine, there were few deep-sea divers at the time, and escape and salvage equipment tailored for submarines didn’t yet exist.

Regardless, within a few days of the sub’s sinking, the Navy put together a team to try to salvage it. Five members of the service’s experimental dive team — G. D. Stillson, Frederick Neilson, Stephen Drellishak, William Loughman and Crilley — arrived in Honolulu on April 14. Specialized dive gear, a recompression chamber and a diving physician came with them. The team had been experimenting with deep sea diving off the coast of Long Island, New York, prior to being called into action.

Two days later, Crilley made the first dive of the operation and found the ship at about 305 feet below sea level — a deep-sea diving record that stood for 25 years. Crilley noticed that the ship was still upright, but giant cables would have to be fastened around it to eventually lift it and move it to shore.

According to All Hands Magazine, it was a tedious job; to get 20 minutes of dive time at 300 feet, about three hours were required for the descent and ascent. Deep water divers need to descend slowly to allow air spaces, such as in the ears and mask, time to equalize to the pressure changes. Slow ascents are required, too, because divers can build up nitrogen in their tissue due to breathing pressurized air. A slow return to the surface gives the body time to eliminate that nitrogen and reacclimate without risking decompression sickness.

Saving a Friend

On April 17, the second day of the operation, the situation became perilous. Loughman had been working on one of the cables before starting his ascent back to the surface. At a depth of about 275 feet, he paused to rest beside the cable. Around the same time, a ground swell caused the cable to jerk and smack into him, fracturing his hip. Loughman managed to cling to the cable, but his lifeline and air hose became so badly tangled in the cable that he wasn’t able to free himself. He was trapped.

When the men on the surface realized what had happened, Crilley immediately volunteered to help his comrade. Despite still recuperating from his own deep dive just two hours prior, Crilley put his diving suit back on and started to descend. When he reached Loughman’s level, Crilley asked if he could transfer his own lifeline to the injured diver. That idea was quickly shot down, so Crilley had to instead go back to the surface — much faster than a diver usually would — to get another line. He then went back down to attach it to Loughman. Once the line was secure, Crilley loosened up Loughman’s tangled lines as the crew pulled the injured man back to the surface.

Loughman, who had been stuck underwater for four hours, survived the ordeal. He had to spend nine hours in a recompression tank and several months in a hospital, Navy records showed. Crilley struggled upon his return to the surface, too, but was rehabilitated after a few hours of recompression and was able to continue with the mission.

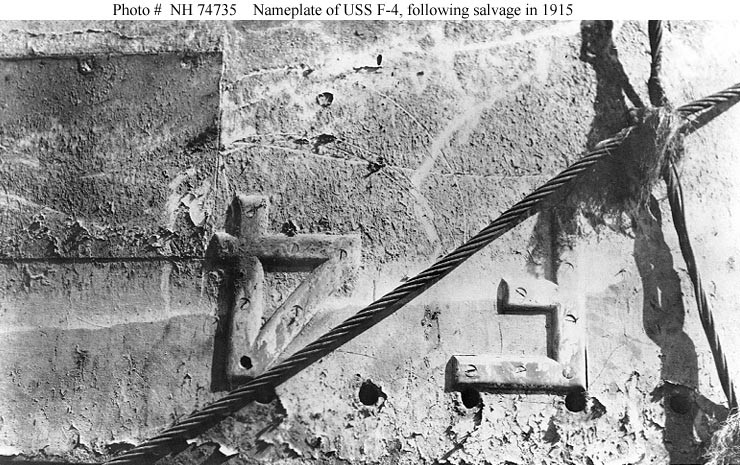

It took several more months for the F-4 to be salvaged. It was finally raised by specially constructed pontoons on Aug. 29, 1915, and towed to Pearl Harbor.

Crilley’s lifesaving actions earned him high praise, including the Silver Lifesaving Medal, which was issued to him by the Coast Guard in April 1916, according to the Philadelphia Public Ledger.

It took 13 more years for him to be nationally recognized with the Medal of Honor, which he received on Feb. 15, 1929, from President Calvin Coolidge during a White House ceremony.

Conflict/Era: Interim 1915 – 1916

Unit/Command: Navy’s Experimental Diving Team

Military Service Branch: U.S. Navy

Medal of Honor Action Date: April 17, 1915

Medal of Honor Action Place: off Honolulu, Hawaii Territory, USA

Frank William Crilley Citation

For display of extraordinary heroism in the line of his profession above and beyond the call of duty during the diving operations in connection with the sinking in a depth of water 304 feet of the U.S.S. F-4 with all on board, as a result of loss of depth control, which occurred off Honolulu, T.H., 25 March 1915. On 17 April 1915, William F. Loughman, chief gunner’s mate, U.S. Navy, who had descended to the wreck and had examined one of the wire hawsers attached to it, upon starting his ascent, and when at a depth of 250 feet beneath the surface of the water, had his lifeline and air hose so badly fouled by this hawser that he was unable to free himself; he could neither ascend nor descend. On account of the length of time that Loughman had already been subjected to the great pressure due to the depth of water, and of the uncertainty of the additional time he would have to be subjected to this pressure before he could be brought to the surface, it was imperative that steps be taken at once to clear him. Instantly, realizing the desperate case of his comrade, Crilley volunteered to go to his aid, immediately donned a diving suit and descended. After a lapse of time of two hours and 11 minutes, Crilley was brought to the surface, having by a superb exhibition of skill, coolness, endurance, and fortitude, untangled the snarl of lines and cleared his imperiled comrade, so that he was brought, still alive, to the surface.

More about the F-4 sinking and recovery here: https://theleansubmariner.com/2022/03/03/the-final-dive-of-the-f-4-march-1915/

Becoming a Legend

After the life-saving incident with Loughman, Crilley continued to make a name for himself in the diving world. In 1917, he was appointed to the rank of chief warrant officer, and about a year later, he became an ensign in the Naval Reserve. He commanded the USS Salvor in 1919 before leaving active duty in July of that year. In the mid-1920s, he was involved in the salvage of USS S-51, which sank in 1925.

By 1928, Crilley had returned to active duty for a mission that would earn him the Navy Cross. He was brought back in to work on the recovery of the submarine USS S-4, which sank as the result of a collision off the coast of Provincetown, Massachusetts, on Dec. 17, 1927. In the months that followed, Crilley made several treacherous descents into the icy waters of the Atlantic to prepare the vessel to be raised, which finally happened on March 17, 1928.

Navy Cross citation 1927-28 USS S-4 (SS 109)

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Chief Gunner’s Mate Frank William Crilley, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and fearless devotion to duty during the diving operations in connection with the salvage of the U.S.S. S-4, sunk as a result of a collision off Provincetown, Massachusetts, 17 December 1927. During the period 17 December 1927 to 17 March 1928, on which latter date the ill-fated vessel was raised, Chief Gunner’s Mate Crilley, under the most adverse weather conditions, at the risk of his life, descended many times into the icy waters and displayed throughout that period fortitude, skill, determination and courage which characterizes conduct above and beyond the call of duty.

According to various newspapers, Crilley left active duty again around 1930 but remained in the fleet reserve doing dive missions. This included a stint as the master diver on the submarine USS Nautilus as it embarked on a 3,000-mile journey to the North Pole in 1931. According to All Hands Magazine, famed explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins credited Crilley’s dives on that expedition for much of its scientific accomplishments.

Crilley was also part of the salvage work done on the presidential yacht USS Mayflower, which sank in 1931. He had his name transferred to the retired list in May 1932 but was called up by the Navy again in 1939 to help with the salvage of the USS Squalus. In 1931, Crilley served as second officer and master diver during the Arctic expedition of the civilian submarine Nautilus (previously known as USS O-12). Also in 1931, he assisted with the salvage of USS Mayflower (PY-1). Transferred to the retired list in May 1932, he was again employed on Navy work in 1939, during the salvage of USS Squalus (SS-192).

Outside of his dive career, Crilley raised a family. He married Gertrude Kelly in 1914, and they had two children together, Frank Jr. and Mary. Gertrude died in 1926, which led Crilley to eventually get remarried to Anne Moody.

Crilley died at age 64 on Nov. 23, 1947, at the Brooklyn Naval Hospital. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Crilley is remembered as a pioneer of naval diving.

After reading his story and seeing the many ways he touched early submarine salvage, I can fully understand why he was so revered for his work.

I am actually surprised that his story has so rarely been told.

Mister Mac

I’m not sure anyone who has done what you have done could honestly claim to have never had “the dream”. Each of us had similar, yet uniquely different experiences, so each would likely have had a different version of “the dream” that no verbal or written communication could adequately convey. I am reminded of a quote from the movie “Uncommon Valor”…

Col. Cal Rhodes: You know, for years, I couldn’t sleep after Korea. My nightmares all had to do with the Chosin Reservoir. The ground there was so frozen, we couldn’t bury our dead. We had to pile ’em on trucks and lash them up against the tanks. For years I’d wake up with those dead, frozen faces staring at me.

Wilkes: Did it ever go away?

Col. Cal Rhodes: No… I finally made friends with them, though.

ICFTBMT1(SS) Maxey, USN (retired)

Thanks for the post on Frank Crilley. Frank was my great uncle on my Mother’s side Frank served with his brother John and his brother Lawrence, my grandfather. All three were Navy divers. For a time they all served in Newport, RI, together. My grandfather Lawrence served on the USS Narwhal, his Lt and friend was Chester Nimitz.

You are welcome. His story is under-told in my humble opinion. I was glad to feature him

Mac

Thank you for this post! Frank Crilley was my Great-grandfather. My daughter is preparing a report on his legacy and we came across your post.

You are welcome. He was a great hero for his time

Bob