October 1943 was a very busy time for an expanding fleet in every corner of the world.

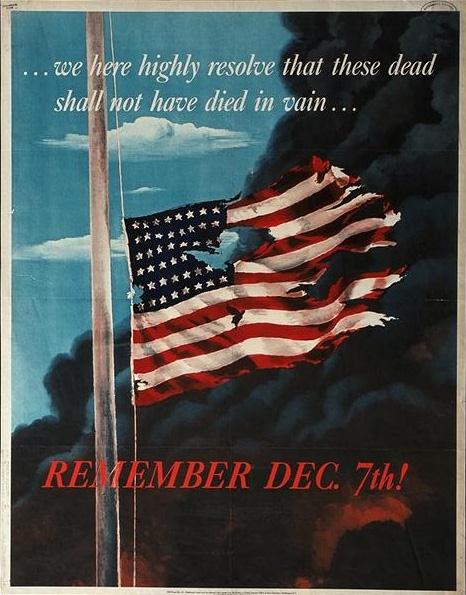

The trials for the leadership of the Navy and Army that had been in charge during the attacks on Hawaii and elsewhere were finally getting under way. Less than two years after that disastrous day, many people were still seeking answers about how what should have been an invincible fleet was caught so off guard.

Some notes from the official history of that day record just how devastating the attack was and how costly:

ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR AND WAR – DECEMBER 1941

Sunday, December 7, 1941

Japanese planes torpedo and sink battleships Oklahoma (BB-37) and West Virginia (BB-48), and auxiliary (gunnery training/target ship) Utah (AG-16). On board Oklahoma, Ensign Francis G. Flaherty, USNR, and Seaman First Class James R. Ward, as the ship is abandoned, hold flashlights to allow their shipmates to escape; on board West Virginia, her commanding officer, Captain Mervyn Bennion, directs his ship’s defense until struck down and mortally wounded by a fragment from a bomb that hits battleship Tennessee (BB-43) moored inboard; on board Utah, Austrian-born Chief Watertender Peter Tomich remains at his post as the ship capsizes, securing the boilers and making sure his shipmates have escaped from the fireroom.

Japanese bombs also sink battleship Arizona (BB-39); the cataclysmic explosion of her forward magazine causes heavy casualties, among them Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, Commander Battleship Division 1.

When Arizona explodes, she is moored inboard of repair ship Vestal (AR-4); the blast causes damage to the repair ship, which has already been hit by a bomb. Only the skill and nerve of Commander Cassin Young and his crew would prevent the loss of the Vestal. He would receive the Medal of Honor for his heroism. The Vestal would sail on through the end of the war providing needed repairs as the stricken navy battled back against the Japanese.

Battleship California (BB-44) is hit by both bombs and torpedoes and sinks at her berth alongside Ford Island;

Japanese bombs damage destroyers Cassin (DD-372) and Downes (DD-375), which are lying immobile in Drydock No. 1.

Minelayer Oglala (CM-4) is damaged by concussion from torpedo exploding in light cruiser Helena (CL-50) moored alongside, and capsizes at her berth; harbor tug Sotoyomo (YT-9) is sunk in floating drydock YFD-2. ….. Of the other sunken ships, California, West Virginia, Oglala, and Sotoyomo are raised and repaired; Cassin and Downes are rebuilt around their surviving machinery; all are returned to service. Oklahoma, although raised after monumental effort, is never repaired, and ultimately sinks while under tow to the west coast to be broken up for scrap. The hulks of Arizona and Utah remain at Pearl as Memorials.

Battleship Nevada (BB-36), the only capital ship to get underway during the attack, is damaged by bombs and a torpedo before she is beached.

Battleships Pennsylvania (BB-38), Tennessee (BB-43), and Maryland (BB-46), light cruiser Honolulu (CL-48), and floating drydock YFD-2 are damaged by bombs; light cruisers Raleigh (CL-7) and Helena (CL-50) are damaged by torpedoes; destroyer Shaw (DD-373), by bombs, in floating drydock YFD-2; heavy cruiser New Orleans (CA-32), destroyers Helm (DD-388) and Hull (DD- 350), destroyer tender Dobbin (AD-3), repair ship Rigel (AR-11), and seaplane tender Tangier (AV-8), are damaged by near-misses of bombs; seaplane tender Curtiss (AV-4) is damaged by crashing carrier bomber; garbage lighter YG-17 (alongside Nevada at the outset) is damaged by strafing and/or concussion of bombs.

Carrier Enterprise (CV-6) Air Group (CEAG, VB 6 and VS 6) search flight (Commander Howard L. Young, CEAG), in two-plane sections of SBDs, begins arriving off Oahu as the Japanese attack unfolds; some SBDs meet their doom at the hands of Japanese planes; one (VS 6) is shot down by friendly fire.

Navy Yard and Naval Station, Pearl Harbor; Naval Air Stations at Ford Island and Kaneohe Bay; Ewa Mooring Mast Field (Marine Corps air facility); Army airfields at Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows; and Schofield Barracks suffer varying degrees of bomb and fragment damage.

Casualties amount to: killed or missing: Navy, 2,008; Marine Corps, 109; Army, 218; Civilian, 68; Wounded: Navy, 710; Marine Corps, 69; Army, 364; Civilian, 35.

What about the submarines?

It has been said many times that the two greatest mistakes made by the attacking Japanese were timing and targets. The timing was that no aircraft carriers were present on the day of the attack. The targets include not just the aircraft carriers that were not present, but the neglect of the submarine base, the extensive oil storage facility, and the vast majority of the shipyard which suffered damage but not in a way to incapacitate it.

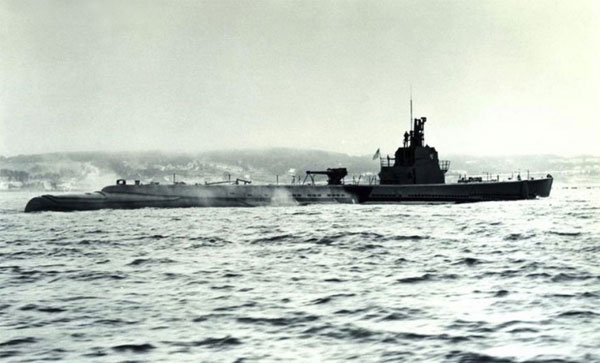

There were four submarines present at Pearl Harbor on the day of the attack. Narwhal (SS-167), Dolphin (SS-169), Cachalot (SS-170), and Tautog (SS-199). One submarine that was not present during the attack was the USS Gudgeon (SS-210). But she would be the first ship to begin a campaign of destruction against the Japanese empire which ultimately ended in Tokyo Bay.

The lightly touched submarine base would play a pivotal role in the rising tide of newer and more capable submarines that would soon reach Hawaii. Within months, these newer submarines would make an impact using a previously unthinkable type of warfare: Unrestricted Submarine Warfare.

Gudgeon Pre-war

The Gudgeon keel was laid down by the Mare Island Navy Yard. She was launched on 25 January 1941, sponsored by Mrs. Annie B. Pye, wife of Vice Admiral William S. Pye, Commander Battleships, Battle Force and Commander Battle Force. The boat was commissioned on 21 April 1941. Her construction cost $6 million.

After shakedown along the California coast, Gudgeon sailed north on 28 August, heading for Alaska via Seattle, Washington. On her northern jaunt the new submarine inspected Sitka, Kodiak, and Dutch Harbor for suitability as naval bases. Continuing to Hawaii, she moored at the Pearl Harbor submarine base on 10 October 1941. Training exercises and local operations filled Gudgeon’s time for the next two months. During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December she was at Lahaina Roads on special exercises, but returned to base immediately.

First war patrol

On 11 December, Gudgeon (commanded by Elton W. “Joe” Grenfell) departed Pearl Harbor on the first American submarine war patrol of World War II. Her commanding officer was provided with explicit written orders to carry out unrestricted submarine warfare. Gudgeon made her first contact on a target in Japanese Home Waters 31 December. When she returned 50 days later, Gudgeon had contributed two more impressive “firsts” to the Pacific submarine fleet. She was the first American submarine to patrol along the Japanese coast itself, as her area took her off Kyūshū in the home islands. On 27 January 1942, en route home, Gudgeon became the first United States Navy submarine to sink an enemy warship in World War II. Gudgeon fired three torpedoes, and the submarine I-73 was destroyed; though Gudgeon claimed only damage, the loss was confirmed by HYPO.

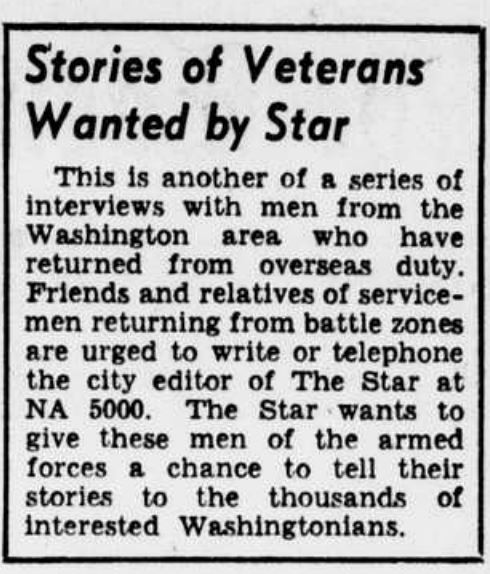

A sailor home on leave

In 1943, the public needed to know that their sons were truly making a difference. But the press struggled with operational security balanced against the public’s right to know. One of the newspapers in Washington DC found a good way to recognize the service and sacrifices by doing stories about local boys who came back from the war. One such story was about Machinist Mate First Class Charles C. Albert. He was a submariner that had come home for an “extended leave” to see his mother. While the paper does not reveal the name of the submarine he was on, a little detective work seems to indicate that he was a crew member on the USS Gudgeon.

(Note, the Gudgeon was one of three subs that left that day but the USS Pollock SS 180 did not arrive until December 9th in Pearl Harbor and the USS Plunger’s patrol schedule does not match Albert’s story. If in the future anyone finds further evidence that he served on either, I will make the necessary corrections. For now, I believe most of the evidence supports service on Gudgeon.)

Back From the Wars

Pearl Harbor Attack Sounded

Like Radio Scare to Seaman

Four days after the attack on Pearl Harbor a United States submarine slid out of the harbor on its way to complete the first successful war patrol of the war in enemy waters. It carried as one of its crew Charles C. Albert, Machinist Mate, First Class.

On the morning of the Japanese attack on the island. Machinist Albert was enjoying coffee and cigarettes in the mess hall of the submarine, which was about 20 miles out at sea. Suddenly orders were given to submerge as a strafing plane passed overhead. In the afternoon when the ship surfaced the crew began to pick up broadcasts from the mainland announcing the devastating attack.

“I thought it was just another Orson Welles affair,” Machinist Albert commented.

“And even though we were refused permission to enter the harbor that night. I didn’t believe it until we got in the next day and saw for myself.”

Preparations were made for a hasty departure and soon the submarine was on its way to an unknown destination. Six days at sea the ship’s radio was picking up the broadcasts of “Tokio Rose,” woman broadcaster on Japanese short wave, telling the American women in Hawaii how sorry the Japanese, people and government were to sink our ships and “send their poor American husbands to the deep.”

“I guess they were trying to scare us off, because we were just getting our offensive organized,” Machinist Albert remarked.

Reaching the Straits of Yokohama and the heavily mined approaches to the harbor, the submarine lay submerged by day and surfaced at night. Every four or five minutes the officer on duty hoisted the periscope to the surface, took a look around and lowered it again. About three nights later a large freighter was sighted. The submarine surfaced, fired four torpedoes and scored three hits.

The submarine frequently sank Japanese sampans, which often carried radios, deck guns and depth charges. It also bagged two smaller freighters. Operating against intensive opposition by air and anti-submarine patrols, the crew completed the mission with 16,000 tons to its credit.

Machinist Albert, who has been decorated with the submarine combat insigne for participating in several war patrols, said today that the first one was the most colorful to him. After that the crew seemed better organized and more confident, he added.

“With eight months’ submarine duty in peacetime behind me, I suddenly had to get used to the idea that we were at war and that our mission was to sink enemy ships,” he continued. “Now we pop them off like ducks in a shooting range.”

After almost three years’ duty in enemy waters, Machinist Albert says it still makes him nervous to hear the explosion of a depth charge nearby even though he knows that if a submarine is hit, the crew will never hear the explosion

As he passed Hawaii on his recent return to the United States, Machinist Albert heard again the voice of “Tokio Rose” warning American women on the island that it would be most embarrassing for them when the Japanese troops took over.”

“A lot of the fellows listened to her regularly just for the laugh,” he reminisced.

Machinist Albert, who enlisted in the Navy in 1939, hasn’t seen his mother for five years. He is spending an extended leave with her at 1229 Franklin street N.E. He is glad to have the rest but says he wouldn’t swap submarine duty for any other in the Navy.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-10-28/ed-1/seq-25/

The Gudgeon would continue her work and complete eleven war patrols. Sadly, she would never return from her twelfth. Her story is here:

http://www.oneternalpatrol.com/uss-gudgeon-211-loss.html

Searching through the records, Petty Officer Albert was not present during the last patrol. This story was written in October 1943 (dateline October 28th) and the Gudgeon was on her tenth war patrol along the China coast. It is very possible that he departed when she took on fuel at Johnston Island. He is not listed in any records as having been assigned to Gudgeon on her final patrol.

On Eternal Patrol – Lost Submariners of World War II

Following is a listing of the approximately 3630 men who are known to have been lost while in service in the US Submarine Force during World War II. In addition, about 250 men who were lost while serving on submarine tenders and submarine rescue vessels are included on this list. Every man has his own personal memorial page. Presently, over 90% of the men have photos on their pages.

http://www.oneternalpatrol.com/wwii.htm#A

As I reread the article about Alberts, I thought a lot about his statement about depth charges. In the patrols he would have participated in, Gudgeon was attacked many times. While I served on five different boats, I was never on board one that was depth charged. I can only imagine the living hell some of those boats went through. But his last statement about never hearing the one that finds you brings back one of my biggest fears from my days underway. We operated in some pretty interesting areas with lots of company. Would we have heard the one that found us?