Chapter Nineteen

Into the battle. Every man a hero

The Marines that landed on Guadalcanal were about to write a page into history that would be written with blood.

This tiny island in the Pacific should not have been the place where the allies would start their long drive to Tokyo. But observation planes had sighted a Japanese construction battalion cutting an airstrip into the fields and Army and Navy planners could read a map. The establishment of an airfield in this small remote island would have a profound influence on the war’s outcome. The Japanese envelope of influence had already stretched well past all of the artificial boundaries put in place by the American and other forces before the war. By the summer of 1942, every major outpost including the Philippines and Malaysia had fallen to the conquering Nipponese Army. The dream of a Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity sphere was quickly becoming a reality and only Australia and New Zealand remained free from the Japanese Empire’s influence.

Guadalcanal is a small island in the Solomon Islands.

It was a tropical jungle infested place where some local natives and a few foreigners had plantations. When the Japanese took the island, it was not in the grand scheme of things for it to be a major player in the war’s efforts. The airfield however would pose a grave danger to shipping that needed to cross nearby on its way to supply the bases that would be the launching point for MacArthur’s return to the Philippines. Truthfully, those same military supplies and troop convoys were vital in repulsing the Japanese attacks on Australia and New Zealand. With an airfield, the Japanese pilots could sink the needed ships before they made it halfway to their destination.

A makeshift operation was assembled using borrowed troops and ships.

The invasion was difficult, but the establishment of the base and a new American airfield would prove to be a challenge beyond anyone’s imagination. The fleet was still in the process of being rebuilt after the debacle at Pearl Harbor and the war in the Atlantic was deemed a higher priority for nearly every resource that might be available. There were only two battleships in the Pacific at the time and only a handful of aircraft carriers. The invasion and support would have to come from a collection of precious cruisers and destroyers that had to face a superior force of Japanese surface ships. Some of the cruisers that would come into play were new since the Navy had ramped up production just prior to the start of the war. But many were older and slower big gun cruisers that would be needed to counter the larger and more powerful Japanese ships.

The rear area for the naval forces was in Noumea. The Vestal would be needed to repair the many surviving ships that were trying their best to support and resupply the Marines.

On April 18, 1942, the commander of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester Nimitz, arrived aboard the still-damaged Vestal. During this visit, he would award the newly promoted Captain Young with the Medal of Honor for his valorous actions on December 7. The Vestal would also be awarded a battle star for her courageous action under fire that fateful day. This reward was not common for service ships and was significant in its recognition of what the aged ship had already accomplished.

In August 1942, the USS Vestal was sent to support the fleet that was learning by experience the lethality of the Japanese surface fleet near Guadalcanal. New terms would be entered into the halls of naval history: Savo Island, Cape Esperance, Iron Bottom Sound. These and many more were the names for the naval battles that would rage between the Allied and Japanese fleets. Many of the ships sent out never returned. But each desperate battle was critical to establishing a secure base for the Marines and later Army forces.

From the beginning, more and more Japanese forces were committed to the battle.

Between the nightly bombardments and resupply missions, the Japanese command found itself being drawn deeper and deeper into a conflict that it had not really planned for. The same can be said about the American forces. The beleaguered Marines had originally been left with limited supplies as the US Navy tried to protect its scarce combat and supply ships. As the Japanese ramped up their attacks, the Americans had no choice but to commit as much of the Pacific fleet as they could to counter the foe.

On the Island, night after night, the Japanese ships freely ranged and bombarded the hapless Marines with naval gunfire. The conditions on Guadalcanal were already miserable with the weather, the mud and disease. The constant attacks of the Japanese forces both day and night took its toll on the defenders. Their only relief was the ability of the Cactus Air Force to counter the attacks when they were able to fly. The Japanese knew this as well and decided that a major bombardment would be needed to supplant the ones that were more sporadic.

In late October, the Vestal was moved even closer to the action by being stationed in Noumea.

Admiral William “Bull” Halsey had relived Admiral Ghormley and promised that he would shake things up in the theater of action. Halsey knew that he had to support the Marines with everything he had, and that meant that a lot more of his limited number of ships would be sent into the areas around Guadalcanal. He recognized that this action would probably result in damage to the few warships he had and he did not want to have to send them all the way back to Pearl Harbor for repairs. His ships would have to be repaired in theater as quickly as possible and return to the fight. The USS Vestal arrived in Noumea on October 31 and began work the same day.

On the same day, Admiral Dan Callaghan took command of the cruiser USS San Francisco in Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides Islands and requested that Cassin Young join him on board as the new Commanding Officer. Captain Young departed as Commanding officer of the Vestal on November 7th and reported on board the San Francisco on November 9th. It was just three days before the Naval Battle for Guadalcanal would be fought.

There would have been little time for fanfare or ceremonies that typically accompany a change of command. In peacetime, the arrival of a new commanding officer is celebrated with celebrations for both the new commanding officer and the person he is relieving. But October 1942 was proving to be one of the most pivotal months of the long Guadalcanal campaign both ashore and afloat. Many ships were already streaming back towards Noumea needing repairs that would allow them to continue the fight. This sense of urgency would continue on board Vestal for the rest of the war.

Cassin Young would not have much time to become acquainted with the ship that he now commanded.

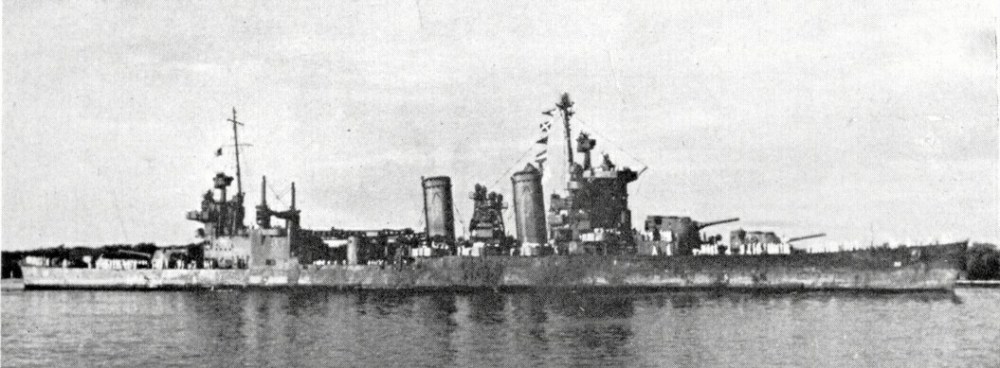

The San Francisco was a heavy cruiser sporting eight-inch guns and an array of secondary weapons that would make her a formidable foe. Built in the early 1930’s and commissioned in 1934, she was a typical Treaty Ship. Weighing in at ten thousand plus tons she was well equipped to operate independently or in groups of ships. Like all of the ships built during her era, armor was sacrificed in order to meet the treaty rules and still have a ship that could go face to face with another major ship in battle.

Admiral Callaghan had been the Commanding Officer of the San Francisco before the war and was called a Fighting Admiral. He had prepared for these days for most of his career. Immensely popular and strikingly handsome, he had been a Naval Aid to President Roosevelt. Roosevelt reluctantly let him return to the battlefield and was stated to have felt his loss both deeply and personally.

“It is with great regret that I am letting Captain Callaghan leave as my Naval Aide. He has given every satisfaction and has performed duties of many varieties with tact and real efficiency. He has shown a real understanding of the many problems of the service within itself and in relationship to the rest of the Government.”

Thus wrote Franklin Delano Roosevelt, with his own hand, in a final fitness report for Dan Callaghan, on March 1, 1941.”

(Fighting admiral; the story of Dan Callaghan. Murphy, Francis X. (Francis Xavier), Page 152)

The Admiral’s reputation had been solidified in the outstanding performance he exhibited in the early days of the war in the Pacific. One of his your officers wrote this to his father after an engagement with the enemy:

“Late that night, a young lieutenant, Jacques R. Eisher, sat down to write to his father. This is what he had to say: One of the finest things I have ever seen is the way our Captain acts on the bridge. As I have perhaps mentioned before, he is D. J. Callaghan, who was the president’s Aide before Captain Beardall. I have stood many, many bridge watches with him out here, and it is a comfort to know the ship is in his hands. One can feel no more secure with 20 inches of armor. He knows his job and his grave responsibility to his men and his country. He reaches important decisions coolly, correctly and fearlessly. I have no doubt but he will be made an Admiral in the near future, and his leaving the ship will be a great loss. It is seldom you can get together 1,000 men, every one of whom in his position is critical to a fault, who can say nothing but the best for their skipper. I have heard nothing but praise from the seamen 2nd class and up.”

(Fighting admiral; the story of Dan Callaghan. Murphy, Francis X. (Francis Xavier), 1914-2002.)

In Father Murphy’s book about Admiral Callaghan, he notes that Cassin Young was a personal friend and that Callaghan had personally requested Young as the San Francisco’s Commanding Officer.

Even though the ship was surely about to be tested to its limits, the Admiral saw the qualities he admired most in Captain Young and must have felt that despite having no previous cruiser experience, he had tackled every other challenge leading up to this day and would surely master this new assignment. It is possible to believe that a Fighting Admiral would see the true courage of a man who had been blown from the deck of his previous ship in the heat of the worst catastrophe in US Naval history to date and managed to pull himself back on board. This would be the man anyone would want beside them in a fight.

The day before the night battle was one which included leaders who had a number of connections. Rear Admiral Scott, who would sail on the Atlanta was a classmate of Rear Admiral Callaghan in the Naval Academy class of 1911. Captain Cassin Young and Captain Lyman Knute Swenson on the Juneau were Naval Academy classmates from the Class of 1916. None of the four men would survive the engagement to come.

The defining moment was just days away for both men and their faithful crew.

Mister Mac

Next up – Chapter Twenty: Like a ballroom brawl with the lights turned out

Mister Mac – I am looking for “Next Up – Chapter Sixteen: “When the World is at Peace, a gentleman keeps his Sword by his side.” – Wu Tsu” I have accessed chapter 15, but the next chapter jumps to chapter 17. Was chapter 16 ever posted?

Thanks for any update you can provide.

Dave Violette Cell: 704-651-6320

Good catch. It was still in draft form but is published now