I’ve heard submarines called many things in my life but this was the first time I have ever heard the term “Tigers of the Sea”. It’s been over a hundred years since “THE MARVEL BOOK OF AMERICAN SHIPS”, by Captain Orton P. Jackson, U.S.N., and Major Frank E. Evans, U.S.M.C. was published. The term is one that they included in their writing.

There is no preface in the book that explains the purpose for which it was written. Since it was published in 1917, it is almost assured that most of the material was written before the Americans entered the First World War. The book is broken into types of chapters one would expect from a contemporary book about the US Navy. In over 380 pages, the authors cram in a lot of information about the American Navy past and present. But surprising to me was the placement of the submarine section.

Up until 1914, the giant battleships were considered the most powerful weapon afloat. Indeed, even in 1917 when this book was published, that had not changed. Pearl Harbor and the annihilation of the British Battleships by Japanese airplanes was a faraway series of events. So it was surprising that the authors chose to place submarine warfare in the second chapter rather than at the end as an afterthought. Maybe the sinking of the Lusitania and many other ships by the Huns was fresh on their minds and maybe the authors were just enthusiastic about the new weapons and their potential.

For whatever the reason, the story of the American submarine occupies a very significant place in the book they ended up publishing.

Who manned the “Tigers of the Sea?“

The character of the men who pioneered the use of submarines has always been described in heroic terms. The sea is a dangerous place to begin with. The testimony is how many ships throughout man’s history have been damaged or lost even in times of peace. The sea is unpredictable, ever changing and possesses more power in its bosom than nearly anything else on earth.

The sea can also be relentless when it is in the wrong mood. I have ridden her waves on everything to a submarine that was nearly as old as I was at the time to the largest carrier of its day (USS Nimitz). Both offered little comfort when the waves were on the rise and we were far from land.

But operating a submarine in the early days was particularly challenging. The construction of the boats limited their ability to dive in very deep waters and the modern safety devices that are taken for granted in this age simply did not exist. The men who sailed on the fledgling “subs” were simply audacious in their courage. The authors called the boats “The Tigers of the Seas” and simply stated that the men who operated them required nerves of Iron and steel.

The US Navy was still focused on the power of its battleships for future influence. But it is interesting to see how some were impressed enough to capture the life of these sub sailors and their craft. It’s also interesting to note that some of the same challenges they face then are still challenges today.

From: The marvel book of American ships, by Captain Orton P. Jackson, U.S.N., and Major Frank E. Evans, U.S.M.C. With twelve colored plates and over four hundred illustrations from photographs. (1917)

OUR UNDERSEA FIGHTERS

OF all the craft that make up the Fleet, from the grim dreadnought and its powerful fourteen-inch monsters to the fussy steam-launch and its one-pounder gun in the bow, there is none that should have the same interest for the American boy as the submarine. Of all the units of the Fleet it is the one distinctively American product of inventive genius. It was an American, Robert Fulton, then living in France, in 1800, who designed the first submarine. It was another American citizen, John P. Holland, who built the first submarine that met its tests successfully, and which carried within its steel skin practically all of the principles of the modern submarine.

As far back as the sixteenth century men dreamed of a boat that could travel beneath the seas, just as men dreamed of a craft that could sail through the skies with the freedom of a great bird. Not until the two Americans, Fulton and Holland, made their practical contributions to this end did the submarine of to-day emerge from the realms of visions to its grim power. Jules Verne, in his remarkable romance, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, only sketched the wonderful possibilities of the craft that he dreamed of.

Of all ships, the submarine is the only one that can maneuver beneath the waves as well as on the surface, and the dreadnought of 27,000 tons is an easy victim to the submarine of one-fiftieth her tonnage when the submarine takes her unawares.

It remained for the European War, more than a century after Fulton’s design, to vindicate the prophecies that the submarine would play a great part in the struggle for the control of the seas. The war stripped the submarine of much of its mystery, for every American boy now knows something of the part it plays in naval warfare, of how it fights and how, in turn, it is hunted to be either captured or sunk.

It must be a matter of national pride that Americans gave to that war one of its mightiest engines. American-built submarines, too, showed to the world that the tiny undersea craft, assembled in this country, were heard from in the fighting at the Dardanelles, having, traveled five thousand sea leagues away.

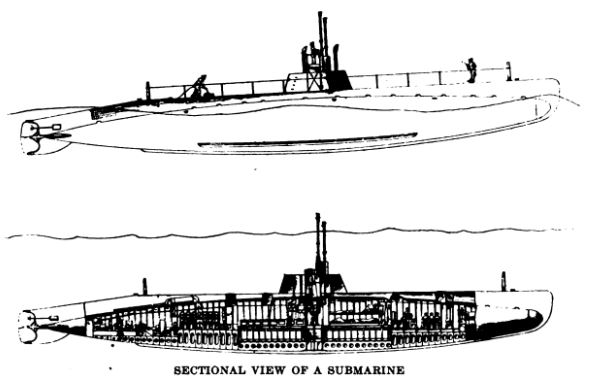

SECTIONAL VIEW OF A SUBMARINE

Ever since the United States Government accepted the first successful submarine, the Holland, in 1898, all navies of the world have built, and are building, fleets of submarines. They have increased in size, power, and seagoing abilities until Germany produced the super- submarine, the Deutschland, with its displacement of 2,300 tons submerged, in the summer of 1916. The Deutschland was the first demonstration of the part that the big undersea craft are destined to play in the development of commerce as well as its destruction. Unarmed, she ran the formidable British blockade from Bremen to Baltimore and back, her hull loaded with priceless contraband, and returned, making Bridgeport, Connecticut, on the second trip.

The ordinary type of submarine used by the United States Navy has about 500 tons of submerged displacement, much smaller than the seagoing submarines used by the European nations in their raids on commerce and in their blockades. It was left to them to prove that the submarine was even a more formidable weapon, in some respects, than those who knew it best under peace conditions had claimed. There had been practically no chance to test out its efficiency except under peace conditions. Naval officers not only had had no practical opportunity to prove out their theories of attack, but there had been no practical chance to build up a defense against the untried weapon.

Like the torpedo, without the use of which the undersea boat would have remained little better than a toy, the submarine is so shaped. In reality it is a submerging or diving torpedo-boat, driven on the surface by oil engines, below the sea by electric power, and discharges torpedoes at its enemy.

The torpedo tubes of a submarine vary in number according to the size of the boat. Some types carry their tubes aft, some on the broadside, but the majority carry them forward. The torpedoes used are the same as those fired from destroyers and from battleships.

The torpedo itself is astonishingly accurate because of the gyroscopic mechanism which, acting on a vertical rudder, holds it true to its course. The difficulty in aiming the torpedo in submarine work is great and this alone has saved many ships from destruction.

Because the submarine does the greater part of its deadly work while partially or totally submerged, and because its only protection against an enemy ship lies in diving, it is built to meet the great pressure on its hull. Unlike other craft it is therefore usually built in circular sections, because this form gives it the strength needed.

When the submarine runs on the surface it is driven by oil engines with a speed which ranges around 15 knots. When the “sub,” as its crew calls it, dives and runs submerged, it is propelled by electric motors which are fed by storage batteries. At target practice they run submerged at about 8 knots, and one improvement for which all navies are striving is to increase this speed below water.

The new submarines that are now building for our Navy will average about 800 tons displacement when submerged, be about 250 feet long and will have a speed on the surface of about 19 knots, and a maximum speed below of nearly 14 knots. The “subs” of this type will cost $1,200,000 without figuring on the armor and the armament. To build them longer would increase the danger in diving, but they will be as seaworthy, speedy, powerful, and comfortable as any submarine afloat.

At one stage of the submarine’s development carbonic acid gas was a danger to which running awash the crew was exposed and it was customary to carry white mice as pets on the “subs,” for they quickly collapsed at the first trace of it. Now mechanical devices show the formation of any gas, such as hydrogen, which is odorless. As the current developed while running submerged is quickly used up at high speed, the undersea fighter usually runs at slow speed, using the high speed only for short spurts. The current can only be replaced by coming to the surface, operating the oil engines, and recharging the batteries; so that the maximum speed can only be made while on the surface.

Like the torpedoes that have made the submarine the most dreaded of all sea fighters, the modern submarine is divided into watertight compartments. These are the torpedo, crew, battery, diving, and engine compartments; spare torpedoes are carried in the crew quarters.

Life on a submarine is no bed of roses, but the Navy never lacks for volunteers for the flotilla. It carries extra pay to make up in part for its discomforts, but more than all the lure of danger attracts the American bluejacket.

The living quarters, built for crews ranging from ten to thirty men, are damp, cramped, and the air is usually foul with oily vapors and stale air. At best the amount of fresh air in a submarine is one- third that which a man enjoys on a surface-operating ship. In rough weather, whether running above or below water, the percentage of seasickness is high even with men who never have felt its pangs on board a battleship in the worst of storms. On the surface, in nasty weather, everything is closed but the conning tower hatch and then conditions within the “sub” are almost as bad as when running submerged.

In the regular channels it is hard to sink to a depth that will bring any relief, but out in the open sea, when a gale rages, she can sink to a depth of one hundred feet. Even then there is an up and down motion, which the crew calls “pumping,” that cannot be escaped. It is only on cruises of a fortnight or so, however, that a submarine crew gets no relief from these conditions. Between runs, and while in port or at the submarine base, the crews live in airy barracks or sling their hammocks in tenders that are detailed with each flotilla as a mother ship.

Little shows above the deck of the submarine on the surface but the conning tower, which stands about six feet above deck. The surface navigation is done exactly as with other vessels, the captain and helmsman using the conning tower for their station. Below the water the periscope takes the place of the conning tower. A rapid-fire gun, running in caliber up to one that fires a fourteen-pound shell, and the radio for signaling purposes, are housed in the superstructure or recessed in the hull when the submarine makes its dive. The gun is used both for halting merchantmen that try to escape and in blockade duties. A submarine bell for use while submerged has been added to the modern submarine’s signal equipment; and another great improvement ite the use of electric stoves for cooking, the current being taken from the storage batteries.

When the submarine finds it necessary to submerge preparatory to an attack, to escape an enemy ship, or for practice, all openings in the hull are closed by watertight hatches. The Holland type has diving rudders, and the Lake boat—our two leading types—flat projecting fins forward and aft, called hydroplanes, and both sink nearly on an even keel. Water is then admitted to destroy the natural buoyancy of the craft, by way of the ballast tanks. The diving rudders, forward at the bow, and aft at the stern, are deflected, and the water closes over the sea tiger, leaving but a few bubbles to mark its going.

A gauge registers the depth to which she sinks. The greatest depth at which she operates is ordinarily one hundred feet, but submarines have operated as far down as from two hundred to two hundred and fifty feet. Here the pressure of the water is so powerful that there is danger of crushing the sides and being unable to rise to safety. To test the strength of a new submarine’s hull they must submerge to one hundred and fifty feet, if they are of the large type, as this has been found to leave the right margin of safety.

When running submerged the swish of a ship’s propellers in the vicinity can be heard inside the submarine; and when the captain is thus warned of the enemy’s presence he can rest in peace on a clean bed of sand while the submarine hunters cruise vainly above.

Without the periscope the submarine would be a blinded fighter. It’s most deadly work is done at a submerged distance which shows but a foot or two of the periscope’s tip. The periscope is a long vertical tube of small diameter, with prisms at either end and the necessary lenses. Eighteen feet above the deck it runs; and below, where the other end pierces the hull, is the eyepiece for the observer.

It can be turned in any direction, and when an enemy ship, or a merchantman trying to run the blockade, comes within its field, the submarine is suddenly transformed into a formidable and stealthy sea tiger. The periscope becomes its eyes, and the dials, compasses, and other instruments of the fire-control its brain. The engines that carry it to effective range are its swift, tireless legs, and the destructive charge of 250 pounds of gun-cotton in the unleashed torpedo the death- dealing jaws and rending claws of the great cat that has seen its prey and steals up on it with the skill of a tiger stalking a buffalo.

The submarine chooses to fight at as close quarters as can be had with safety, to cut down the chance of missing its big quarry, and because an unlimited supply of the $8,000 torpedoes cannot be carried. As soon as its target is discovered—it may be miles distant—the captain takes his bearings and down goes the “sub” and with it the telltale periscope that, once seen, draws a shower of shells which would crush its skin as though it were but an eggshell. Then he dives and steers by his bearings to a range as close as is wise. Up goes the periscope for a final aim, just high enough to make it certain, and the submarine swings about to bring its torpedo tubes in line with the target. In the time that the torpedo covers a thousand yards a dreadnought will steam twice her length; and this, and the conditions of the weather, must be quickly and accurately considered by the “sub’s” skipper. The war has shown that when a submarine is discovered the only safety for a vessel is to steer a zigzag course and crowd on enough steam to let the torpedo go tearing by. The slightest error in aim is fatal to a submarine’s chances of a telling hit.

When the exact position is determined comes the word: “Stand by to fire a torpedo! . . . Fire!” Straight as an arrow speeds the cigar-shaped missile and its deadly gun-cotton, traveling ten to fifteen feet below water to make its hit beneath the vulnerable waterline of its target. The compressed air that is its motive power shows in the torpedo’s wake in a sinister track of light air-bubbles. The impact of the torpedo’s head on the hull of the luckless ship explodes the shattering charge of gun-cotton and this first explosion is felt slightly within the hull of the waiting submarine. Often there is a second explosion if the torpedo finds the ship’s boilers or her powder magazines.

Then the diving rudders are reversed, the ballast tanks pumped out by compressed air, and the long, shark-like body creeps warily to the surface for a “look see,” as the sailors have it. The critical moment, whenever a “sub” rises, begins when the periscope has climbed to a point where it reaches the depth of a ship’s keel. It ends only after the periscope’s tip shakes off the water and the captain can sweep the surface with its aid.

All this time his craft is like a great, blinded fish, helpless against attack. As the tip clears the surface the dark shade of the sea fades to the grass green of the undersurface, and then white air-bubbles can be seen as the silver touch of daylight signals the return to the surface. With the nerves of the crew at high tension, iron men though they are, comes the search for the enemy. A seething white cloud of steam pouring from the open hatches and ports of the crippled vessel tells its tale. A few minutes later there is nothing but a huddle of wreckage to show where the submarine has added another to its grewsome toll.

Just as the European War brought the possibilities of the submarine to a skill never dreamed of, so has it brought to the front the methods of hunting down and destroying or capturing it. On blockade duty trawlers, towing between them grappling lines, sweep suspected areas for them. To protect the clumsy trawlers torpedo craft patrol outside with unceasing vigil and tow explosive-laden sweeps behind them. At other points where submarines have been reported are stretched stationary nets with mines above. The explosive sweeps and the mines, when detonated by the touch of the submarine, explode with deadly effect.

Many submarines in the course of the war were caught in nets of wire. Their propellers fouled in the meshes, and as the submarines were closed tight against the water, it was impossible for them to cut the net away. When trapped in this manner their fate was sealed. The initial air carried inside a submarine lasts but little more than half a day. Then air had to be used from the air flasks or “banks” and the foul air could not be pumped out, as then would come a vacuum in which the crew could not live. Three days or possibly four and the trapped sea tiger held only a dead crew.

Seaplanes, when the sea is calm, the bottom light in color, and the air conditions good, can spot and follow submarines when they are within fifty feet of the surface.

It calls for men of iron nerves and quick decision to man our submarines either in peace or in war. Submarine experts look upon the factor of nerves as the most important of all, and they have given to it the title of calculation. Within the cramped walls that are the home of the crew are housed the most intricate mechanisms that man has invented for warfare. Outside its steel walls are mines, great nets of wire, explosives, shells, and seaplanes, all devised for its destruction, and the sharp keels of ships that slice through a submarine as a knife cuts cheese. The smallest shell can penetrate the steel skin, and nets can hold the submarine as helpless as a child in the grasp of a giant.

Danger lies everywhere for the tiger of the seas. The ocean in which it lives is a powder tank that needs but a spark. Only nerves of iron can cope against such an array of enemies. The slightest hesitation of its captain in the face of any one of them means the end of his ship and his crew. As one expert has put it, the whole A B C of submarine warfare is the ability to meet any situation at an instant’s warning and then to act with nerves of steel.