Rear Admiral Taussig and the Warning Before Pearl Harbor

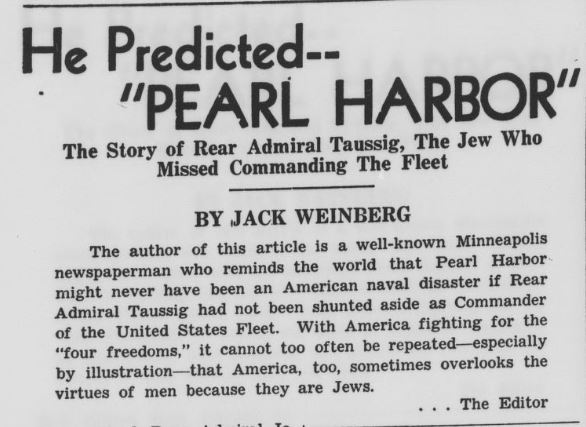

An obscure article in the Southern Jewish Weekly put forward an interesting idea in the form of an article published on January 30, 1942. In some ways, this is part three of a series about Taussig. But it casts the story in a different light and one worth examining.

American was still reeling from the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the string of defeats facing the country in the months following the initial attack. The country was getting a steady diet of defeat and destruction in faraway places like Guam and the Philippines. Blame was being cast in every direction including the military, Congressional Leaders and the President himself.

Could the attacks have been predicted? Probably. Did anyone try and tell the leadership? Most definitely.

One of those men was Rear Admiral Joseph K. Taussig.

“In May 1940, Taussig again locked horns with now-president Franklin D. Roosevelt, when Massachusetts Senator David I. Walsh invited Taussig to testify at Senate hearings on plans to expand the navy. Taussig advocated the building of Iowa-class and Montana-class battleships and offered testimony to the aggressive, imperialistic designs of the Empire of Japan that planned to annex China, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies. He warned of the superiority of the Japanese Merchant fleet to that of the US, and the need to replenish U.S. bases in the Pacific Ocean and prepare for defense of the Philippines, stating, “I cannot see how we can escape being forced into war based on the present trends of events.”

https://theleansubmariner.com/2020/12/06/the-tanaka-memorial-real-or-imagined/

https://theleansubmariner.com/2020/12/07/the-tanaka-memorial-real-or-imagined-part-2/

From the article:

Now retired, Rear Admiral Joseph K. Taussig must be thinking these days, as he reads the newspapers, how different the situation in the Pacific might have been had the Senate Naval Affairs Committee listened to his recommendations early in 1940 instead of rebuking him as an alarmist.

As it is, the Jewish navy man can take credit for the fact that the defenses at Pearl Harbor are stronger than they would have been had he not testified at the committee hearing; because it was only through his efforts that more money was finally appropriated for Pearl Harbor.

For it was Admiral Taussig who predicted the Pearl Harbor attack. In the spring of 1940 he warned that the Japanese sought virtual domination of the Far East and would even go to war to attain their aim.

The repercussions from that warning were many. Even President Roosevelt, whose disfavor Taussig had incurred, threatened to furlough the Admiral at half pay, only to be dissuaded by Admirals Stark and Nimitz, who opposed any discipline. Stark and Nimitz must have known then, as the entire country knows today, that Taussig was right. His views were the private opinions of practically every officer in the Navy. In his testimony before the committee, Taussig—whose father before him, Edward David Taussig, scion of a St. Louis Jewish family, was a Rear Admiral—urged the immediate establishment of an “impregnable” naval base in the Philippines, the strengthening of the Navy and agreement with the English, the Dutch and the French guaranteeing the safety of the Pacific.

“We need be under no delusions,” he warned the Senators, “as to the aims and policies of Japan. The pronouncements of her statesmen in answer to protests against violations of rights of other nations are, of course, worthless. The real policies of Japan are embodied in the declarations of her militarists during the past year, and it is these policies that are being carried out.”

First step in this plan by Japan was the domination of the Far East, Taussig declared then.

“When there are nations,” the Admiral continued, “who believe only in the sword to obtain what they want from others and are anxious to use it, peaceably inclined nations must go to war to defend themselves or accept domination. Such a situation exists today and I cannot see how we can escape being forced into eventual war by the present trend of events.”

Today’s headlines from Singapore, the Philippines, Pearl Harbor, Batavia, Changsha are tragic witnesses of the accuracy of Taussig’s declaration. Although he is out of the service after a long and honorable career in the Navy that dates back to the Boxer rebellion, Admiral Taussig might have been the instrument through which the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines could have been avoided.

During his Navy tenure Taussig was its star pupil and scholar.

Born in 1877 in Dresden, Germany, where his father was on duty at the time, Joseph Knefler Taussig twice won the Institute of Naval Affairs gold medal. On eleven occasions he was decorated for bravery in action. The study of the Far East was his specialty. He served valiantly in World War I and one of his statements has become a legend at Annapolis Naval Academy. In command of a destroyer squadron, Taussig was sent to Ireland shortly after American entry into the conflict.

The crossing was a hazardous one, with the Atlantic kicking up one of its toughest storms.

The British, anxious to have the squadron go into action within at least a week, asked Taussig how soon his ships could head for the North Sea for submarine duty. “Sir, we are ready now,” is reported to have been Taussig’s reply- Actually, he asked for 24 hours to take on oil and water.

Strained feeling between Taussig and Roosevelt dates back to the days when the President was assistant Secretary of the Navy. Taussig joined with the late Admiral Sims and other Navy officers in criticizing Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels and his Assistant Secretary in their prosecution of the war. Following the Armistice, Taussig even appeared before a Congressional investigating committee, testifying that the Navy Department chiefs had not taken “adequate steps to provide personnel necessary for the proper conduct of the Navy during the war.”

Roosevelt, then Democratic candidate for Vice-President, wrote a sharp letter to the Senate Naval Affairs Committee in which he denied the charges.

Just before Roosevelt became President in 1933, Taussig was named Assistant Chief of Naval Operations, a very high post. The navy man went to the President and suggested the latter might want to have another man in view of their earlier difficulties. “Forget it, Roosevelt told Taussig“

In 1936 Taussig was slated to become Commander of the United States Fleet. The President’s highest naval advisers, however, cautioned against the wisdom of naming man a Jewish officer of German descent to the high post regardless of his brilliant record in view of the fact that religious and racial prejudice had unfortunately been made a world-wide issue. Instead, Taussig was named Commander of the Scouting Fleet.

Three years later he was suddenly given the unimportant post of Commander of the Fifth Naval District in Norfolk, Va.—a definite demotion. Whether it was this action that caused him to speak out before the Senate Naval Affairs Committee is something only the Admiral himself knows. No doubt he was chagrined by the relatively unimportant position he was. Given at the twilight of his long career.

Even though it may have been anger that prompted him to testify as he did—and there is no proof that it was—he dared to say what every Navy officer knew to be a fact; what is more, many members of the State Department secretly shared the same views. Had they listened to him, it might not have been necessary to “Remember Pearl Harbor.”

I always like to check my source material, and this is what is publicly available in the Library of Congress: About the Southern Jewish Weekly

The Southern Jewish Weekly began publication in 1939 when editor Isadore Moscovitz, a University of Florida Journalism graduate, merged the Florida Jewish News and the Jewish Citizen to create a new newspaper that would be “an independent weekly serving American citizens of Jewish faith.” The Weekly considered itself the “oldest and most widely circulated Jewish publication in this territory.”

Pensacola was home to the first known Jewish community in Florida in 1763 after the Treaty of Paris was signed. Once England acquired Florida, non-Catholics were allowed to freely settle in the colony. The Jewish community in Florida began to flourish in the late 1850s as they began to establish organizations that would meet their educational, social, and health-related needs. The Jacksonville Hebrew Cemetery was the first Jewish institution to be established in the state in 1857. By 1900, there were six established congregations across the state in Pensacola, Jacksonville, Key West, Ocala, and Tampa. The community continued to grow, and by 1928, approximately 10,000 Jews lived in Florida, with approximately 10% of the community residing in Jacksonville. As of 2020, over 600,000 Jews are living in Florida, making up 3% of the overall state’s population.

The Southern Jewish Weekly was a member of the Religious News Service, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the American Jewish Press Club, and the Independent Jewish Press Service. It was published in Jacksonville once a week, with every issue typically being eight pages. In October 1943, Moscovitz published an announcement noting a change in publication frequency due to World War II. The Weekly became the Southern Jewish Monthly, publishing a single issue every third Friday of the month. During this time Moscovitz served in the war, leaving his wife Ethel Moscovitz to manage the paper and serve as its editor. The paper continued as a monthly until January 1947 when Moscovitz returned to the United States and resumed the paper’s weekly publication schedule.

The Weekly was “opposed to communism, fascism, and Nazism and [was] dedicated to the ideals of American democracy.” It reported on WWII, providing readers a unique perspective from the community most affected by the tragedies of the war. The newspaper often reported the murders and atrocities endured by the Jewish community. It also reported on activities of anti-Semitic hate groups in the United States, like the Ku Klux Klan.

- The destroyer escort Joseph K. Taussig (DE-1030) was named in his honor, while the destroyer Taussig (DD-746) was named in honor of his father.

- Admiral Taussig Blvd. in Norfolk, Virginia, near Naval Station Norfolk, is named in his honor.

On 8 December 1941, President Roosevelt ordered the reprimand removed from Taussig’s personnel file, after his son, Ensign Joseph K. Taussig Jr. was severely wounded and lost his leg, earning a Navy Cross while serving on the Nevada during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Taussig’s request to return to active duty was ultimately granted in 1943 and he served in the office of the Secretary of the Navy on the Naval Clemency and Prison Inspection Board, the Naval Discipline Policy Review Board, and the Procurement and Retirement Board, until 1 June 1947, only a few months before his death.

Vice Admiral Taussig died on 29 October 1947 at Bethesda Naval Hospital. He was one of a very few individuals who served in the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II.

“What might have been…” seems especially poignant considering the world in which we live now. Informative as always Mister Mac!

Agree…

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.