Chapter Fifteen: If you are in a boat, you are more afraid of fire than you are of water. (Japanese Proverb)

The Japanese radio station at Iwaki signaled to the Radio Corporation of America’s local station that Yokohama was on fire.

The massive earthquake that struck the empire of Japan on September first demonstrated the power of nature in overcoming the meager achievements of mankind. Just seventeen miles southwest of Tokyo, this city had a population of half a million people. The city was famous for being the center of the silk industry and had the distinction of being the host to the visit of the American Navy under Commodore Perry. This visit set in motion the modernization and industrialization of the island nation in a time where the old ways were grudgingly giving way to the new ones.

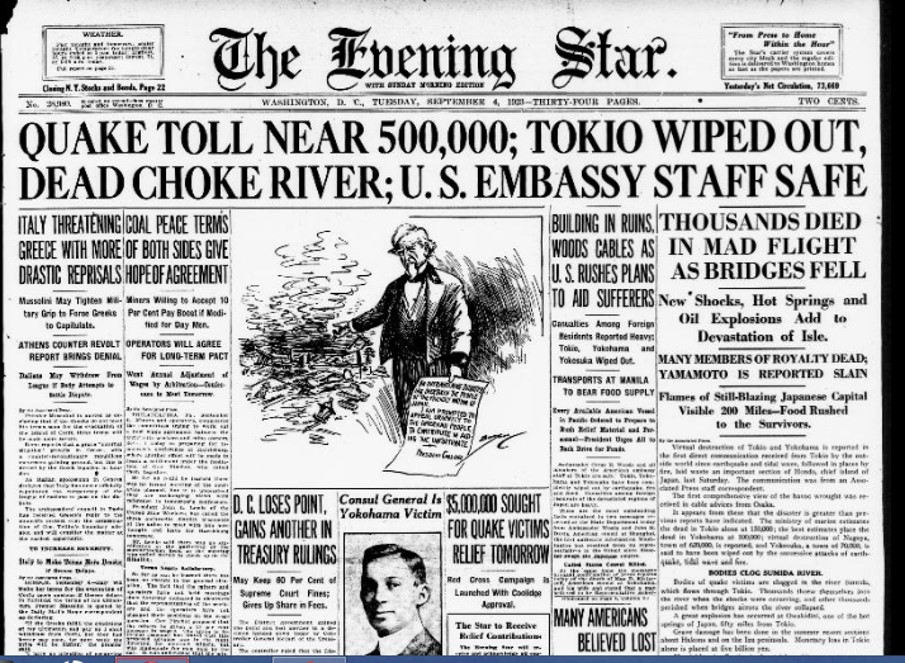

Over the next sixteen days, every major city in the wake of the deadly earthquake would experience fires, building collapses, failure of all of the transportation infrastructure and even the loss of many of its citizens. The Washington DC papers would keep the stories on the front page for an almost unheard of two weeks before they finally were replaced by other tragedies and stories closer to home. Americans would be fearful as they came to understand the magnitude of the event and the close proximity of so many Americans in so many walks of life. Missionaries, government representatives and members of the Navy Department made up part of the large numbers of Americans who were present in Tokyo and the surrounding areas when the quake hit.

When a quake strikes, the frail nature of society is often demonstrated when the means for communication fail. This was certainly true in the Kanto Quake.

The Navy Communications Department had already shown some success in transmitting and receiving messages over great distances, but these demonstrations happened under the most ideal circumstances. The American Asiatic fleet was not in Japanese waters at the time of the incident but they were quickly identified as a possible source for providing what would become a massive need for food and medical supplies. The eighteen destroyers on patrol on the far eastern waters would take at a minimum two and a half days to reach Yokohama. That is not counting the amount of time needed to locate and embark the needed supplies before sailing.

Yokohama was a key area for the Americans since so many had chosen that area to live in while working and living in Japan. There was an American Naval hospital located there with a limited amount of medical staff. But the early thoughts were that if they had survived intact, it would be a natural place to muster aid and assistance. Admiral Anderson was in charge of the Asiatic fleet and it was expected that he would send the available ships to the Yokohama location to begin recovery efforts.

Day over day, newspapers increased the amounts of the dead from hundreds to thousands to greater numbers.

The quake not only caused fires and building collapses, but tidal waves also followed sweeping many of the hapless victims out to sea. Even the royal family was touched by the powers as young members in Kamakura were grabbed by the sea and drowned. Tokyo was devastated as flames swept the city and firefighting water systems were destroyed. The flames could be seen as many as seven miles away from the city as every part of the infrastructure was leveled to the ground. The density of the buildings and the light wooden and bamboo construction of most of the dwellings had subjected Tokyo to disastrous fires in the past. None of those fires had the magnitude of this one because of the inability to combat the blazes once the city’s water networks were disrupted. Each time the fires had come before, the opportunity to rebuild and enlarge the streets had led to improvements. But the trends to continue to use available and cost effective materials such as wood and bamboo was a hard path to change. Even as the embers would start to cool, the need to provide affordable housing would have a powerful impact on the families and communities that would make decisions that someday would visit them again.

The American Navy (among many of the world’s seagoing powers) did arrive at last filled with many items that were meant to help the Japanese recover from this tragedy.

President Coolidge addressed Emperor Yoshihito with a message of sympathy on behalf of himself and the American People. “At the moment when the news of the great disaster which has befallen the people of Japan is being received,” the President’s message said, “I am moved to offer you in my own name and that of the American people the most heartfelt sympathy and to express to your majesty my sincere desire to be of any possible assistance in alleviating the terrible suffering to your people.”

The first American ships arrived on Thursday September the sixth, five days after the initial earthquake. By that time, the homeless numbers exceeded one million people and the fear that colder weather was approaching spurred on many of the relief efforts. In the United States, large fund drives were being organized and over Five Million Dollars had been collected for relief in just a few days. Casualty lists of Americans finally started to come in and while there was a large loss of life, many more survived than had been originally thought. The hospital at Yokohama had been destroyed and some of the Navy personnel were lost but not all. By September twelfth, the casualty estimates that included dead, injured and missing amounted to nearly one million, three hundred and fifty seven thousand. A total of three hundred and fifteen thousand dwellings were destroyed. The American Ambassador had barely escaped with his life as the ceiling above him crashed down and his wife escaped to the nearby Dutch legation through a shower of burning sparks caused by a shift in the wind.

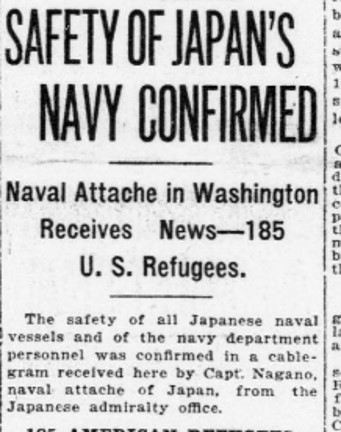

On the same day the casualty reports were issued, another obscure footnote was released about the state of the Japanese Navy.

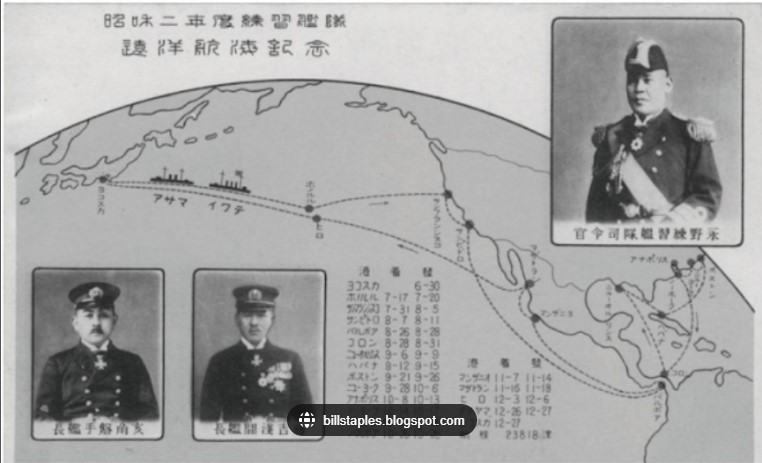

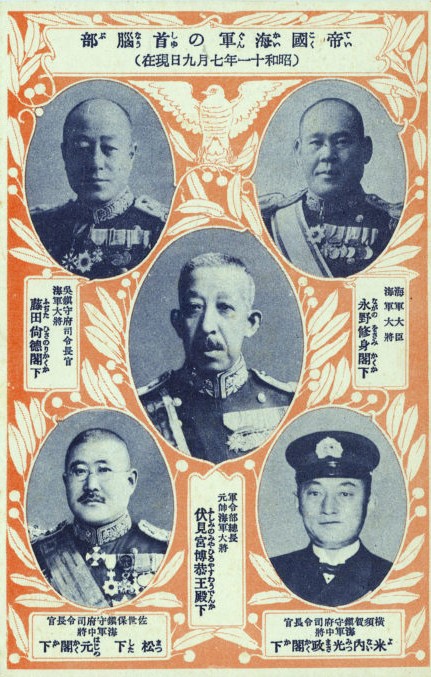

Captain Nagano, Naval attaché from the Japanese admiralty office informed the press that he had received a cablegram from Japan that all Japanese naval vessels and personnel of the navy department were safe. The main fleet had been at sea or in other areas during the quake and its aftermath and had escaped harm according to the reports. Captain Nagano would leave the United States and return home to Japan in December where he would be promoted to Rear Admiral. He would return a number of times to the United Stated over the next few decades and have a very strong opinion about the wisdom of engaging the US in wars. Despite his reluctance, Nagano would play a key role in the life of Cassin Young when less than two decades later he would order the Imperial fleet to carry out the most significant order ever given. One of the Japanese ships sent to help with the recovery work was the battleship Hiei. Along with her would be the battleship Kirishima.

On the same day Nagano released his report on the state of the Japanese fleet, reports surfaced in the Washington press about the ongoing concerns by American naval strategists in regards to the actual state of the Imperial Navy and its resources. The recently signed Naval Arms Limitation Treaty had provisions in it that allowed participating members to replace lost or damaged vessels with “similar class and function” vessels. This provision might actually work to Japan’s advantage since ships that were older or less capable could rapidly be replaced by newer ships with improved weaponry and propulsion. Even with a strategic inferiority imposed by the treaty, Japan’s navy could surreptitiously make advances in its naval capabilities both at sea and on shore. This weakness of the treaty was only one of many that would be revealed over the coming years. Almost from the start, both sides of the Pacific had proponents of testing the limits of the treaty. Despite the short term good will that was gained by the Americans in the aftermath of the tragedy, the reality soon returned. Japan needed to expand its territory in Asia and America was the most immediate threat in preventing them from achieving that goal.

Another provision of the treaty that would have long lasting effects was Japan’s insistence that the western powers would be limited in how many and what kind of improvements could be made to islands and bases in the Pacific. Since the treaty placed Japan in an inferior position in regards to overall tonnage and size, the bargain that was reached limited America and Britain in how many bases and improvements could be made. In 1922, the idea that a large invasion force could quickly sweep through the island chains of the western Pacific must have seemed remote. The realities of what actually happened in 1941-1942 are proof that the provision of limitations was short sighted and of deadly consequences. As island after island and country after country fell, the remaining men who crafted the treaty must have felt enormous regret.

The aftermath of the quake brought many changes to Japan.

There had been rumors of Koreans that lived in Japan poisoning wells and killing Japanese in revenge for their circumstances. The rumors led to mass hysteria in some cases and resulted in the death of an untold number of Koreans and others from the nearby countries. The Japanese police and military were mobilized to reign in the mobs. The attitude of the government hardened noticeably against foreigners and the army gained a greater share of power.

Click to access Kanto%20Massacre%20Booklet%20in%20English%20Translation.pdf

Crown Prince Hirohito was already leading the country in the early 1920’s as his Uncle slowly failed in health. He was actively engaged in the Four-Power Treaty on Insular Possessions signed on December thirteenth 1921. The nations of Japan, the United States, Britain, and France agreed to recognize the status quo in the Pacific, and Japan and Britain agreed to terminate formally the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. The Washington Naval Treaty was signed on February sixth 1922 would further solidify Japan’s ranking among the world’s powers. Japan withdrew troops from the Siberian Intervention on August twenty eighth 1922. After the Great Kantō earthquake devastated Tokyo, Hirohito escaped assassination by Daisuke Namba in the Toranomon incident. After the failed attempt, Namba claimed to be a communist and was executed. Some historians have suggested that he was in contact with the Nagacho faction in the Army. The Emperor Yoshishito died on December twenty sixth of 1926 and Hirohito was elevated to the throne.

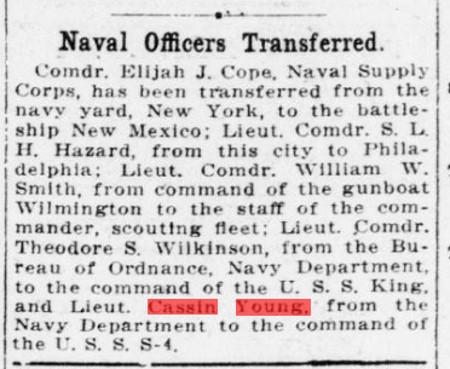

Lt. Cassin Young’s tour in Washington would only last two years.

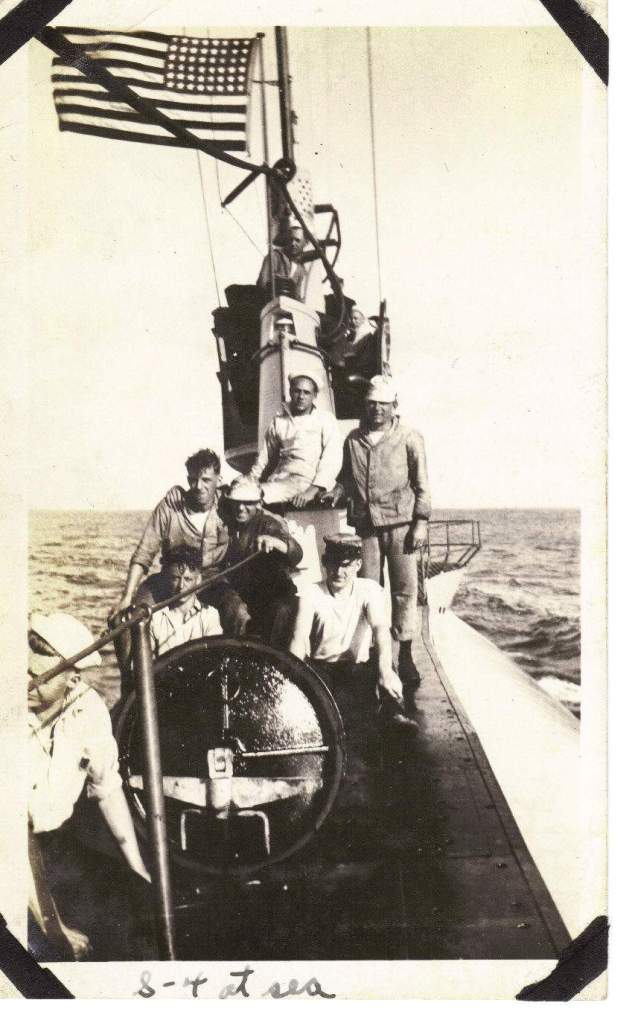

In January of 1925, he was headed to the west coast to command the S-4 which operated out of Mare Island with the Pacific squadrons.

The training missions would take them from San Francisco to San Diego as the submarine force made its adjustment to the west coast. Lt. Young would soon be promoted to Lieutenant Commander as he transitioned to the staff of the Submarine Division of the Battle Fleet. During the nineteen twenties and nineteen thirties, the submarine force would continue to struggle with technical difficulties and attempts to solidify their place in the fleet.

The S-4 would return to the east coast without Young and tragically be lost in another unfortunate collision. This would be the second time Cassin Young would escape a watery death. The USS S-4 submarine sank with all hands on December Seventeenth, 1927.

1928-1929 “Air getting very bad. Please hurry,” and finally, “Is there any hope?”

From the “Loss of the S-4”

“running submerged just off the coast of Provincetown, MA, conducting speed and maneuverability tests between the two white buoys that marked the beginning and end of a measured nautical mile. Meanwhile, on the surface, the Coast Guard destroyer USCGC PAULDING (CG-17) was headed southeast, making 18 knots as she searched for rumrunners carrying their illegal product across the bay to thirsty buyers in Boston. At 3:37 in the afternoon, as S-4 began to surface, the officer of the deck aboard PAULDING, scanning the surrounding seas through his binoculars, spotted the telltale wake of a periscope close aboard on the port bow. “Hard astern! Full right rudder!” came the order, but not fast enough. PAULDING rammed the sub, a section of her bow telescoping into S-4’s hull and punching two holes, one in a ballast tank and one in the pressure hull. Freezing water flooded into the boat, causing her to heel to port and begin to sink by the bow. PAULDING’s crew immediately marked their position on a chart and radioed their superiors. When the destroyer came to a halt, one of her lifeboats was lowered over the side. All it found was a small oil slick, which the men aboard marked with a buoy.”

The boat sank in part of the channel that was not all that deep – 110 feet. But the collision cause much damage so quickly that the crew had to evacuate the control spaces and gather in an after compartment. That sealed their fate.

When the boat was finally brought to the surface the following year, divers found the aft spaces to be practically dry—it was the air that had killed the men, not the water. According to an article in the New York Herald Tribune written on 19 March 1928, the body of Lieutenant Commander Roy H. Jones, commander of S-4, “was found at the foot of the stairway, indicating he stood alert until overcome.” Divers also “found a spectacle that moved them, hardy and inured as they are to horror, to deep emotion. Near the motors, arms clasped tightly about each other in protecting embrace, were two enlisted men, apparently ‘buddies.’ The divers tried to send them up thus locked together, but the hatch was not wide enough and they had to be separated.” Some of the men had lived long enough to grow hungry—two had half-eaten potatoes in their pockets. Divers also noticed that “the walls were battered and scarred by many heavy blows and one spot indicated that an attempt had been made to cut through with a cold chisel.”