Note: I collected much of the technical information for this story from open source documentation. As always, I do not reveal information from my actual submarine experience. I love and respect my fellow submariners still on patrol and only publish these generic submarine statistics to make a point.

Note: I collected much of the technical information for this story from open source documentation. As always, I do not reveal information from my actual submarine experience. I love and respect my fellow submariners still on patrol and only publish these generic submarine statistics to make a point.

So you were a submariner? What do you think about…..

I’m willing to bet that if you are someone who was at one point “Qualified in Submarines” and someone around you was aware that you were a submariner, you have been queried about the recent loss of the little submersible that was on its way to see the Titanic. I can assure you I have heard the same questions many times since the accident.

The whole thing has brought back many memories that have long been submerged. Even though I write stories about the boats and do a lot of public presentations, I do actually have a pretty full life even in my third retirement. Watching the news stories and understanding basic submarine engineering, I knew from the outset that chances of a rescue were infinitesimally small and even if they could reach the craft (assuming it didn’t implode) how would they be able to rescue any survivors?

When I went to submarine school over fifty years ago, we learned about all the things that could go wrong as we operated a modern submarine in a hostile environment. I was a young kid when Thresher went down but I was a news junky even at that age and had read every story that I could get my hands on. Even the loss of the Scorpion occurred before I raised my right hand. But once I joined the Navy, there was no doubt in my mind that I wanted to be a submariner.

In sub school, we learned a lot of theory and a generic submarine layout. At that point, we even had to go through submarine escape training in the old tower. It was blow and go from a lock out wearing a Steinke hood. Frankly, I was as afraid as anyone but made the descent with no problems. It wouldn’t be until I got to my first boat when I would learn that even though there were two escape trunks on the boat, no one would ever actually use them. The depths we operated in made it nearly impossible to do a free ascent so the only option was to bring the boat back to the surface. It became pretty common to understand that everyone dove together and everyone came back together.

We also learned about depth ratings.

Depth ratings are primary design parameters and measures of a submarine’s ability to operate underwater. The depths to which submarines can dive are limited by the strengths of their hulls.

Ratings

The hull of a submarine must be able to withstand the forces created by the outside water pressure being greater than the inside air pressure. The outside water pressure increases with depth and so the stresses on the hull also increase with depth. Each 10 metres (33 feet) of depth puts another atmosphere (1 bar, 14.7 psi, 101 kPa) of pressure on the hull, so at 300 metres (1,000 feet), the hull is withstanding thirty atmospheres (30 bar, 441 psi, 3,000 kPa) of water pressure.

Test depth

This is the maximum depth at which a submarine is permitted to operate under normal peacetime circumstances, and is tested during sea trials. The test depth is set at two-thirds (0.66) of the design depth for United States Navy submarines, while the Royal Navy sets test depth at 4/7 (0.57) the design depth, and the German Navy sets it at exactly one-half (0.50) of design depth.

Operating depth

Also known as the maximum operating depth (or the never-exceed depth), this is the maximum depth at which a submarine is allowed to operate under any (e.g. battle) conditions.

Design depth

The nominal depth listed in the submarine’s specifications. From it the designers calculate the thickness of the hull metal, the boat’s displacement, and many other related factors.

Crush depth

Sometimes referred to as the “collapse depth” in the United States, this is the submerged depth at which the submarine implodes due to water pressure. Technically speaking, the crush depth should be the same as the design depth, but in practice is usually somewhat deeper. This is the result of compounding safety margins throughout the production chain, where at each point an effort is made to at least slightly exceed the required specifications to account for imperceptible material defects or variations in machining tolerances.

A submarine, by definition, cannot exceed crush depth without being crushed. However, when a prediction is made as to what a submarine’s crush depth might be, that prediction may subsequently be mistaken for the actual crush depth of the submarine. Such misunderstandings, compounded by errors in translation and a more general confusion as to the meanings of the various depth ratings, have resulted in multiple erroneous accounts of submarines not being crushed at their crush depth.

Notably, several World War II submarines reported that, due to flooding or mechanical failure, they’d gone below crush depth, before successfully resurfacing after having the failure repaired or the water pumped out. In these cases, the “crush depth” is invariably either a mistranslated official “safe” depth (i.e. the test depth, or the maximum operating depth), or the design depth, or a prior—and evidently incorrect—estimate of what the crush depth might be. World War II German U-boats of the types VII and IX generally imploded at depths of 200 to 280 metres (660 to 920 feet).

It helps when you see one actully being built

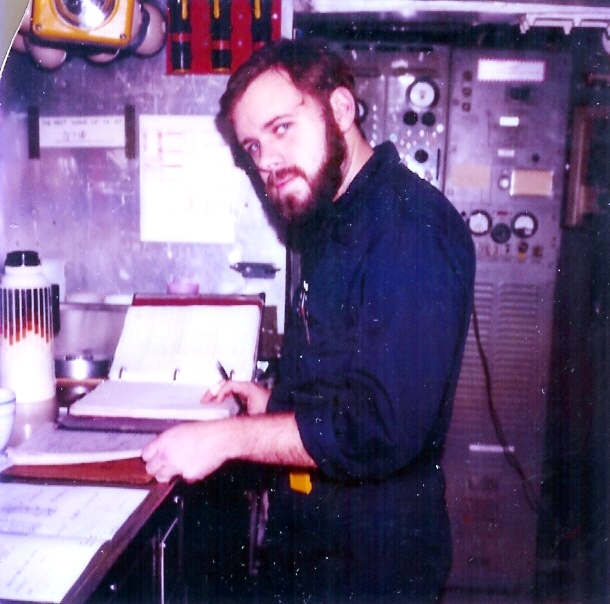

I was lucky enough to help build my third submarine at the Newport News Shipyard. The USS San Francisco was still undergoing outfitting when I reported aboard in the early days of new construction. I witnessed the construction and testing that went into the building of this sleek new fast attack submarine. I learned every system until I could see it in my mind in the dark. I knew where every single valve was located, all of the emergency equipment and devices, every power panel, and anything that could burn or leak. So did everyone else. The older guys trained the newer guys. We practiced and prepared for every single thing that could go wrong and then we practiced some more.

A submarine is the ultimate underwater weapon but so many things could go wrong. We were carrying weapons (torpedoes and other effective weapons of destruction) which involved opening large exposures to the sea. Submarines also can find themselves being chased by other submarines and ships in places we don’t discuss. So the danger is real.

Redundancy

Submarines have backups to the backups. We used to rely on hydraulics and probably still do to some extent. But we had manual devices that could be used if the hydraulics failed Sub Safe was a gift from the lessons learned from Thresher and it has probably prevented the loss of a number of submarines through the many decades since.

But submariners respect science. If you remember that you are operating at high speeds in areas where one mistake could cause a catastrophe, you are constantly aware of the depths you are traveling in. And you are also aware that even the best training in the world (and it is) can’t stop that catastrophe if the equipment or hull fails to deliver what the designers promised.

Lessons Learned

My very next ship was the USS Ohio (SSBN 726). She came on line at the same time the San Francisco did but she took forever to get out of the builders yard in Connecticut. I will not say why, but let’s just say they learned a lot about welding and quality assurance after they built her. Learning the boat as a new crew member, I could see the physical evidence of that learning. I’ll leave it at that.

We are not the same

I consider submariners some of the finest professionals I have ever met. The tremendous amount of training, devotion, continuous improvement and dedication to perfection is a hallmark for those of us who traversed beneath the ocean’s surface. With very rare exceptions, the operators remain vigilant and ready to overcome the unthinkable.

While I can feel sadness for the death of anyone, I honestly feel that the owner of the company did not learn anything from the history of submarines since 1900. That was arrogance in my opinion and it cost five people to lose their lives.

I’m typically not a big government intervention kind of guy, but I truly hope that when it comes to future submersibles, common sense overcomes profits.

This crushing depth applies to the most modern sibs…the effect on men and material occurs far before the actual sub implodes.

Mister MAC – dlo you have a source for the postcard image of the Holland sub? Or – may I have your permission to swipe it for a book I am writing?

Thanks for yolur web page – its a great resource.

Mark Newell (Lexington SC)

The Naval Heritage and History web site is the source. https://www.history.navy.mil/ As long as they are properly attributed as the source, you should be good to go

Mac