Chapter Twenty: “Like a ballroom brawl with the lights turned out.”

Four days.

From the moment Cassin Young reported on board until the night of October 13th there were only four days for him to prepare for the battle that was waiting just beyond the horizon. The San Francisco had nearly 1000 crew members on board along with Admiral Callaghan and his staff. Most of the crew had been fighting together for a long time. Most recently, under Admiral Scott, they had distinguished themselves and the Navy by their remarkable victory at Cape Esperance.

Prior to that epic battle, Scott had surreptitiously drilled them in combat techniques while overtly performing escort duties at the request of the previous theater commander. This experience paid off when his small force of ships performed a classical “crossing the T” maneuver and defeated the opposing Japanese force. But Admiral Scott and the commanding officer present on that October night had been transferred to their new assignments.

In May of 1941, during the early stages of World War II, President Roosevelt released Dan Callaghan from the position as his personal Naval aid so that he could take command of the cruiser USS San Francisco. Roosevelt wrote:

“It is with great regret that I am letting Captain Callaghan leave as my Naval Aide. He has given every satisfaction and has performed duties of many varieties with tact and real efficiency. He has shown a real understanding of the many problems of the service within itself and in relationship to the rest of Government.”

In April of 1942, Callaghan was promoted to the rank of rear admiral and was appointed as chief of staff to the Commander, South Pacific Area and South Pacific Force Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley. He served in that billet until Vice Admiral Ghormley was relieved on 18 October 1942. Ghormley had been in charge when the disastrous Battle of Savo Island occurred and was struggling with the entire Guadalcanal campaign. Nimitz replaced him with Bull Halsey.

Halsey was the best choice for the moment since he had a reputation for being purposeful and direct.

The men on the ships that were included in his task force were elated overall that a man of action was now going to be in overall charge. Even with the limited resources available, Halsey proved quickly that he was not afraid to take great risks to achieve great outcomes. That included making the maximum possible commitment to relive the beleaguered Marines on Guadalcanal.

The men on Guadalcanal were subjected to constant attacks from the land, sea, and air. The Japanese high command recognized that if they were unable to regain control of the island and expel the Americans, the entire progress they had achieved so far would be threatened. Yamamoto continued to commit his forces to resupply the Japanese troops that were fighting on that tiny island. The airfield stood at the crossroads of the supply chain from America to Australia. If it fell, long range Japanese bombers could attack shipping at will and threaten Australia and the allies that were using her as a staging ground for the comeback. No price was too high on either side and that new spirit of determination would push both combatants to a pivotal moment.

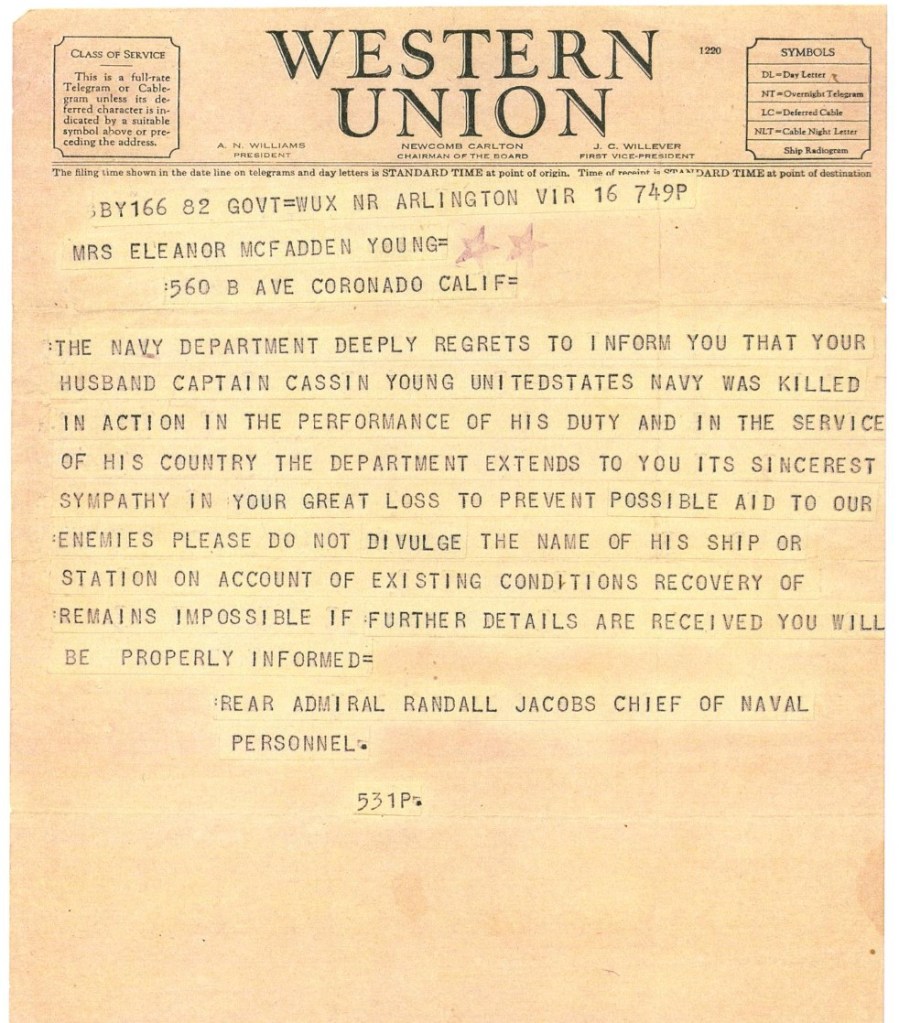

In late October, Callaghan was anxious to get back to sea and embraced the chance to return to the cruiser USS San Francisco as its newest Task Force Commander. Halsey knew that Callaghan had previously commanded the San Francisco so placing him in overall charge of the task force made perfect sense. Callaghan knew Cassin Young from his time at Pearl Harbor and when he selected Young to be the Commanding officer of the CA 38, he sealed both of their fates.

Guadalcanal was not an ideal place for the Marines to fight but neither was it an ideal place for the crews of the ships that would come to their defense.

The tropical heat and constant need to keep the boilers ready for full power made operating the ships a challenge. Below decks, the engine room crews would have continued their struggle against the twin enemies of every ship in war. The first enemy is the environment. Operating a steam powered ship would require continuing effort from the black gangs. A ship that could not easily maneuver in any conditions was a target. And no one on board the San Francisco would ever desire to be a target. The second enemy is fatigue. Even in the best of times, an engine room can wear a person down. But the San Francisco was not operating under a normal tempo. They had been in theater for some time now and the enemy liked to fight at night. The brave men who never saw the shells or torpedoes that would come their way just labored on. They had to have trust in the officers and crew topside that would do all they could to protect the ship during an attack.

Between the decks, men of every rate went about their duties as well. A fighting ship must provide food and every need required in battle or in peace. While the spaces were not as hot as the engine rooms, limited ventilation in many cases made even the most mundane tasks a challenges. But each would perform their duties and prepare for the next battle.

The loss of the battleships at Pearl Harbor was witnessed by many of the Frisco’s crew.

She had been waiting to be dry docked and was stripped of all of her ammunition during the attack. Small arms fire was the best the crew could muster while the fleet was pounded in the nearby waters of the harbor. Being here in the combat zone must have been a grand way of taking the war back to the Japanese that had attacked in such a cowardly way. But even these men must have felt some fear and anxiety. They would play their roles while the battle raged around them. But they would not be able to escape form the fires and explosions that would surely come.

Above decks and in the control rooms, last minute preparations were being completed. The knowledge that some enemy force was coming towards them in the next few days did not escape anyone. What they did not know during those four days was what size and composition that force would take. They had no idea that the Japanese Admiralty were sending battleships and cruisers to try and bombard the airfields into submission.

The reality was this, however. The San Francisco had been built as a treaty cruiser.

Her specifications were mandated by that long ago commitment to a noble ideal of limiting war by limiting the size and scope of warships. She was a capable ship but her main armament of eight inch guns limited her to the type of vessel she would normally approach. Every surface combat ship would have a purpose in the eyes of the planners. Battleships fought battleships. Cruisers fought Cruisers. Destroyers would provide a variety of services including torpedo attacks. But in all of the war games, equal ships were designed and used against equal ships.

The night of the attack, San Francisco represented the largest caliber guns that the small group of 13 American warships assembled for the task could muster.

The IJN battleships Hiei and Kirishima were busily steaming towards the area that would provide the space for this night battle. With her destroyers and lone cruiser, they presented a significant advantage in firepower over the Task Force the American’s were sending. Huge fourteen-inch guns on both battleships had a longer range and potentially could rip the thin-skinned cruisers on the American side to shreds. In an open sea battle, there would not have been as much of a fight. The fast battleships could lay just out of range of the cruisers and fire with impunity.

But the battle that was about to begin was not an open sea battle.

It would also not be the battle the Japanese wanted. Both of the battleships were preloaded with bombardment ammunition rather than anti-ship shells. Armor piercing shells were designed to penetrate and destroy surface ships from great ranges. But the Japanese Admiral was not prepared for the Task Force. One can only imagine that he did not believe that a groups of cruisers would dare take on his superior ships. Especially not at night. The Americans had a mixed record of night fighting and had not yet perfected their use of radar in overcoming that weakness.

The two fleets sailed towards each other with specific missions. The Japanese were to take station off the island of Guadalcanal and expend as much ammunition as they could to bombard and destroy the American airfield and support structures. The following days would bring a reinforced number of troops that would join the existing Japanese army units locked in a desperate struggle, this action would turn the tide at Guadalcanal once and for all. The island would be retaken, the new airfield would be populate with Japanese aircraft and the flow of supplies to Australia and New Zealand would be stopped once and for all. The victory would prove to the Americans that Japan was superior in its tactics and forced a quick end to American plans to recover all of the territories Japan had taken.

The mission Halsey had given to Admiral Callaghan was simple. Stop the Japanese fleet in its tracks and defend the Marines and Army units now on Guadalcanal. The battleships and remaining carriers would come soon but for this night, October 13th, the Americans had to fight with whatever forces they had at hand.

On the 10th of October, San Francisco, which was now the flagship for TG 67.4, got underway again toward Guadalcanal. She was soon spotted by a Japanese twin float reconnaissance plane which reported her position and passage back to headquarters. On the morning of the 12th, the Task group arrived off Tunga Point, and the supply ships began offloading their precious cargo of food and supplies.

The afternoon brought the first aerial attack.

In the middle of a sweltering afternoon, a flight of Japanese aircraft was spotted approaching and the ships at anchor got underway to perform protective and evasive maneuvers. At approximately 1408, 21 enemy airplanes attacked the force. The sky was filled with anti-aircraft fire from all of the ships. At 1416, an already damaged torpedo plane dropped its torpedo off San Francisco’s starboard quarter. The torpedo passed alongside missing the ship, but the plane crashed into San Francisco’s control aft, swung around that structure, and plunged over the port side into the sea. Fifteen men were killed, 29 wounded, and one missing. Control aft was demolished.

The ship’s secondary command post, Battle Two, was burned out but was reestablished by dark. The after antiaircraft director and radar were put out of commission. Three 20-millimeter mounts were also destroyed.

The San Francisco was damaged but still in fighting trim. There was no turning back now as night fell on the island and surrounding waters.

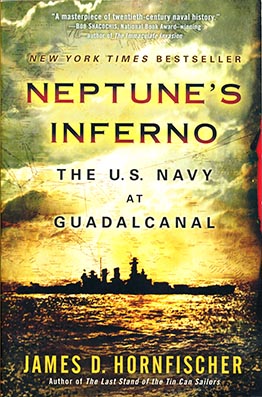

The night action that followed has been written about many times since the end of the war. The most comprehensive volume written to date is probably Neptune’s Inferno by James Hornfischer.

The Task Force under Admiral Dan Callaghan steamed into history that night in one of the most chaotic surface actions of the war. The USS San Francisco was at the center of the American force and was the place where destiny would finally catch up with Captain Cassin Young.

The battle between the two forces started shortly after midnight on November 13th

A superior Japanese task force was sailing to bombard the Marines and try and gain a victory for the Japanese Army and Navy. The only thing that stood between them and victory that night was a collection of American cruisers and destroyers. Most did not have effective radars. In fact, the one cruiser that was equipped with the latest equipment was not in the right position at the right time. Even if it were, the man in charge was not as familiar with how to take advantage of the technology. Admiral Callaghan had recently returned to the fleet and had not trained on this new way of fighting.

Cassin Young was the Commanding Officer of the San Francisco but on this night, he had only been Captain for a short time. Callaghan had chosen the San Francisco as his flag ship and Callaghan was actually experienced at the helm of the mighty ship. The Medal of Honor awardee that had escaped death so many times before would not escape this night.

The chaos of a battle plan gone completely off course had to have been dizzying. Darkness pierced by spotlights, shells, explosions and fires was all part of the unforgiving night. The San Francisco fought with all of her might against a ship that was superior in size and strength but in the end, she was just outgunned.

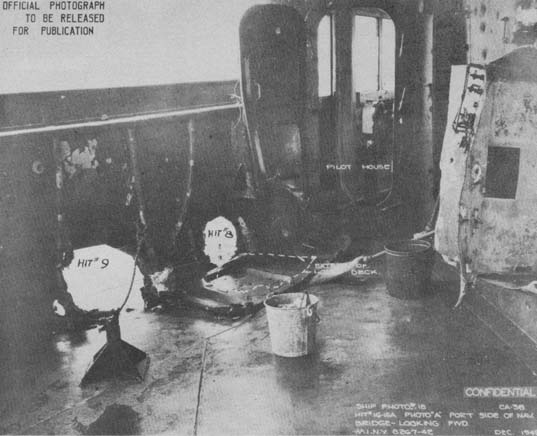

At 0202 in the morning, shells from the Japanese Battleship Hiei’s second salvo struck the bridge of the San Francisco.

The deafening explosion immediately killed Admiral Callaghan and three of his staff officers.

Cassin Young was mortally wounded. He would not last the day.

He had spent his entire lifetime preparing for the battle that finally came. But his story ended there in a haze of smoke and the burning sights and sounds of a brave ship that had been his last assignment.

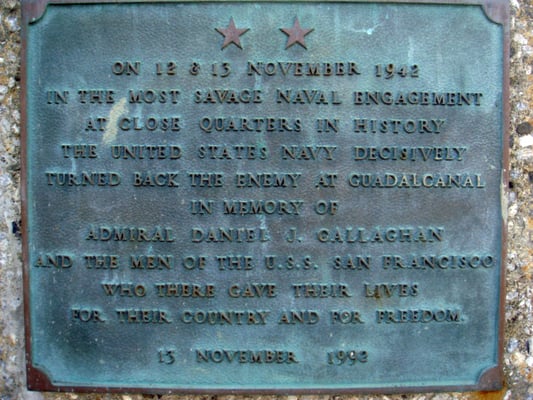

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was the last major attempt by the Japanese to seize control of the seas around Guadalcanal or to retake the island. In contrast, the U.S. Navy was from that time on able to resupply the U.S. forces at Guadalcanal at will, including the delivery of two fresh divisions by late December 1942. The inability to neutralize Henderson Field doomed the Japanese effort to successfully combat the Allied conquest of Guadalcanal. The last Japanese resistance in the Guadalcanal campaign ended on 9 February 1943, with the successful evacuation of most of the surviving Japanese troops from the island by the Japanese Navy in Operation Ke. Building on their success at Guadalcanal and elsewhere, the Allies continued their campaign against Japan, which culminated in Japan’s defeat and the end of World War II. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, upon learning of the results of the battle, commented, “It would seem that the turning point in this war has at last been reached.”

Historian Eric Hammel summarized the significance of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal with these words:

“On November 12, 1942, the (Japanese) Imperial Navy had the better ships and the better tactics. After November 15, 1942, its leaders lost heart and it lacked the strategic depth to face the burgeoning U.S. Navy and its vastly improving weapons and tactics. The Japanese never got better while, after November 1942, the U.S. Navy never stopped getting better.”

General Alexander Vandegrift, the commander of the troops on Guadalcanal, paid tribute to the sailors who fought the battle:

“We believe the enemy has undoubtedly suffered a crushing defeat. We thank Admiral Kinkaid for his intervention yesterday. We thank Lee for his sturdy effort last night. Our own aircraft has been grand in its relentless hammering of the foe. All those efforts are appreciated but our greatest homage goes to Callaghan, Scott and their men who with magnificent courage against seemingly hopeless odds drove back the first hostile attack and paved the way for the success to follow. To them the men of Cactus lift their battered helmets in deepest admiration.”