“Air Conditioning? Real Submariners Don’t Need No Air Conditioning”

From the very beginning of the submarine service in the United States,

there were a number of constants.

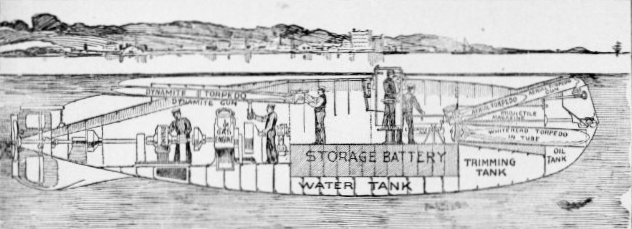

First, there was limited space. Priority was given to the machinery and support systems that would make the submarine effective. The engines were small at first but grew as the need for increased speed became apparent. The same can be said about the weapons and later electronics that would be needed to make the submarine more deadly. Finding space for the men who would operate them was almost an afterthought.

Second, the environment would suck. The early boats were gasoline powered so the smell of gasoline would permeate everything and often cause breathing problems. Add to that the noxious smells that developed from charging batteries and you had an unholy mix. The introduction of diesel oil and engines would alleviate some of that but only to a point that it would be more tolerable. Endless experiments were made in ways to filter and alleviate the odors, but the larger engines made complete elimination impossible.

Another part of the environment that was constant was the heat. Whether the heat came from the equipment or from the outside environment, life inside a steel tube was just going to be miserable much of the time. The fact that submarines were being sent far into the southern hemisphere and into the far east made the situation more miserable. The men who lived inside would just have to get used to the stench of the combined smells of sweat and body odor along with the ever-present fuel smell.

SO it was that from 1900 to about the mid 1930’s, submariners just grew a tough skin when it came to the atmosphere in their steel coffins.

Then something changed.

1935 – In spite of the difficulty in finding space, the importance of submarine operations in the Pacific, Caribbean, and South Atlantic leads the Navy Department to install the first submarine air-conditioning system on board Cuttlefish.

Blasphemy!!! Air Conditioning???

I can almost hear the seasoned old and grumbling about this new-fangled notion of conditioned air. It’s been the same throughout our submarine history that the shared sacrifices of the previous generation made them unique and somehow “better” than those who followed behind. Ask any diesel boat sailor and you will get blasted with DBF until your ears bleed.

“Back in my day, we were real submariners.” And so it goes.

I was never on a diesel boat although my last ship (USS Hunley) had six main diesels and four auxiliary diesels. The enginerooms were pretty noisy under full speed and they were certainly hot. But I get the pride of ownership and special nature of what my diesel boat brothers did.

In 1935, habitability was becoming more important for the service.

Since earlier boats had already been serving in the tropics in places like Panama, reports about effectiveness and efficiency were probably already becoming more pronounced at all levels. Panama can be unmercifully hot and humid under any circumstances and operating an R boat had to have added to the misery of the crews. Since submarines were strategically poised to protect the canal zone because of the flexibility and lethality, it made perfect sense to look for solutions.

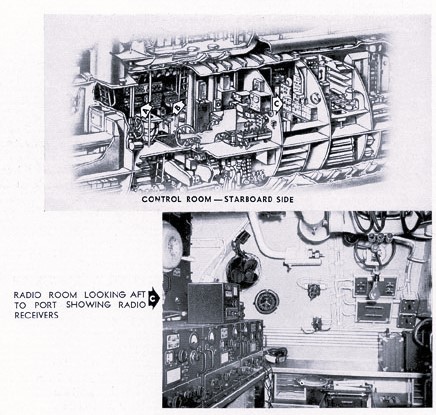

The far east was also one of the great reasons to come up with alternatives. It is a well-known fact that equipment, specifically electronic equipment needed a stable environment for maximum efficiency. Increasing dependency on radios and early forms of sound detecting equipment that would lead to advanced sonars meant that conditioned air would be critical.

So, a decision was made to place air conditioning on the Cuttlefish.

The USS Cuttlefish (SS-171) launched 21 November 1933 by Electric Boat Co., Groton, Conn.; sponsored by Mrs. B. S. Bullard; and commissioned 8 June 1934, Lieutenant Commander C. W. Styer in command.

Departing New London 15 May 1935, Cuttlefish arrived at San Diego 22 June. She sailed on torpedo practice and fleet tactics along the west coast, as well as in the Hawaiian Islands, until 28 June 1937 when she sailed for the Panama Canal, Miami, New York, and New London.

Arriving at New London 28 July 1937 she conducted experimental torpedo firing, sound training, and other operations for the Submarine School. She sailed from New York 22 October 1938 for Coco Solo, C.Z., where she conducted diving operations and other exercises for the training of submariners until 20 March 1939, sailing then for Mare Island.

Cuttlefish arrived at Pearl Harbor 16 June 1939 and was based there on patrol duty, as well as joining in battle problems and exercises in the Hawaiian area. That autumn she cruised to the Samoan Islands, and in 1940 to the west coast. On 5 October 1941 she cleared Pearl Harbor for an overhaul at Mare Island, enemy plane caught her on the surface and dropped two bombs as she went under, both of them misses.

As it became obvious that the Japanese Fleet was out in strength, Cuttlefish was ordered to patrol about 700 miles west of Midway, remaining on station during the Battle of Midway of 4 to 6 June 1942. She returned to Pearl Harbor 15 June, and there and at Midway prepared for her third war patrol, for which she sailed 29 July. Patrolling off the Japanese homeland, she attacked a destroyer on 18 August, and received a punishing depth charge attack. Three days later she launched a spread of torpedoes, three of which hit a freighter and one of which hit an escort. Explosions were seen, but the sinking could not be confirmed. On 5 September she attacked a tanker which, it is believed, she sunk.

Returning to Pearl Harbor 20 September 1942, Cuttlefish was ordered to New London, where she served the Submarine School as a training ship from December 1942 until October 1945. She was decommissioned at Philadelphia 24 October 1945 and sold 12 February 1947.

Cuttlefish’s third war patrol was designated as “successful,” and she received one battle star for that patrol and one for her service during the Battle of Midway.

The Gato Class

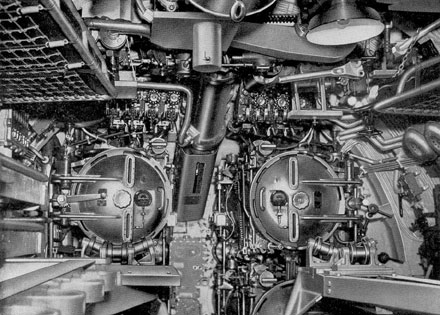

The class of ships had numerous crew comforts including showers, air conditioning, refrigerated storage for food, generous freshwater distilling units, clothes washers, and bunks for nearly every crew member; these were luxuries virtually unheard of in other navies. The bureau designers felt that if a crew of 60–80 men were to be expected to conduct 75-day patrols in the warm waters of the Pacific, these types of features were vital to the health and efficiency of the crew. They could be added without impact to the ship’s war fighting abilities due to the extra room of the big fleet ship.

The air conditioning in particular had a very practical application, too, besides comfort. Should a submarine submerge for any length of time, the heat generated by the recently shut-down engines, electronic gear, and 70 warm bodies will quickly raise internal temperatures above 100 °F (38 °C).

High humidity generated by tropical waters will quickly condense and begin dripping into equipment, eventually causing electrical shorts and fires. Air conditioning, acting mostly as a dehumidifier, virtually eliminates this problem and greatly increases mechanical and electrical reliability. It proved to be a key factor in the success of these ships during World War II.

From a navy manual on engineering:

13A3. Purposes of air-conditioning. Apart from this merely mechanical reaction, considerations of health, efficiency, and morale require that the air should be fit to breathe. This necessitates, among other things, the removal of fumes from a ship’s galley, engine room, battery room, and water closets. Stale air must then be replaced by fresh air. Moreover, the body gives off excess heat and moisture by means of the air that is breathed and the air in contact with the surface of the body. It becomes obvious, therefore, that proper air-conditioning within the enclosed quarters of a ship is important, and that during the long dives of a submarine it is of even greater importance.

Air-conditioning is also needed for the protection of equipment, especially electrical apparatus. The large amount of moisture in the air given off daily from the bodies of the crew, from cooking, batteries, and bilges, would condense on any cool surface if it were not removed by air-conditioning. This moisture is extracted from the air by the air conditioning equipment and is run into a tank. It is not suitable for drinking, cooking, or bathing, but is suitable for the washing of clothes.

From an article in the Washington Post in 1977:

World War II Submarine Life:

By Joseph P. Mastrangelo

February 5, 1977

The words “Cold,” “Energy” and “Conserve,” are on everyone’s lips, making most of our conversations sound like the opening act of Thornton Wilder’s play, “The Skin of Our Teeth,” as the Antrobus family lives through the ice age.

The situation is a serious one, but if President Carter, a former submariner, remembers some of the conservation efforts put forth by submarine personnel during long patrol runs and puts them to use, America should pull out of it.

A submarine leaving port and headed for a station thousands of miles from a friendly harbor is a lonely, self-contained unit.

In World II, when the order “Rig Ship For Sea” came over the loudspeaker it mean 70 to 80 days of confinement and excitement, but also an extreme curtailment of the comforts of everyday life for the officers and crew.

Water had the highest priority. Making fresh water from sea water meant running it through a condenser situated in the lower flat of the engine room. This process used up electricity that was being generated by an auxiliary engine, which needed precious fuel to operate.

As a result, we only had one shower a week. But even that was cut back.

When loading the sub for sea, every available space was used for storing food and water and whatever else was necessary for the long sea voyage.

The chief steward always found the crew’s showers a good place to store his sacks of potatoes. Most of the crew liked potatoes so no one really minded. We would only walk around smelling ripe for a few weeks until the potatoes were eaten and then we could get back to cleaning up.

The engine room crew responsible for the fresh water were the conservative users of it and watched other crew members with a wary eye at all times. One quart of water a day was allowed for each sailor to do with as he pleased.

The spigot in the crew’s mess that was a grab-a-mouth-of-water-as-you-pass-by fountain, had three holes to sip from. Late one night when most of the crew were sleeping two of the holes were soldered shut.

A fireman whose shut it was to convert salt water to fresh also took an extreme measure to conserve water. It happened one day when he had been putting in more time than he thought he should down by the condenser.

A few days before, a lookout had reported a school of dead fish floating on the surface and we sailed right through it.

The fireman borrowed some hamburger from the cook and when most of the crew were eating, he brought the salt water intake strainer into the mess with a blob of hamburger on it and made sure everyone got a look at it.

There was little water used for next few days.

If the enginemen were tough on conserving their section of energy, the electricians fought back harder to conserve a lot of time on battery charges.

The first piece of comfort equipment to disappear was the sun lamp.

Then all the little fans that provide a tiny breeze while you slept disappeared.

Light bulbs were next, until it became so dark in some parts of the sub that we began carrying flashlights.

The ship’s cooks got sore at the enginemen for the chintzy water supply and at the electricians for the bulb and fan snatching and began to prepare exotic meals such as baked stuffed sardines and a few other highly indigestible dishes.

On each patrol run a sailor would get the laundry concession and be able to pick up some extra money. The laundry sailor got angry at the electricians for pulling the plug once in a while when his machine was churning away and at the water makers who complained that he was using too much water.

He fired back by turning out of a wash that gave us a tattletale dark gray look.

Hand-lettered signs would go up all over the place urging others sailors to take it easy on the water and electricity. One such sign hanging from a bulb asked, “Why is this bulb left burning all the time?” Under it in a scrawl was the answer, “Because it’s our only source of heat.”

Actually, heat was no problem in the South Pacific, but air conditioning was important, although it was a high user of energy. Even the electricians avoided fooling with that.

Toward the end of the patrol run the officers’ shower nozzle disappeared, but they didn’t complain much.

Things would ease up when we were ordered back to port, and we knew we could get a second shower that week. Even the cooks would get generous with the meals they had been holding back from us.

It was always a good feeling, tying up at the pier and walking around topside, all of us pale and smelly as we watched the relief crew attaching fresh water and electricity from the pier.

We ate heads of fresh lettuce, bowls of ice cream, and read our three-month-old mail, most of which started with, “You should be happy to be where you are, it’s freezing back here -”

After reading that article, I realized that not much changed in my generation.

Modern Boats

I grew up in a time when nuclear power boats were replacing diesel boats in both number and missions. Our boats could operate submerged for months at a time without surfacing. Advances in air conditioning along with atmosphere control made the boats much more habitable. I have studied the newest generation of boats, but I can only imagine that our older boat would pale in comparison. The technology is phenomenal, and I am jealous of the men and women who get to operate them.

There are some great articles about what could happen today if there was a catastrophic failure of the air conditioning systems on submarines. One of those is here:

From the article:

A combination of high air temperature, high humidity, thermal radiation (from the sun and boat surfaces) and low air movement contribute to heat stress. The loss of AC on a boat in tropical environments could very quickly result in these conditions. If there is no decrease in crew physical activity, then heat illness casualties would quickly present to the medical team. As the whole ship’s company will soon be experiencing similar conditions, waiting for the first casualty to occur is likely to lead to multiple simultaneous heat injuries. Heat injuries are more likely to occur first in occupations with a higher thermal load such as engineers or cooks, but are often masked in fit, healthy individuals who are highly motivated and focused on their task. This makes predicting exactly who will be affected and when they will reach their limit very difficult.

I have been on earlier boats that suffered loss or lowered capacity for air conditioning for a number of reasons. It definitely left me with many unpleasant memories.

But there is still one thing I am curious about.

Despite massive improvements in my generation in all areas, the smell of your clothes once you returned from a 60- or 90-day run was horrendous. I have visited a number of diesel boat museums and once you go below the upper deck, that same smell comes back. It’s like stepping into a time machine. The last time I was on the Requin in Pittsburgh, I came home, and my wife said “You need to change clothes. You smell like submarine.

We have several members of our local USSVI chapter who are ‘real’ submariners (DBF!), one of whom was a WW2 sub sailor. All of us (and our wives!) agree that the advancement in technology has not abrogated the “…smells like a submarine…”