Chapter Fourteen – Facing Far East

In the 1920’s, the battle between the Navy, Congress and the Executive branch played out in the newspapers and around the globe. The Naval Disarmament Treaty of 1922 expedited the cuts that the professional Navy observers had long feared. Many existing ships were scrapped, new construction slowed to a crawl and technical advances were only begrudgingly gained. The Navy had already sensed that the changes were coming and in the summer of 1921, made some fundamental changes to the placement and strategy of its fleets. The Atlantic had long been the primary body of water where fleet practices were undertaken. The major cities on the east coast had gone through a period of increased anxiety during the Great War because of the potential threat of the German fleet and its dangerous submarines.

But the Navy was looking to the Far East for its next challenges.

The Japanese had already been expressing their frustration with official policies meant to limit their expansion. Military leaders bristled at the idea that a far-away nation like the United States could dictate terms to them in areas where they felt they had a more natural advantage. Geographically, that was very close to the truth. The Philippines had been a protectorate of the United States since the early 1900’s and the calls for independence were constant.

United States Military strategy had always assumed that we would be able to reinforce our garrison there in the event of Japanese aggression. But the distance between the home islands of Japan and America’s west coast made the argument questionable.

In July of 1921, the US Navy redesignated the Pacific fleet to the Battle Fleet and the Atlantic Fleet to the Scouting Fleet.

This designation meant that important assets would now be shifted to the west coast and that bases and facilities would need to be bolstered. From San Diego to the Puget Sound, the West Coast would now become the primary places where ships would operate from and receive much needed repairs between journeys. The sleepy little coaling base at Pearl Harbor gained value as well since the coal ships had nearly all been replaced by oil burning ships that went further and faster on less fuel. The natural harbor at Pearl was considered to be a very safe place for ships to rest and be worked on. The location was perfect for an American surge in case of any Japanese aggression.

None of this escaped the attention of Japanese planners.

The Japanese had gained holdings in the Pacific region as a result of the end of the Great War. Part of the agreement of 1922 was that further bases would not be built or fortified. The same agreement made provisions that inspectors from each of the signatory countries could go to those existing bases and conduct inspections. Reports at the time indicate that the Japanese were not as cooperative as the treaty had spelled out. One Naval Attaché in Japan reported that he had been to all of the major naval bases, but the hosts had successfully brushed off any attempts to see anything significant.

Lt. Cassin Young arrived at the Navy Department in Washington DC on January 23rd, 1923, and probably had a front row seat to much of what was happening.

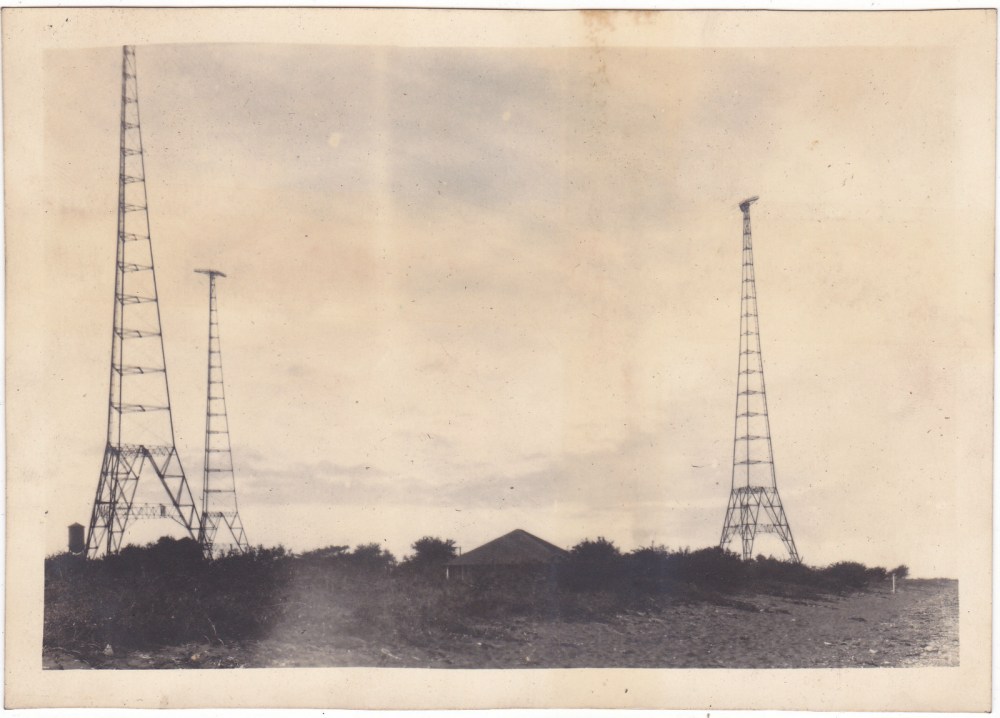

His work at Naval Communications would certainly be impactful on any future conflicts.

Wireless communications had grown significantly in the entire fleet, and the country was in the midst of a communications revolution by the early nineteen twenties. A little over twenty four years had passed since the Spanish American war had been fought. While wireless was in use around the world, the range and efficiency of wireless communications were very limited by the technology available at the time. In order for the American fleet to communicate over long distances, smaller craft had to shuttle the information updates to nearby friendly ports where they could be transmitted by wire to the authorities in Washington. Communications between the Navy and the Army units deployed ashore were also reliant on a system based on written messages that had to be transmitted at great risk to the persons carrying the messages.

The World War certainly brought some advances, but the use of radio in communicating was still in its infancy. It wasn’t until the nineteen twenties that radio started really growing in its capabilities. New developments including the vacuum tube brought the science of radio communication to an entirely new place and the Navy was quick to recognize the importance of this technology.

The 1924 textbook on naval communications written for the Naval Academy gives a good accounting to date of the advances in the previous years.

In the beginning of the book, Lt. Alexander Kidd explains that the Navy communications policy include the following:

“To maintain and operate a Naval Communications System based on the requirements of the forces afloat in a campaign in either or both oceans

To provide adequate radio communications facilities to marines along the United States coasts where privately owned facilities are not made available

To provide harmony and cooperation between Naval radio systems, and all other radio systems and to define the areas of their activities.

To watch and guard the radio and cable interests in the United States

To provide radio compass stations as required.

To develop and coordinate all systems and methods of communication which efficiently transmit information.

To develop within the Fleet, the uses of all forms of Communication required for battle efficiency

To use the Naval radio communication system in time of peace to assist in the development of American interests abroad.”

Communications would become the ultimate weapon both offensively and defensively as the opposing forces on either side of the Pacific grew in numbers and strength. The Japanese expansion efforts would rely heavily on being able to direct ships and in the future aircraft to the places where they would be of the most use. The Americans also saw the value in this extended form of communication offensively and spent an almost equal amount of time developing capabilities in overcoming any offensive use. This would include learning ways to listen to the enemy’s communication, interpret their purposes and help American forces to respond more effectively. The ability to manage communications in the theater was important for directing large ships movements. The ability to communicate more quickly and with greater efficiency between ships in an actual battle would be the difference of life or death.

The importance of the Naval Communications department was highlighted in a message in June of 1923 reported in the Washington Evening Star. “The commander in chief considers the service rendered by the communications office of the Navy Department excellent and an improvement over last year.” Messages from the Far East still had to be “relayed” between the far flung stations via naval bases that were so equipped. In this instance, a message sent from Cavite (in the Philippines) was relayed through Pearl Harbor via San Diego in less than two minutes which constituted a new record. The realities of the day were that atmospheric static and equipment that was still in its infancy made this the exception rather than the rule. Something called “the static season” still interfered with effective transmission and cables still ended up being the primary means of communications.

During the Inter-War Period, the large fleet consolidated first in 1919 into two equally-sized Atlantic and Pacific Fleets to prepare to counter either Great Britain or Japan and then in 1922 into a single United States Fleet largely based on the West Coast to counter Japan. Avoiding forward deployments that were perceived as provocative, the U.S. Fleet focused on annual fleet exercises and experiments near the United States. The fleet was only deployed forward once this period, to Australia and the southwest Pacific in 1925, which elicited significant criticism from Japan.

Life in the District of Columbia for a Navy family in the nineteen twenties would have been a welcome change from the smaller and more remote stations they had lived in prior to their point. The Young’s had gone from Connecticut to the Canal and back before finally being allowed to join the exclusive assignments of Washington. The family of three (Cassin, Eleanor and Charles) had grown in the past few years as well. Daughter Eleanor had joined the family in August of 1922 and would soon be joined by daughter Maryann in October of 1923.

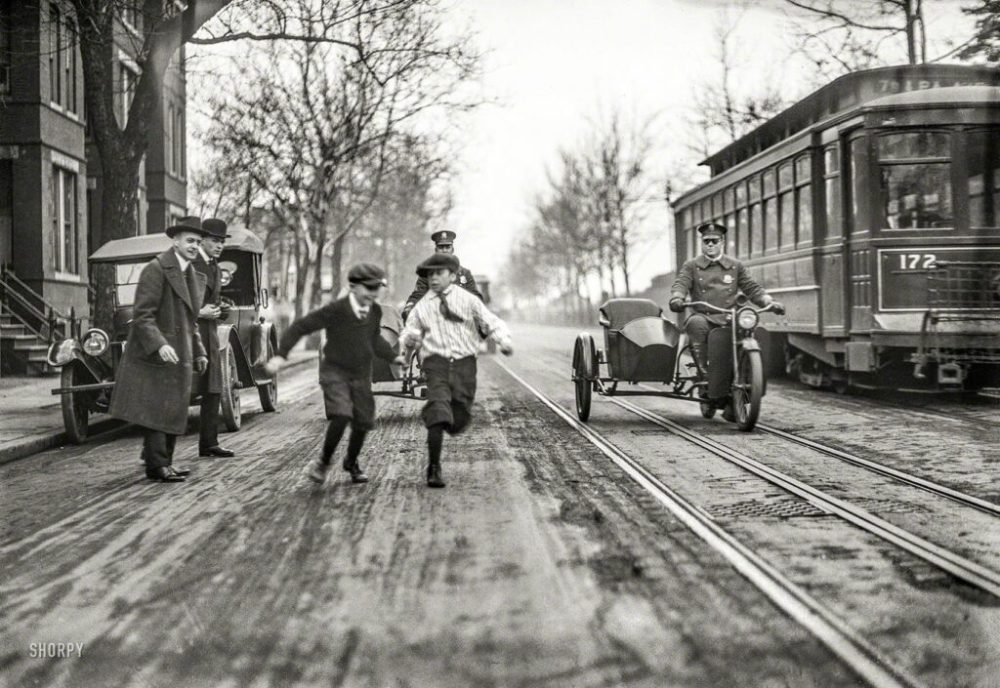

Many things had changed in the district since Cassin was a young boy. At the turn of the century, horse drawn wagons still filled the streets (many which were poorly paved) and buggies were one of the ways that people traveled from place to place. By the early 1920’s, national prosperity and the availability of the automobile were responsible for crowding the old ways out. In November of 1923, the Evening Star reported that engineers and architects were realizing that cars were quickly outgrowing the average city and alternatives that were safer and faster would son need to be found. Interestingly enough, the writers felt that personal airplanes could be the answer. No mention was made about where they would take off or land. At the same time this vision was being suggested, the Police Chief of the District was urging people to be aware of the dangers of the “Machines” which could bring death and destruction to the careless in a very short manner. Signs of caution and warning seemed to have little effect on controlling the habits of careless drivers. The Chief stated there were two categories at the root of the problem. “The reckless driver, who does not feel any responsibility for the lives of others but simply drives his own machine to suit his own selfish convenience.

“And the citizen who either ignorantly or carelessly crosses streets without first seeing if it is safe to do so.” The Safety committee of the District was spending a lot of time examining how these two issues could be controlled.

In Panama, shopping was limited to once a day and fresh food spoiled quickly in the tropical climate. In the District, Mrs. Young would not be limited to any particular day and could buy whatever their budget allowed. Once home, much of the perishable food could be stored in a modern ice box that had compartment for ice but was built with much higher standards than earlier models. In 1923, Frigidaire introduced the first self-contained unit. Roughly at the same time porcelain-covered metal cabinets began to appear. Ice cube trays were introduced more and more during the 1920s; up to this time freezing was not an auxiliary function of the modern refrigerator.

Shopping was done at neighborhood markets, but the birth of larger markets was also becoming a way to provide for the family’s needs. The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company stores (A&P) allowed shoppers to increase their buying power by pricing their goods in a way that would attract shoppers for all their needs. The A&P ads read that “WE ARE able to sell high grade groceries at lower-than-other’s prices, because of our unique advantageous position as the largest grocery house in the world.” The availability of many food choices and the cost-efficient process added much to the era of consumption we now call the Roaring Twenties.

As the Youngs were enjoying their life in Washington, around the world an event occurred in September of 1923 would have grave consequences and stimulate the conditions that would eventually lead to a clash between the United States and Japan.

The Great Kantō earthquake struck the Kantō Plain on the Japanese main island of Honshū at 11:58:44 JST (02:58:44 UTC) on Saturday, September 1, 1923. News cabled across the Pacific indicated that the duration of the earthquake was between four and ten minutes. The impact would be felt for much longer.

One of the ships that was sent by the Imperial Fleet to assist with the disaster was the battleship Hiei.

The Hiei had been designed by British naval architect George Thurston. She was the second launched of four Kongō-class battlecruisers, among the most heavily armed ships in any navy when built. Laid down in 1911 at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, Hiei was formally commissioned in 1914 when Cassin Young was still a midshipman. She patrolled off the Chinese coast on several occasions during World War I and helped with rescue efforts following the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.

Starting in 1929, Hiei was converted to a “gunnery training ship” to avoid being scrapped under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. The Japanese people had balked at the inferior ratio they were forced to accept in the 1922 Treaty of 5:5:3. In fact, leaders were assaulted during the numerous riots in Tokio after the treaty terms became known. So this subterfuge was a way to game the system.

She served as Emperor Hirohito’s transport in the mid-1930s. Starting in 1937, she underwent a full-scale reconstruction that completely rebuilt her superstructure, upgraded her power plant, and equipped her with launch catapults for floatplanes. Now fast enough to accompany Japan’s growing fleet of aircraft carriers, she was reclassified as a fast battleship. She sailed as part of Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s Combined Fleet, escorting the six carriers that attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. She would sail all the way through November of 1942 when her fate and that of Cassin Young would intertwine on the night of Friday the 13th.