“Information from other sources sheds rather a different light on the matter.” Underestimating any enemy can be dangerous.

Recently, I was browsing through the national archives and found some declassified documents dating back to the 1920’s about submarine development abroad. During that time frame, there was a great desire on all parts of the world to limit arms and particularly battleships and all types of seagoing warships. The cost of the Great War was still bearing down on the economies of all of the participants, so stemming the flow of money into warships was an easy decision. Unfortunately, this savings did not take into account the nature of the nations involved to want to continue their domination of the seas in both commerce and arms.

Reports at that time about the Japanese navy were fairly negative.

International observers were claiming that the Japanese were falling behind their global navies in a number of areas. This was an era where battleship technology was slowly being usurped by air and undersea weapons. Communication technologies in the 1920’s included radio advances around the globe and it appeared as if the smaller nations would not be as adaptable to their counterparts in the west. But the Japanese had other ambitions in their part of the world. The leadership had long since acknowledged its need for resources beyond its borders and becoming a global power would men having free access to these resources. Even feeding the nation required commerce outside of the island chain that was their home. Expansion was not just about nationalism, it was about survival.

One of the documents I discovered in the archives was a previously designated top-secret report on Japanese activities in Switzerland dated 14 January 1921.

The source for the information was a confidential source which asked for identity protection. That person was only identified as an engineer in the service of the Sulzer Brothers, a Swiss manufacturer of diesel engines (among other mechanical devices). The source relayed the conversation and information garnered from conversations with Japanese Officers who were in post war Europe to obtain technical information and much more. Interesting observation about the source: since the company that they worked for was in many ways a direct competitor for the firms identified in the report, one has to wonder what the real motivation for divulging the information was.

Again, this is in 1920-1921 and Germany had already been defeated by the allied powers.

- During the past year, there have been in Switzerland a large of Japanese naval commissions that have been in communication with various firms in Switzerland and who have proceeded to Germany.

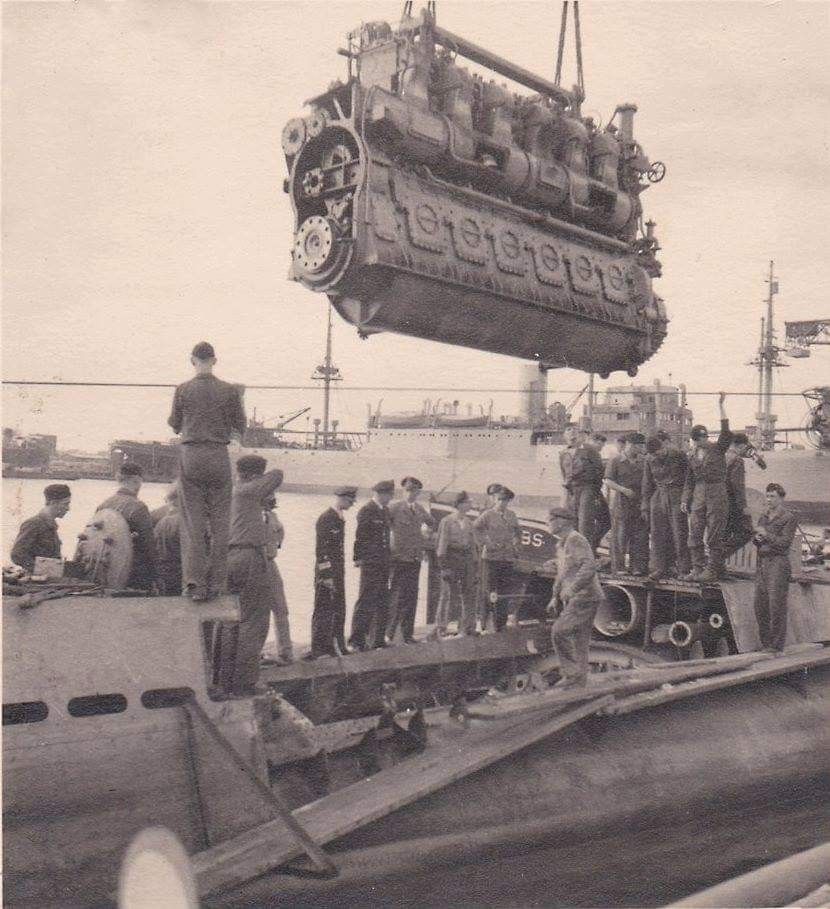

- An interesting fact, for instance, is that the firm of KRUPPS have made proposals for the construction of new large submarine engines to the Japanese Navy, probably also other German manufacturers of submarine engines are making the same proposals, which is evidence that German firms do not intend to suspend the construction of submarine engines as required by the treaty. In one specific instance, a contract for submarine engines which was going to be signed was postponed because at the last moment, the German firm Machine Fabrik Augsburg, Nuremberg very considerably underbid the Swiss firm

- In conversation with a Dutch officer, as well as with Japanese Naval Officers, on this subject, the above stated that there was no difficulty in obtaining these submarine engines from the German manufacturers not around its provisions; one, in particular being simply a change in the designation of the engine – – instead of selling the type desired as a submarine engine, they are sold as “stationary engines”.

- Another way suggested by the Dutch officer was the manufacture of the engine and parts and their shipment to Holland and erection after arrival there. It is known that Fischer and Company of Schaffhausen who make casting for submarine engines, are making large numbers of parts and shipping them to German, for instance to the “M.A.N.”, Dautz, Daimler and others. A member of the Japanese Commission stated laughingly that such orders could always be placed through a second party

- Two facts are certain: the Japanese Navy is buying large numbers of submarine engines in Switzerland and in Germany, and is also building some in Japan having purchased the licenses to construct the latest types in Switzerland, Italy and England. The other is that the Germans are making very large quantities of submarine engines in defiance of the Treaty. About these two facts there is no doubt.

Meanwhile, in the United States, submarine design and engineering was still mired in bureaucracy and slowed by the manufactures and their adherence to imperfect designs. The navy leadership was aware of the powerful influence of a long-distance sea going submarine. The Germans had aptly demonstrated that with their U boats during much of the Great War. Our early lack of a credible antisubmarine warfare structure caused the loss of too many ships and too many lives. It was only the sheer magnitude of our ability to manufacture replacement shipping as well as develop early forms of antisubmarine warfare that turned the tide.

But without the magnitude of the defeats on land, the German Navy could have continued on. With the surrender of the fleet, her war making efforts ceased. But her ability to make machines did not.

The American Navy did come into possession of five German U boats after the war. These boats were studied but the ability to change course within the building structure was still hampered. This delay in making needed changes would be evident in the coming decade.

American Submarines in 1927

From: Navies and nations; a review of naval developments since the great war, by Hector C. Bywater (1927)

At the beginning of 1927 the submarine flotilla consisted of 129 boats, not including five under construction or projected. Only sixty of these, however, are sufficiently large and seaworthy to be employed on ocean – going duty, the remainder being small boats of 520 tons or less whose sphere of utility is limited to coast defense. Of the larger boats, fifty belong to the ” S ” class, with an average displacement of 900 tons, a surface speed of 14 knots, and a cruising endurance of 5000 to 8000 miles. Three ” fleet submarines, ” T1 – T3, of 1100 tons and 20 knots, were completed in 1924 but proved unsatisfactory and have had to be fitted with new engines. The latest vessels are submarine cruisers of the ” V ” class, designed for duty with the Fleet. In the first three the displacement is 2164 tons and the speed 21 knots, but the boats now under construction will approach 3000 tons. They are powerfully armed with guns and torpedoes. One is equipped as a minelayer, with a capacity of 60 mines.

In the Fleet Commander-in-Chief’s report already quoted the following judgment was passed on the submarines engaged in the maneuvers: ” Of the combatant ships taking part in the problems the submarines are the worst.

Their design is obsolete and faulty. Their ventilation is poor, and at times almost non – existent. The temperature in the engine- room rose as high as 135 degrees. They are unreliable, some of their fuel tanks leak, either spoiling their fresh water, or enhancing the fire menace, or leaving an oil slick ‘ whereby they can be tracked. The radius of the Holland boats is much less than rated and they drag excessively when loaded. All the submarines are so deficient in speed as to be of small use for fleet work except by accident of position. They must be used with the fleet, either so far ahead as to be out of the way, in which case they are a source of worry, or assembled astern, from which location they cannot gain an effective position in case of contact. There is no doubt that all save the newest American submarines are lacking in speed, contemporary British and Japanese boats being much faster. Further, their radii of action seem to be unduly restricted, a drawback the more serious in view of the strategic conditions under which they would have to operate in war. Next to cruisers, large submarines of good speed and great endurance would appear to be the most pressing requirement.

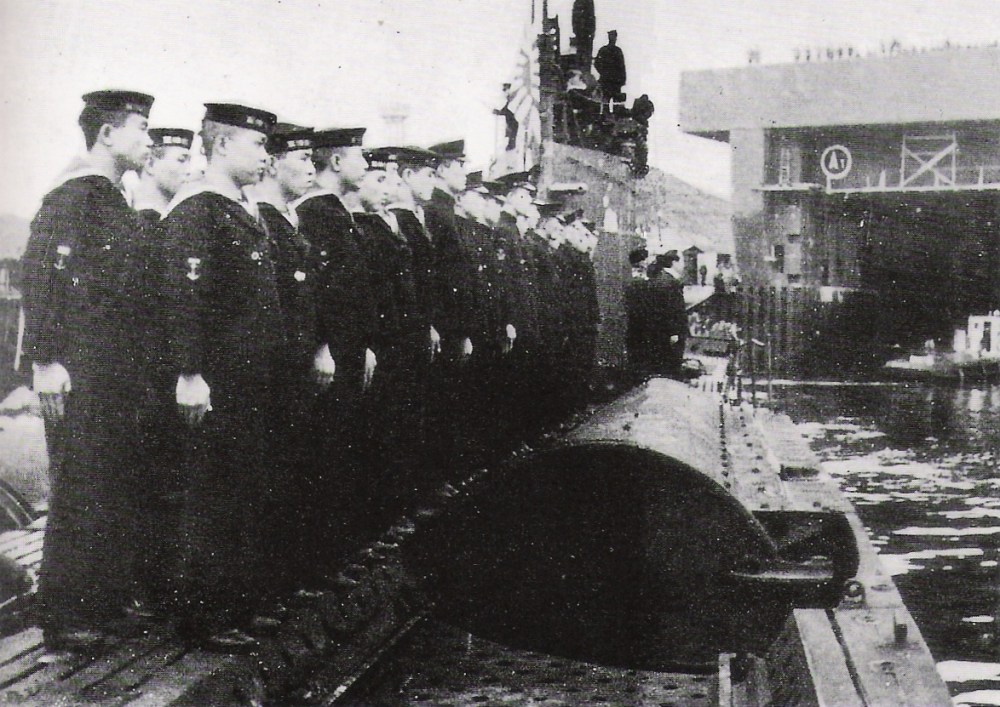

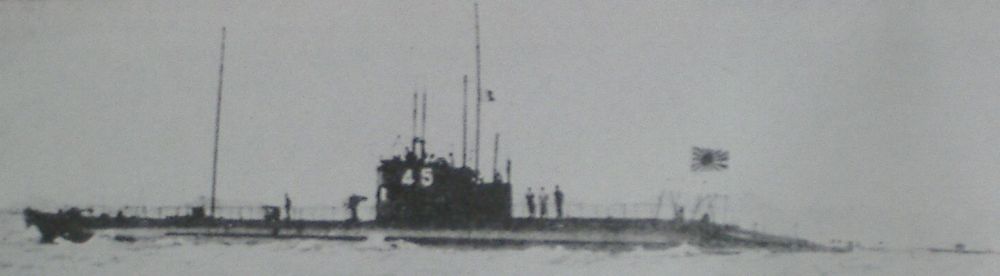

The Japanese were slow to take an interest in submarines but after the Russian war of 1904, they took swift action, ordering Holland 1-5 from Fore River Yard, Quincy USA. These were shipped to Yokohama and reassembled, remaining in service until 1922. The Japanese built tow more #6 and 7 which were built by Kawasaki using the lessons learned from the first five. The follow-on classes were primarily built using established designs from other countries. But the German engines and equipment made the biggest leap forward.

From the same report: Japan and Her Fleet

Remarkable progress has been made with the development of the submarine force. Eight years ago, it consisted of a limited number of small boats of doubtful efficiency, incorporating what were supposed to be the best features of British, French, and Italian practice. Today Japan has more ocean – going submarines than any other Power, and her latest craft are believed to be unsurpassed for reliability. Among them are improved editions of the German submarine cruisers built in the later stages of the war, of which Japanese experts made a thorough examination. While full details are impossible to obtain, the following is believed to be an authentic summary of the present flotilla:

Eight submarine cruisers, 2100 tons, speed 23 knots, two 4.7 – in. or 5-5 – in. guns, six torpedo tubes. Actual cruising endurance, 11,000 miles. Two of these were completed in 1926. The other six should be ready by the end of 1928. At least two are minelayers, with a reduced number of tubes and a supply of 60 mines.

Fourteen oceanic submarines, 1200 to 1500 tons, speed 20 knots, one 4.7 – in . gun, six torpedo tubes. Cruising endurance 8000 miles. Three of these are minelayers.

Twenty sea – going submarines, 900 to 1000 tons, speed 17-18 knots, one 12 – pdr . gun, four to six torpedo tubes. Cruising endurance 6000 to 7000 miles. Some of these are fitted for carrying mines.

Twenty – six sea – going submarines, 700 to 750 tons, speed 17-18 knots, one 12 – pdr . , six torpedo tubes. Cruising endurance 5000 miles.

Seven coast – defense submarines, 300 to 450 tons, speed 14-16 knots; no guns, two or four torpedo tubes.

A few older boats of small fighting value, used only for training purposes.

Japan, it will be seen, has no less than twenty – two submarines larger than 1000 tons, built and building. Of corresponding boats, the British Empire has only thirteen and the United States no more than six. Moreover, the Japanese submarines have a higher speed average than the British or American boats, and their cruising endurance is believed to be greater. In this type of vessel Japan has undoubtedly gained a considerable lead over all other countries.

During 1922-24 a series of disasters, involving the loss of several boats and many lives, led to doubts being expressed as to the efficiency of Japanese submarines and the competence of their crews. A certain feeling of insecurity existed among the officers and men engaged in this service was made evident by the action of the Navy Department, in April 1924, in inviting officers attending the submarine training school at Kure to submit unsigned statements of their views on this question. The response is said to have been eminently satisfactory, one and all expressing their complete confidence in the new boats and their eagerness to serve therein. There is not the least doubt that the submarine branch of the Japanese Navy is efficient, highly – trained, and formidable. In an address delivered in London a few years ago Baron Hayashi, the former Japanese Ambassador, quoted foreign experts as having observed that the physical and mental strain of submarine duty was felt less by Japanese sailors than by Europeans, and that Japanese submarine crews were able to remain at sea for much longer periods than crews of any other race.

The last part of the Japanese Navy section of the report was very interesting considering the fact that Japan was less than fifteen years from engaging in the largest naval warfare in its history:

At the end of the Great War and for at least five years thereafter the Japanese Navy was inferior in technical equipment to the navies of Britain and the United States. This was due to several causes, but principally to lack of first – hand experience of the great advance in tactical methods – gunnery, torpedo, mining, anti – submarine devices, wireless, etc. – which had been achieved during the war. As late as May, 1925, the correspondent of The Times in Tokyo wrote that ” in gunnery control the Japanese, for want of external assistance, have come to a virtual standstill and are fast losing ground. They can know little about the latest methods of long – distance firing and indirect firing. As for aerial co – operation, their communication between Aeroplanes and ships is, at present, believed to be so poor that it is doubtful whether they could efficiently utilize aerial fleet reconnoitering at all. ”

Information from other sources sheds rather a different light on the matter.

For example, one of the European naval attachés who visited the gunnery school at Yokosuka in 1924 was impressed with the up – to – date methods of training in vogue. Again, in the fleet maneuvers of 1925 all ships took part in long – range firing practice, and aircraft were freely employed for spotting ” duty. Photographs of Japanese battleships and cruisers show them to be equipped with range – finders and other gunnery control instruments of modern pattern. In view of this evidence reports of the Navy’s backwardness in gunnery or any other branch of war training should be treated with reserve. It is conceivable that Japan, for reasons of policy, does not wish the world to form too high an opinion of her naval strength, in which case the somewhat pessimistic rumors which sometimes gain currency would be explained.

The game changer for Japan was recognizing that continuous improvement was the key to succeeding.

Engines and technology bought from Germany and others during the prewar years was the game changer. The role of the Japanese submarine force is rarely talked about since they were the vanquished nation. But their impact was felt in too many ways. The enormous industrial power of the United States was once more the game changer in the overall outcome of the war. But the tremendous threats of the Japanese submarine force made sure that every ship had to expend time and energy guarding against attacks from a very capable threat.

Every convoy inarguably lost precious time and energy countering the threat of this menace. Some incredibly powerful examples of the threat include carriers and cruisers that fell into the path of efficient undersea warriors.

Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) submarines formed by far the most varied fleet of submarines of World War II, including manned torpedoes (Kaiten), midget submarines (Kō-hyōteki, Kairyū), medium-range submarines, purpose-built supply submarines (many used by the Imperial Japanese Army, see Type 3), fleet submarines (many of which carried an aircraft), submarines with the highest submerged speeds of the conflict (Sentaka I-201-class), and submarines able to carry multiple bombers (World War II’s largest submarine, the Sentoku I-400-class). They were also equipped with the advanced oxygen-fueled Type 95 Torpedo (which are sometimes confused with the famed Type 93 Long Lance torpedo).

Overall, despite their advanced technical innovation, Japanese submarines were built in relatively small numbers, and had less effect on the war than those of the other major navies. The IJN pursued the doctrine of guerre d’escadre (fleet vs fleet warfare), and consequently submarines were often used in offensive roles against warships. Warships were more difficult to attack and sink than merchant ships, however, because naval vessels were faster, more maneuverable, and better defended.

History Belongs to the Victors

In the United States, we have many books written about our submarines and the valiant stories which were often made into movies. Japan has little of that. Again, the vanquished rarely get to speak. But looking at the history of how they developed is important for us as a country.

The Japanese submarine force is now using new technologies to power her small force.

The introduction of the Type 12 long-range cruise missile will be paramount for the JMSDF.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has been contracted to mass-produce long-range cruise missiles for Japan’s submarine fleet. According to a press release, Japan’s Ministry of Defense announced these twin contracts for the upgraded Type 12 anti-ship missile and the unnamed torpedo-tube-launched cruise missile. This announcement comes as Tokyo continues to bolster its defensive tactics amidst rising hostilities from Beijing and Pyongyang. “The Ministry of Defense and the Self-Defense Forces are strengthening their stand-off defense capabilities in order to intercept and eliminate invading forces against Japan at an early stage and at a long distance,” Japan’s Ministry of Defense stated, adding that “In order to quickly build and strengthen this capability, they are currently working to acquire domestically produced stand-off missiles as soon as possible.”

New diesel engines

Until the third Taigei-class submarine Jingei, two Kawasaki 12V 25/25SB diesel engines were used as the main engines, but Raigei started to use new Kawasaki 12V 25/31 diesel engines with a high output power for the first time. These new diesel engines are compatible with a new snorkel system with enhanced power generation efficiency.

The Taigei-class is powered by a diesel-electric engine generating 6,000 hp. It has a maximum speed underwater of 20 knots.

Lithium-ion batteries

The JMSDF said that the Taigei-class is equipped with lithium-ion batteries in place of lead-acid ones, just like the final two Soryu-class boats for the JMSDF: Oryu (SS 511) and Toryu (SS 512).

GS Yuasa, a Kyoto-based developer and manufacturer of battery systems, provided the lithium-ion batteries for those new submarines. So far Japan is the only country known to have fitted lithium-ion batteries into SSKs, with South Korea expected to be the next country to do so with three 3,600-ton Jang Bogo-3 Batch 2 submarines. These vessels are scheduled to be commissioned from 2027.