Everybody needs heroes.

You know, a bigger than life person that stands out among other people. Someone who lives a life of adventure and leads others through periods of adversary and innovation.

The kind they write books about.

When I was a kid, it was Horatio Hornblower. Hornblower was the most memorable character in a series of book written by C. S. Forrester. Cecil Louis Troughton Smith (27 August 1899 – 2 April 1966), known by his pen name Cecil Scott “C. S.” Forester, was an English novelist known for writing tales of naval warfare, including the 12-book Horatio Hornblower series depicting a Royal Navy officer during the Napoleonic Wars. I read every one of the books at my school library and I am sure that had as much to do with my dream to become a sailor as my family heritage. Maybe more. I have always had an overactive imagination, and I am positive that I felt myself on the bridge of every ship he sailed on.

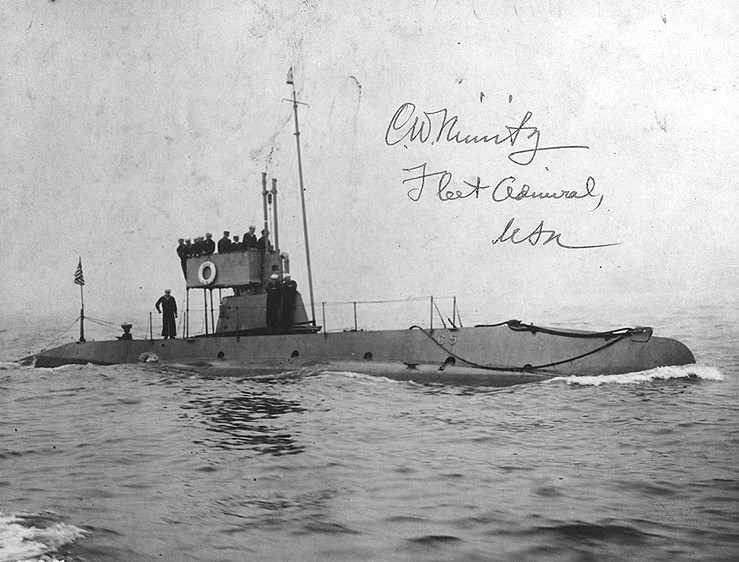

The submarine force of the US Navy also had its own Horatio Hornblowers in the early days of development. Chester Nimitz (Class of 1905) comes to mind as does C M Lockwood (Class of 1912). Early on, men like these dared to ride the small submersibles through the changes that would follow. From the incredibly dangerous gasoline powered craft to the sleek fleet boats that would help tip the scales of victory in the Second World War, the evolution of submarines was pushed through by the sheer will of the men who drove them. They did this despite the incredible hear winds of the battleship admirals who saw the tiny boats as a mere distraction and something which syphoned off precious dollars from more important things.

One hero (who probably never thought of himself as a hero)) was a trailblazer that never got the recognition for his part in the submarine story. His name was James Reid Webb (Class of 1913)

James R Webb – an American Submarine Hero

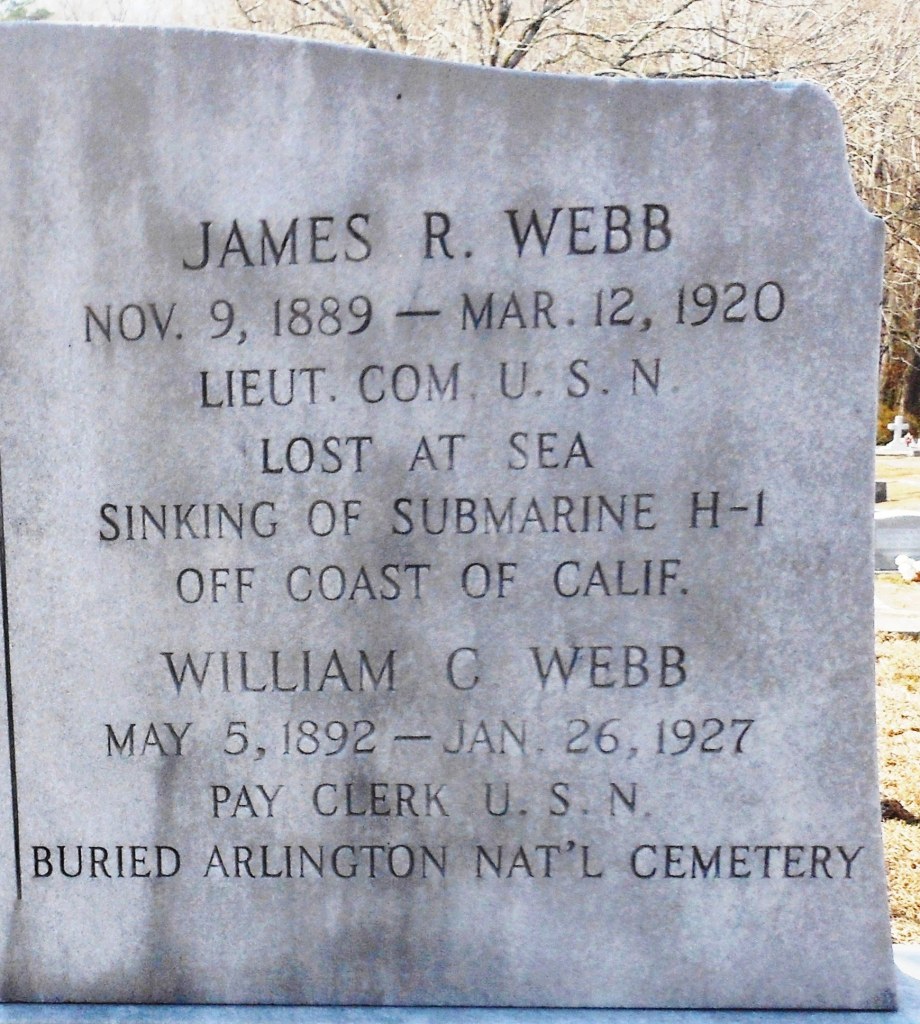

James R. Webb was born on November 9, 1889, in Seneca, Oconee County, South Carolina To James and Elizabeth Webb. His father James was a clerk on the Southern Railroad. His brothers were William, a pay clerk in the Navy, and Joseph. WC Webb was a Warrant Officer during the first world war and Joseph Webb would later rise to the rank of Captain in the US Navy. Joseph was an enlisted storekeeper before becoming an Ensign. Interestingly enough, the grandfather (Elizabeth Reid’s father) was an officer in the Confederate forces of the late war.

From researcher Kathy Franz:

James was commander of the First Battalion, Company I, at Central High School. In December 1907, James, as a high school cadet, was a guest at a charity ball at the Arlington Hotel. The Secretary of the Navy and many ambassadors and ministers were in attendance.

On February 22, 1908, he was commander of the First Battalion in the parade honoring General Washington’s 176th birthday in Alexandria, Virginia. Earlier that month, his company sponsored a school dance at the Arlington Hotel.

The Washington Times reported March 15, 1920 that:

Commander Webb attended Central High School and was major of the cadet corps there. At his graduation in 1908 he was considered the most popular man ever graduated from that institution. He served a year in the revenue cutter service and later attended the Navy Academy at Annapolis, from which he would graduate in 1913.

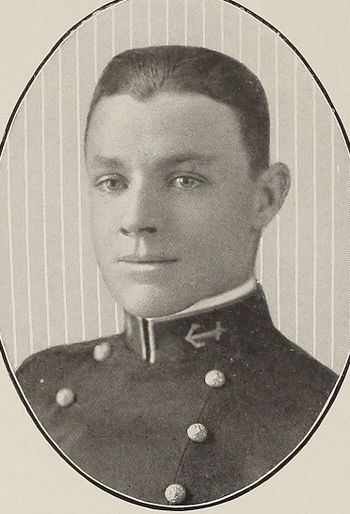

His peers recognized what a distinctive character he was at the academy. Every year, the graduates are panned in the Lucky Bag, a form of yearbook for the academy. This is the entry for James.

James Reid Webb

Washington, D.C.

“Jimmy” “Major”

AS a figure in the military world, probably no other man in the class is so renowned as Jimmy. For who else can claim the honor of having attained the rank of Major? The name of Webb is written large in the history of the Washington High School Regrets. The Major has spent a large share of his time at the U.S.N.A. in living on his reputation; he has been known to bone occasionally, but only when on the lee side of a 2.5. Anything that may be proposed will find Jimmy ready for business, particularly if it sounds like a big liberty. He has qualified for a pink N, and is one of the most graceful athletes who appear at the hops in his opinion, a larger percentage of the young officers who have recently graduated should be sent out to China.

As a friend and good fellow, there is no one better than Jimmy; he adapts himself to any company, and the more you know of him the better you like him.

Clean Sleeve—Buzzard

I’ve been studying entries in the Lucky Bag for years and still have some trouble interpreting the lingo they used. Like all prospective sailors, they have a language unto their own. But based on looking at the men and their later accomplishments, it’s interesting how close their descriptions meet their outcomes.

First assignment: USS Arkansas

All graduates of the academy on those days would be assigned to one of the seagoing units for further seasoning. In Wenn’s case that included being assigned to the USS Arkansas in January 1914 and later to the USS Montana in January 1915 Ensign, torpedo instruction.

USS Arkansas, a 26,000-ton Wyoming class battleship, was built at Camden, New Jersey. Commissioned in September 1912, she spent her first seven years of service with the Atlantic Fleet. In 1913, Arkansas cruised in the Mediterranean, and in 1914 she participated in the U.S. intervention in Mexico.

USS Montana (ACR-13/CA-13), also referred to as “Armored Cruiser No. 13”. She was the last of the coal fired armored cruisers built and also participated in the Mexican intervention. Like other contemporary armored cruisers, she was also armed with four 21 inches (533 mm) torpedo tubes located below the waterline in her hull.

Submarine Duty

In January 1916, Ensign Webb would be assigned to the USS L-4. The L-4 would be assigned to the Atlantic Submarine Flotilla, L-4 operated along the Atlantic coast, assisting in the development of new techniques in undersea warfare until April 1917. The L-4 was laid down on 23 March 1914, launched on 3 April 1915 and commissioned on 4 May 1916. The Electric Boat submarines had a length of 168 feet 6 inches overall, a beam of 17 feet 5 inches and a mean draft of 13 feet 7 inches. They displaced 450 long tons (460 t) on the surface and 548 long tons (557 t) submerged. The L-class submarines had a crew of 28 officers and enlisted men. They had a diving depth of 200 feet.

Many lessons were learned with this pre-war submarine. This was the first U.S. submarine class equipped with a deck gun, in this case a 3-inch/23 caliber (76 mm) partially retractable design. The gun was installed on the EB design boats only, the Lake design never received one. The gun was retracted vertically, with a round shield that fit over the top of a well in the superstructure that projected into the pressure hull. Most of the barrel protruded from the deck, resembling a stanchion. The round shield doubled as a blast deflector for the gun crew, and as the watertight top of the well. This gun was roundly disliked by the submarine crews because it lacked range, hitting power, and had the tendency to retract back into the well when fired, presenting a great hazard to the gun crew.

PREPARING FOR WAR

In January 1917, Ensign Webb received his next assignment. As a submarine experience officer, how would have taken a hand at training his crew in the ways of operating in a hostile environment. The war in Europe had already been raging since 1914 and submarine warfare was having a significant impact on the opposing sides.

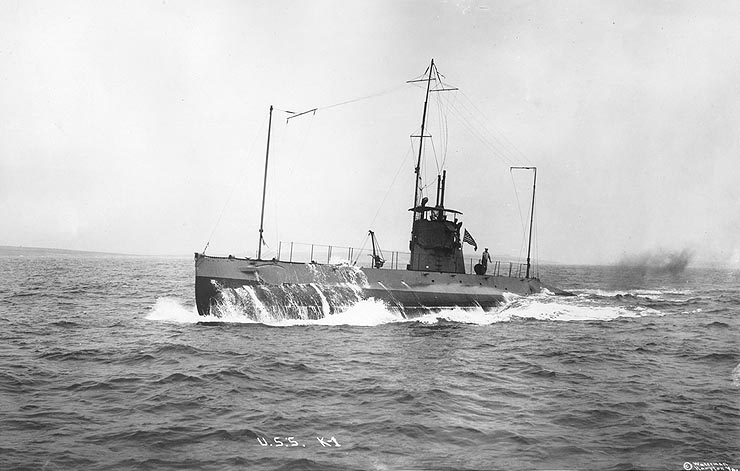

K-1 HISTORY

Upon completion of six months training, K-1 joined the 4th Division, Atlantic Torpedo Flotilla, Newport, Rhode Island, on 9 October 1914. The submarine departed New York City on 19 January for underwater development training out of Key West, Florida. She continued operations along the East Coast for almost three years, aiding in the development of submarine-warfare tactics. The techniques learned from these experiments were soon put into practice when U-boats began attacking Allied shipping bound for Europe.

K-1 departed New London, Connecticut, on 12 October 1917, arriving Ponta Delgada 15 days later to conduct patrol cruises off the Azores. For the duration of the war, she conducted patrol cruises off the Azores and searched for the enemy U-boats, and protected shipping from surface attack. Upon cessation of hostilities 11 November 1918, the submarine arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 13 December to resume coastal operations.

In March of 1918, Webb had been promoted to Lieutenant and became the commanding officer of the USS K-1, But something interesting in his career happened at that point.

BRINGING HOME THE PRIZES

At the completion of the war, the German Fleet was forced to surrender or scuttle their fleet. A particularly valued prize was a group of submarines that were handed over to the American navy from the British navy.

https://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08433.htm

To Be Displayed at American Ports in Connection With Victory Loan Campaign By Associated Press Washington, March US.

Five surrendered German submarines will leave England tomorrow for the United States manned by American crews and convoyed by the American submarine tender Bushnell They are expected to arrive in American waters late in April and will be displayed at ports to be selected in connection with the next Liberty Loan campaign. One of these craft Is the U-117. a sea- going mine layer, which during the war planted mines along the American coast. Two of them are the UB-88 and the UB-148, regular submersibles of the smaller type. Another is the UC-97, one of the small mine layers, and the fifth is the U-111, the standard German U-boat. Later it is expected that one of the big cruiser submarines, equipped with deck guns, will be sent over. Adverse winds at this time of season and unfamiliarity of the American crews with the machinery make the date of the arrival of the ships uncertain. Crews for the submarines were assembled in England, most of the men being sent from the United States. Naval orders, published today, showed the arrival at London of seven lieutenant commanders who were sent there in connection with German submersibles. They are H. C. Frazier. E. G. O’Keefe (U 148), J. L. Nielson, C. M. Lockwood (Commanding Officer UC 97), G Hullings (Navigator U111), G.B. Junkin and J. R. Webb.

(Others – Lieut. Vincent Astor U 117)

FOUR U – BOATS SAIL FOR THE US

Captured Craft to Be Used Here for Exhibition Purposes.

Harwich, England, March 31, Four German submarines, convoyed by the United States submarine tender Bushnell. left here for the United States. Many more than the required number of officers are making the trans-Atlantic trip on the captured craft.

After the initial reports of assignments, further word from Washington determined which officers would actually command the captured vessels.

Washington, March 31. Assignment of naval officers to command German submarines, which are coming to the United States for exhibition, was announced by the Navy Department today as follows: Lieut. Commander H. Gibson, UC-97 Lieut. Commander J. L. Nielson, UB-88: Lieut. Commander A. O. Dibrell, U 117; Lieut. Commander H. T. Smith. U148. (Missing is U 111 LCDR Daubin who ended up being Commanding Officer).

Reporters noted: “There is a typical submarine smell” Stories from the U 111 Archives

https://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08433.htm

The U boats accomplished the goal of raising money to retire the war debt. There is an interesting note about Lieutenant Commander Lockwood sailing his prize boat into the great lakes that cause an international incident. That is a story for another day but it was something that would be very front-page news today with the current US/Canada relationship.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE MODERN AMERICAN SUBMARINE

Up to this point, Webb has spent a significant portion of his career learning the craft of submarining. The boats were simple craft in comparison to the ones we have today. Basic engineering with engines and batteries that had the limitations imposed by the technology of the day. But the German submarines and American ingenuity were rapidly bringing the submarine force into a next generation status. Even though the boats remained cramped and with little habitability, their motive power was gradually increasing. Each improvement made them more capable for future conflicts.

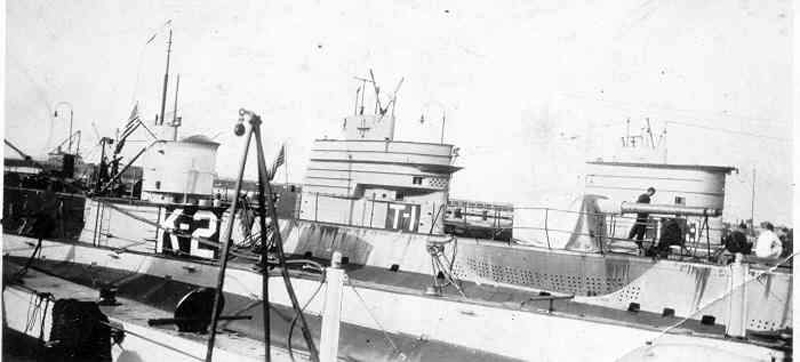

USS AA-1

After marrying Bessie Adelaide Masters on August 9, 1918, in Manhattan, Lieutenant Webb’s next assignment January 1919 would be to a boat called the USS AA-1. The first USS T-1 (SS-52/SF-1) later named USS Schley, was an AA-1-class submarine which entered after the first world war with the United States Navy. The AA-1 class which only comprised three experimental boats were designed and constructed under a project of the US Admiralty to develop fleet submarines, giving them sea-keeping qualities and endurance for long-range operations acting as submersible scouts for the surface fleet.

The T-1 class submarines (previously known AA-1 class) were the first attempt by the USN to build a fleet submersible. It was planned in 1913 already to operate with the new Delaware class, the first “standard battleships”, with a surface speed of 21 knots to act as scouts. It was a radical departure from conventional approaches that saw the submarine as a coastal defense asset with good underwater speed and agility. Only greenlighted in 1917 when construction commenced at Electric Boat in the Massachusetts, they had been designed in a rush, with an existing designed stretched to accommodate five massive New London Ship and Engine Company (NELSECO) diesels, two paired on each propeller, one used only to reload batteries.

When commissioned eventually after nearly six years of constructions they initially showed promised, being capable of reaching 20 knots on trials. However, they were plagued by huge structural issues and engine unreliability which shortened their service life down to just three years of service on average. They spent their time in the mothball fleet before being stricken in 1930 and sold for BU, the example of “how not to do it”. But each lesson learned made the fleet stronger.

ASSIGNMENT TO THE H-1

After only one year on the AA-1, Webb would be assigned as a Lieutenant Commander in January 1920 to the USS H-1.

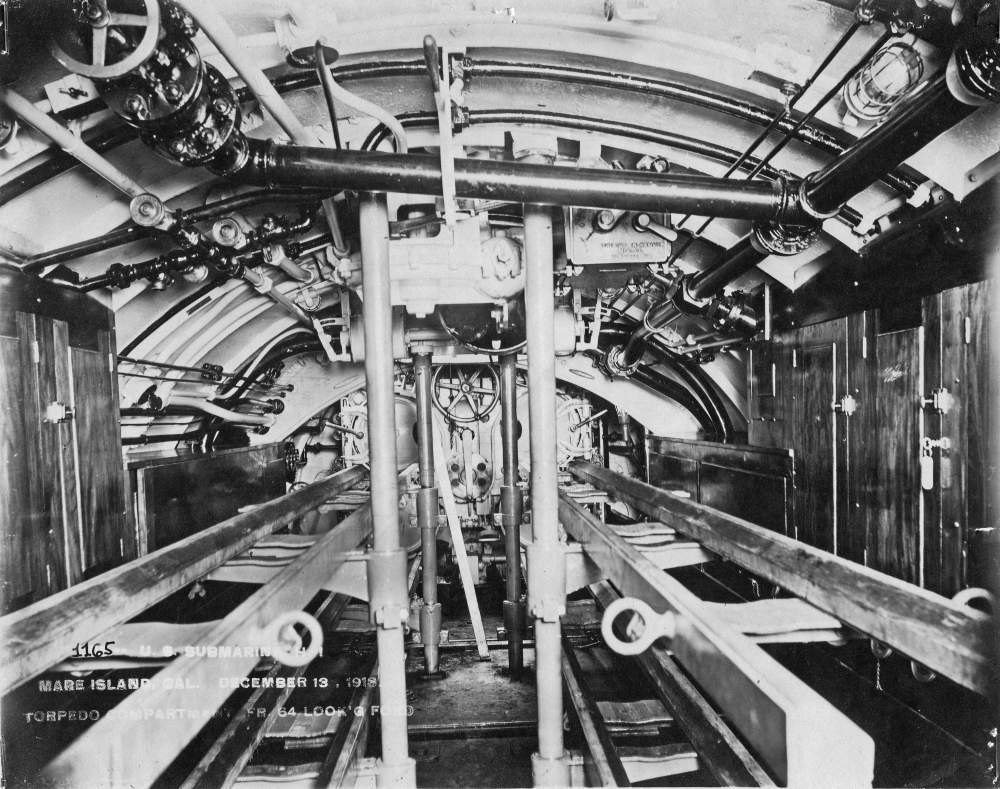

Originally named Seawolf — the first US Navy ship to be named after the formidably betoothed fish — the submarine was built by the Union Iron Works in San Francisco in 1911, the diesel engines by Electric Boat in New London, Connecticut. She was renamed the less exciting H-1 in November of that year and launched in 1913. H-1 was the lead ship of the H-class submarines and patrolled the West Coast until a few months after the United States entered World War I in April 1917. That October, she was deployed to New London and patrolled the Atlantic coast around Long Island Sound until the war’s end. She was ordered back to her home base in San Pedro, California, in January 1920.

https://kaxaan.org/living-museum-us-h1-seawolf-submarine/

The H-1 was bound from the Canal Zone to the Pacific submarine base at San Pedro and was on that leg of the journey lying between Balboa and La Union, Mexico. The fog that they encountered was heavier than anyone on board could remember. The problem with those early submarines was that they lacked sufficient surface radar to navigate well in these circumstances. The typica navigational tools would include visual sightings of landmarks, celestial navigation by the stars and accurate charts that depended on both. Webb’s skills certainly would have been among the best based on his years sailing on all of his previous boats. But on that night, they were not enough to overcome the shroud of fog that surrounded his group.

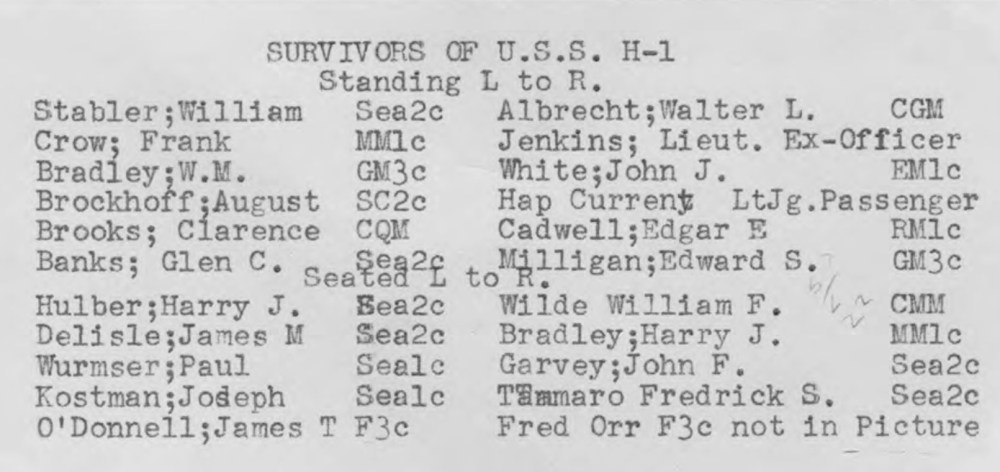

After crossing the Panama Canal, the H-1 went ran aground on a shoal off the coast of Santa Margarita Island in Mexico’s Baja California on March 12th, 1920. Efforts were made all night to try and free the boat from the rocks. Unfortunately, the shoal held tight and the actions that were taken to free her probably damaged the hull which more than likely produced flooding into the boat. The later investigations indicated that seawater entered in such a manner as to reach the battery. As any submarine knows, water and batteries do not mix will. The result would be toxic gasses released into the confined space of the submarine. That quickly makes breathing nearly impossible, and the decision was made by Webb to abandon ship.

They were unsuccessful and the decision was made to abandon ship. The ship was being battered by heavy surf and the captain (Webb) directed the evacuation of the men. Most were probably choking and partially blinded by the gasses. Since he was on the conning tower directing the evacuation, he would also have to have been affected. But he patiently directed his crew off until the end.

From the press: In the absence of authentic reports as to the manner in which the four naval men were killed, belief in naval circles here was that they either were asphyxiated by chlorine gas generated when water reached the submersible’s batteries or were carried overboard while attempting to escape the fumes after the H-l had beached. Wireless messages to Rear Admiral Roger Welles said chlorine gas was pouring from the conning tower of the craft last Saturday, twenty-four hours after she had beached, and that a heavy sea was running. The destroyers Sinclair. McCawley and Meade are standing by the H-l and the destroyer Woolsey and the fuel ship Neptune are enroute to the scene of the accident, which is about 650 miles south of San Diego.

From another news report: Lieut. Commander James R. Webb and three members of his crew were lost when the United States submarine H-l went aground at the entrance to Magdalena Bay, lower California, according to a radio dispatch received here. Besides Lieut. Commander Webb, those listed as dead were H. N. Gilles Machinist mate; M. H. Delarmarine and Joseph Kaufman, seamen. The bodies of two of the men were reported to have been buried by the survivors in the beach of Santa Margarita Island, in the mouth of Magdalena Bay, about 650 miles south of San Diego.

The body of Lieut. Commander Webb was never found. He was 30 years old at the time of his passing.

Final News Report

March 15, 1920

WEBB MISSING WHILE WIFE SPEEDS TO MEET HIM

Fear Commander of Stranded Submarine Dead.

Well Known in Capital

With his wife speeding across the continent to meet him upon his arrival at San Pedro, Cal. , Lieut. Commander James Ross Webb, well known Washington Naval Officer naval officer, in charge of the United States submarine H- 1 which grounded it the entrance to Magdalena Bay. Lower Cal.. Friday, today is reported missing with a member of his crew and believed to be dead.

Shortly after the line which the destroyer Sinclair succeeded in getting to the stranded underwater craft parted Saturday afternoon, it was discovered that Commander Webb and three members of his crew were unaccounted for. Two of the missing seamen were later found dead and the whereabouts of Commander Webb and the two others remains a mystery. The bodies of the dead members of the crew were buried on the beach of Santa Margarita Island in the mouth of Magdalena Bay

The H-1 was bound from the Canal Zone to the Pacific submarine base at San Pedro and was on that leg of the Journey lying between Balboa and La Union Mexico. Mexico, in anticipation of meeting her husband, Mrs. Webb, who lives with his parents at 1818 Monroe Street northwest, left Washington several days ago for San Pedro. Whether or not she knows of the uncertain fate of Commander Webb is conjecture.

The H-l went aground Friday and in answer to an S. O. S., call sent broadcast soon after the accident by the U. S. S. Eagle and several other naval and revenue boats in the vicinity rushed to the submarines aid. The destroyer Sinclair, after much pitching about in the high seas, succeeded in getting a line to the H-l Friday night, but it broke the following day, leaving the vessel to the mercy of the waves.

Commander Webb in well known In Washington, where he has spent most of his life. He was born In Seneca, SC thirty years ago and came here shortly thereafter with his parents. His father. James M. Webb, Is the freight claim agent for the Southern Railroad.

Epitaph

James Webb was a part of the American Submarine Story. While we may never know how much more he may have added to our tapestry, this much can be assumed. He was at the very heart a submariner. He rode boats that were a mix of strength and fragility. The strength was the hearts of the men who sailed them despite the odds. The fragility was that they were cramped, foul smelling, dangerous in too many ways, surrounded by a sea that could kill in an instant and facing enemies that were known and unknown. They were heroes. Despite all of the odds, they climbed down narrow ladders into spaces barely lit with incandescent lights. The sailed into cold seas and slept on the smallest cotton padded bunks possible with little sleep and unlimited stress.

From the captain to the seaman on each boat, they shared the reality of food that was too sparse, coffee tainted with the smell of the fuel that propelled the boat on the surface, and a complete lack of privacy in even the most intimate parts of our daily functions. The odor in those early boats that lacked even the most basic ventilation purification was so remarkable that most land lubbers could last but a few moments when allowed access in port.

Webb’s contemporaries would ride on to great heights. Men like Nimitz and Lockwood would later lead large numbers of fleet boat sailors to victory over an enemy that had also learned submarine warfare. It wasn’t just our superior technology that eventually won the day. It was the one weapon that was perfected by the service and sacrifice of men like Webb. With each generation, the obstacles would be overcome by technological innovations. But no one should doubt that without the sacrifices of that early generation, American submarines would not have advanced as far as they have today.

If you want a real bigger than life American Hero, I present you James R. Webb, United States Navy Submariner.

Mister Mac