After World War 2, the US Navy had a surplus of many items from the big war. On both the east coast and the west coast, temporary resting places for many of the ships and submarines were teeming with no longer needed ships and submarines. I remember seeing large numbers of ships tied up and mothballed out in California when I was stationed at Mare Island. One surplus they did not have was trained sailors. By 1950, that was becoming a problem.

But by early 1950s, the Cold War was already starting to overheat in far flung corners of the world. The need for trained sailors of every type was still evident as we found ourselves drawn into the conflict in Korea and other smaller areas. The Soviets were developing their own blue water navy and that included submarines. The answer was to continue to improve the existing US fleet and find enough people to man it.

Submarines had always been a voluntary service.

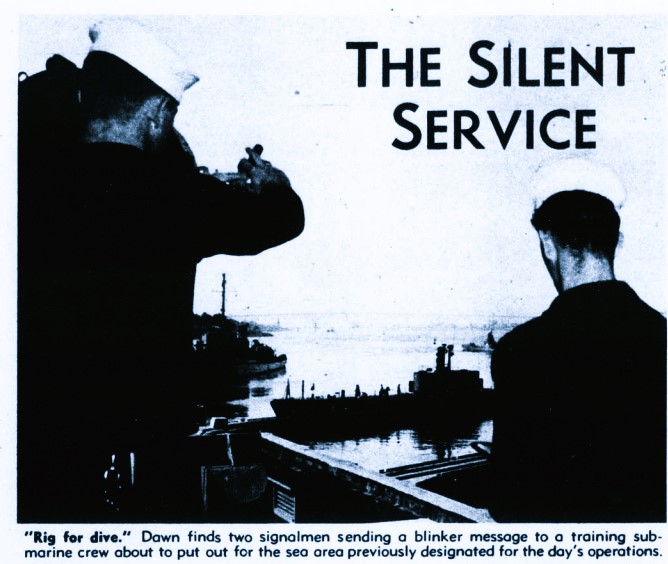

The balance between keeping the operations of submarines secluded from the public eye almost always had to be balanced with giving the public enough information to attract the men who would be needed to operate them in future conflicts. Submarining is adventurous at best and downright dangerous at worst. The loss of 52 boats in the second world war (not counting the large number of foreign boats sunk) could be a discouraging factor.

So public pieces on submarine duty and training added a sense of uncloaked mystique to the readers of contemporaneous periodicals. The navy in 1951 was very interested in getting articles published which could entice potential submariners to come forward.

From the Library of Congress Archives, two such articles really stood out as examples.

Washington Evening Star, September 23, 1951

THE SILENT SERVICE

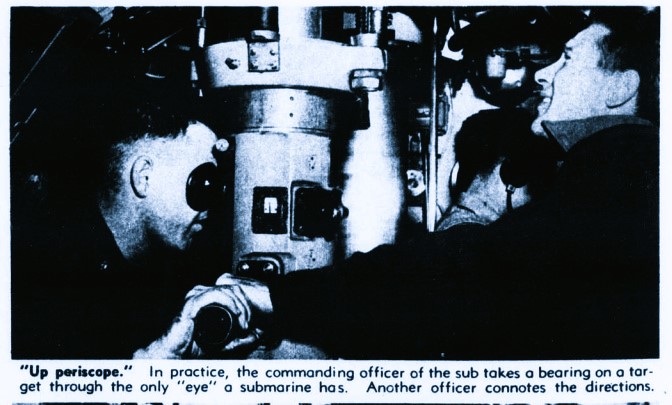

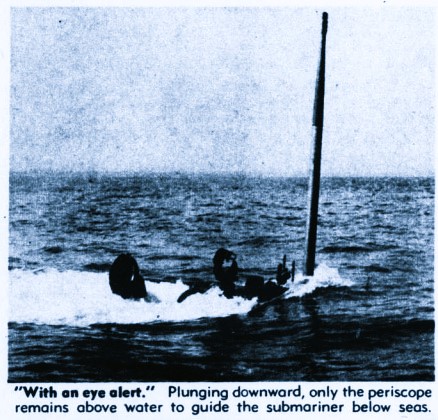

The modern submarine is a deadly, ingenious and effective ship of war. Per square inch, there is more science packed into it than into any other warcraft. Recognized as a legitimate war instrument since the Civil War, it has been used for many and varied missions. Aside from primary combat duties, the submarine can perform supplementary missions of rescue, scout, coastal raider, troop transport, supply ship, mine layer, emergency evacuation ship and advance fueling base for long-range planes.

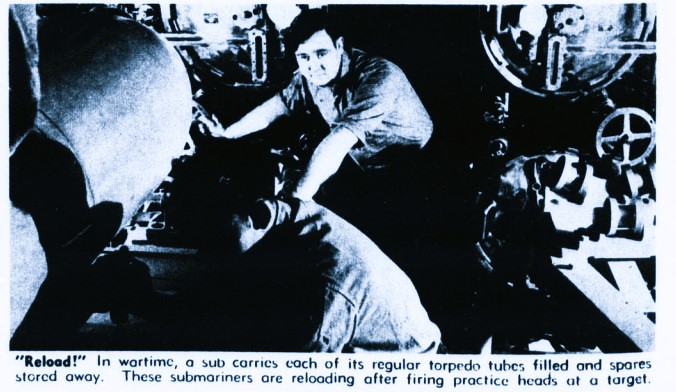

The torpedo, its major weapon. can be discharged from any of the boat’s 10 tubes, and a single hit could cripple or sink the mightiest warcraft afloat.

During World War II. submarines of the United States Navy destroyed 214 Japanese naval vessels and 1,178 merchant vessels of 500 or more gross tons.

Comprising less than 2 per cent of the Navy s total personnel during World War II, submariners accounted for two thirds of all enemy ship losses.

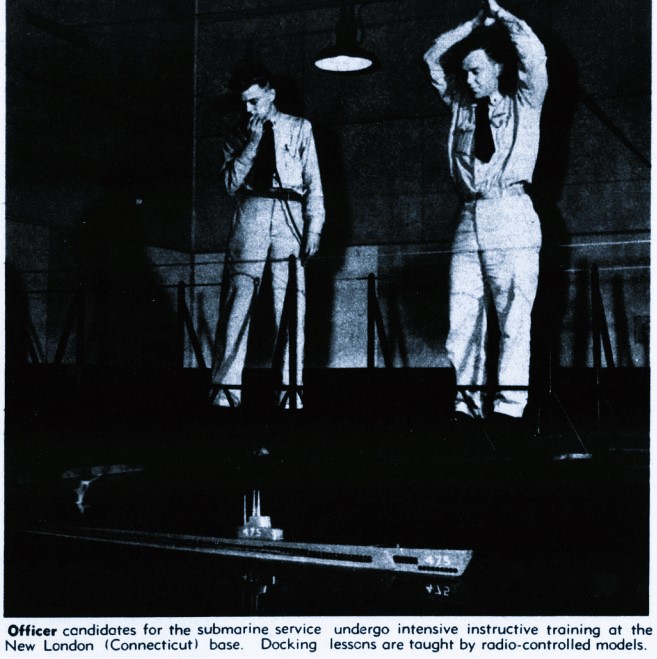

Back of this record is the story of training at the submarine base on the Thames River near New London. Conn. Practically all the officers and men who wear the “Twin Dolphin” insigne of the qualified submariner receive their initial training at this school. All volunteer for this duty and few have any desire for a change after earning their “dolphins.”

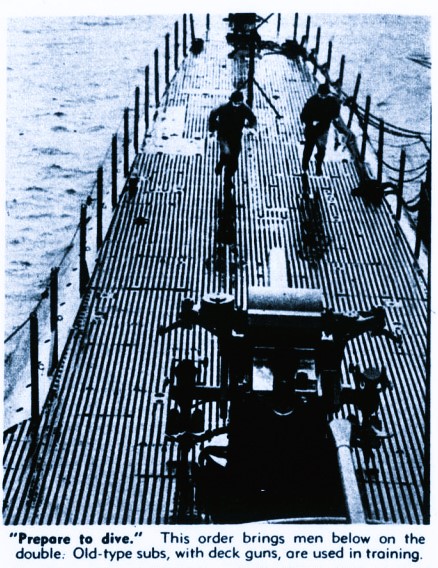

A submarine is an intricate piece of machinery built with the precision of the watchmaker’s art. Consequently, the would-be submariner must be an emotionally mature individual who can exercise good judgment, keep his head in emergencies, be reliable in the performance of his duties, and accept the confinement of submarine life without becoming a liability to the rest of the men.

After qualifying, enlisted personnel receive eight weeks of basic training in appropriate subjects. Instruction in classrooms and training devices, coupled with stints aboard a “live” sub form a sound foundation in undersea warfare fundamentals.

An enlisted man who graduates from school and reports to his first “pig-boat” is not a finished submarine sailor. There is a great deal for him to learn about his special rating, as well as the detailed workings of the submarine itself.

After six months aboard, he rates an entry in his service record which states that he is “Qualified in Submarines.” With the building of newer and more complex vessels, the submarine will become an even more formidable weapon. By nature of its operations, the submarine service is shrouded in secrecy. As a result, it has long been known as “The Silent Service.”

Well, by 1955 they were making progress. But the men coming in still needed special training.

November 27, 1955

UP FROM THE DEPTHS

How a Man Is Taught to Make Like a Fish

By MEREDITH S. BUEL

SUBMARINE BASE, NEW LONDON. CONN.

PAT CRONANT’S mouth was dry, and his hands fidgeted with the sailor knot in his tie. He stopped before entering the silo-shaped building, glancing skyward. This was no ordinary silo. It was filled with water. In a few minutes, he would be in it and under it.

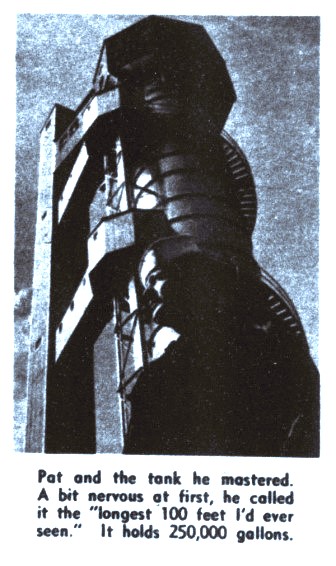

Up through 100 feet of water to the top was to be his goal. Squinting as the bright autumn sun bounced off the circular steel structure, Pat thought:

That’s the longest 100 feet I’ve ever seen!

He was about to be tested here in the Submarine School’s escape training tank, a unique underwater classroom.

Students ascend with the Momsen lung, an easily stowed, bag-like breathing apparatus, from 18, 50 and 100-foot depths, simulating returning to the surface through the fore and aft escape hatches of a sunken submarine.

Pat, 24, is a hospital corpsman second class. They call him “Doc.” Seven years in the Navy, he entered the Submarine Service last August. He had told his wife, the former Marilyn Betxler of Washington:

“Not only will I get more money on submarines, but I’ll be the only medical man on board.”

Pat liked that kind of responsibility. And the school was offering him advanced medical training to fit him for the Job. He was apprehensive, though, when he had to tell his wife about the escape tank—with its changing pressures, its tests of a man’s physical and mental reactions—and his courage.

To qualify in this service, tank day was D Day—DO it or else. For men of the Silent Service must be like offspring of the silent world they travel, to be spawned from the great steel fish if the day ever comes when the sea tries to claim them. To Pat’s relief, his wife promised not to worry. After all, she reasoned, he once had been on a Navy swimming team and was at home in the water.

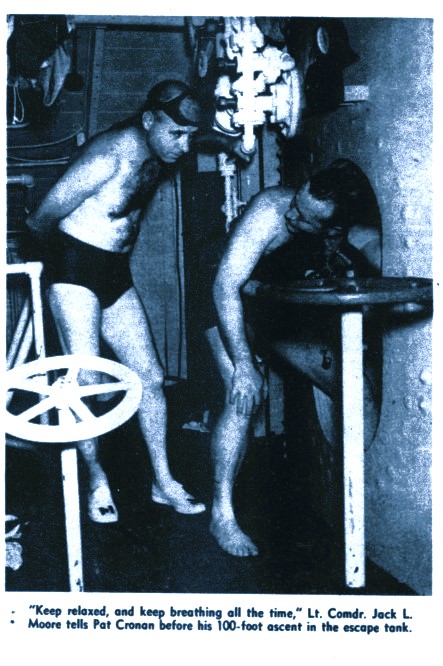

But on D Day, Pat felt nervous. He thought of Marilyn’s confidence, of their three kids, Tommie, 3; Dawn, 2, and Terry Ann, 4 months, and their Cape Cod house at 2408 Arlington boulevard, Arlington, Va. Sure he was uneasy—that was only human—Lt. Comdr. Jack L. Moore, training tank director, had told him so.

“We’re land animals—not fish,” he had said, “so the thought of breathing underwater is unnatural to us.” Comdr. Moore had mentioned this when Pat and 14 other students had crowded into the tank’s recompression chamber. “All right men, we’re going down more than 100 feet and back to the surface,” said Comdr. Moore after the hatch door was dogged.

“When the air pressure starts, hold your nose and blow. This will equalize the pressure in your ears. Keep a little ahead of the pressure and you’ll have no trouble. If you can’t clear your ears, raise your hand.”

(The men already had passed swim tests and rigid medical examinations.)

Outside, Instructors began to turn a series of large valves. Pat cleared his ears easily as the pressure mounted. One sailor raised his hand. Pat knew what that meant. When you can’t clear your ears, because, say. of a cold or a sinus infection, it was like having your head pressed in a vice, he had heard. But the man was in no danger of a broken ear drum or other complications, as Comdr. Moore quickly took him to an ante chamber, sealed it off by closing another hatch door and brought him back to the “surface.”

Pat and the others perspired through the experience in fine form. He was relieved to know he could stand high pressures without ill effect.

And now the afternoon of the same day, when he walked in for his underwater tests, Comdr. Moore had said: “Relax, Doc. If you can take that recompression chamber, you won’t have any trouble in the tank.’’

But still, Pat thought. I’m a land animal. . . .

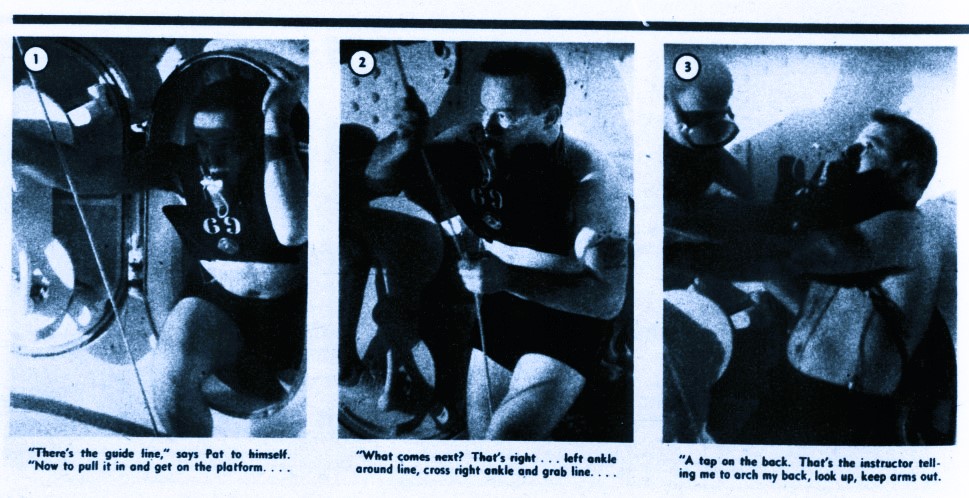

Pat put on bathing trunks in the locker room. William (Jake) Jacobsen, engineman first class, in an Intensive half hour of Instruction, explained to him every phase of assent, ranging from the workings of the Momsen lung to a series of underwater signals instructors would use to help him.

Jake’s final words came as a warning:

“Be sure you breathe in and out regularly as you ascend the guideline If you hold your breath while ascending, your lungs will swell like a balloon and burst. But don’t worry. Well make you breathe!”

The elevator door opened and closed behind Pat. Before he could catch his breath, he was at the top, facing a cylinder-shaped pool, its green water spilling over the toes of instructors surrounding it. Even Lt. John H. Schulte, submarine medical officer, was standing by in case of emergency.

Pat looked over the side. So clear was the view that he could see to the bottom—.to the 100-foot level escape hatch, toward which a searchlight pointed a thin, trembling white finger.

“You won’t find your drinking water as clear as this,” Comdr. Moore said. “While instructing you from the surface, I can see every move you make through a glass-bottomed steel box.”

Pat smiled when he saw two shapely mermaids painted on the tank wall 15 feet down. One redhead even out- curved Marilyn Monroe—and the wiggle was there, due to the rippling water. He relaxed a little.

First, he got acquainted with the lung. It was charged with an air hose. He backed down a pool ladder, ducked and took his first underwater breath! No water seeped into his throat through the mouthpiece and a nose clip prevented It from going into his head. He ducked under several times. So far, so good.

“All right Doc, you’re ready for the 18-foot ascent,” Comdr. Moore said.

Now came the first big test. He and Jake went down in the elevator to the 18-foot level. They entered the escape hatch, about the size of a hall closet. The hatch door behind him clanged shut.

“Lucky I don’t suffer from claustrophobia,” Pat thought.

The elevator, his initial ducking and breathing underwater and now the airtight hatch, all contributed to that closed-in feeling.

Air hissed into the room. Jake turned a water valve, and the compartment began flooding.

This is almost like being in a bathtub, Pat thought as the water tumbled in over his legs. (Tank water is kept at 92 degrees, as instructors are in it continually.)

The warm stuff crept up to his chest and stopped. Why?

“The weight of the air compressed to the top of the hatch keeps the water from rising any farther,” Jake told him.

Pat cleared his ears as the pressure increased. When the inside pressure equaled the outside water pressure at 18 feet, the hatch door leading into the tank opened a crack. Jake pushed it wide.

Again, Pat’s lung was charged with an air hose. The trainee put on his nose clip, inserted his mouthpiece and ducked underwater to check his equipment. Then he leaned out of the hatch. With a sweep of his right arm, he caught the dangling guideline (fastened to a surface buoy), as Jake bad instructed. He placed bis left band above his right on the line and stepped to a platform outside. His left ankle went around the line, and he crossed his right ankle over. Now he had the line firmly. He looked down briefly and, through blurred vision, saw the 100-foot marker, 82 feet below.

“Doc, you’re on stage,” a voice boomed next to him. “Don’t worry If you’ve forgotten some instructions. I’m right there with you.”

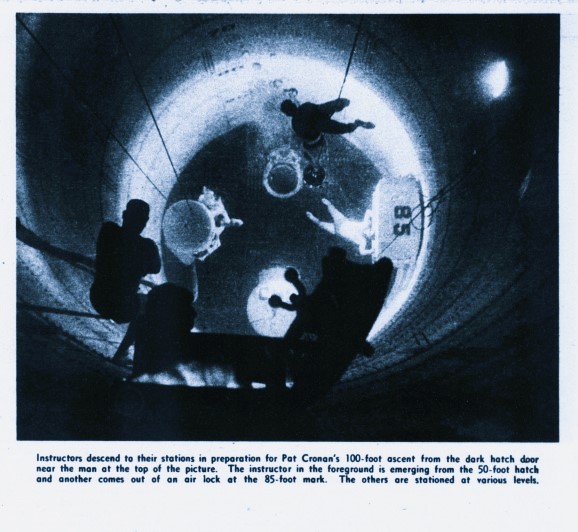

Comdr. Moore was watching from the surface. Pat was hearing his voice via an underwater public address system. From the surface an instructor had dived down and Joined Pat as he left the hatch. A diving bell with two instructors also was alongside him.

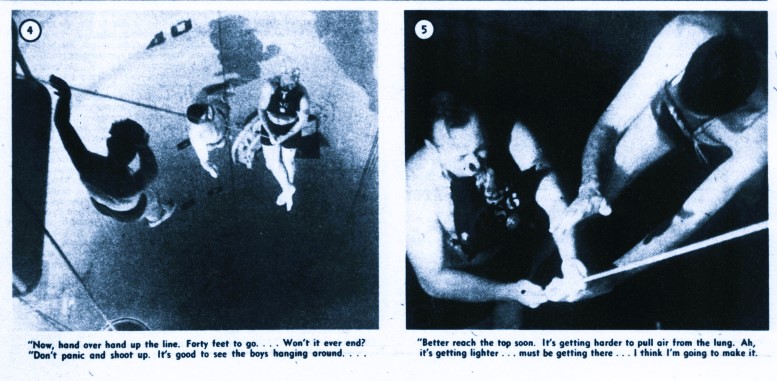

He arched his back, looked to the surface and started up the line, hand over hand. “Relax and breathe deeply,” came the words from above. “Breathe, boy! Let me see those air bubbles!”

Pat sucked In and out with renewed vigor. He held the lubber flange firmly between his teeth, and his lips were well over the mouthpiece, making breathing easy. He didn’t worry about losing his grip and plummeting to the bottom. Actually, his own buoyant body and the air-filled lung tried to force him up too quickly. In 35 seconds, he surfaced.

What a relief to be up and breathing fresh air! he thought.

What a relief to be up and breathing fresh air! he thought.

“You’re a little too still, Doc—try to relax more on the next run,” Comdr. Moore counseled. Again, he made the 18-foot ascent, gaining confidence. Although the 50-foot pull to the surface seemed to him “like an eternity,” be began to feel more at home with the mermaids and his silent surroundings. And, indeed, he began to feel a close kinship to the line that bore him up and to the instructors hovering around him underwater like seals protecting their young.

Twice the 50 would be his final goal. But because of the ill effects pressures and gases have on a human body continually in deep water, Pat learned he was to put off the 100-foot ascent. He was to spend the next day on his first training cruise in a killer-type submarine. So, he was to report to the tank the morning after.

He was there at 8 am. He had slept hard after making 12 dives on a sub.

“You’ll make one 50-foot ascent as a warmup for the 100-foot test,’ Comdr. Moore told him.

Pat had skipped breakfast, and the trial run was exhilarating. It woke him up, sharpened his reflexes and eliminated some of that butterfly feeling in his stomach. Pat and Jake started down the elevator; this time accompanied by Cmdr. Moore. Now the big moment was at hand.

Won’t this elevator ever get to the bottom? Pat thought anxiously. He remembered his impression of the tank outside—how I—o—n—g it seemed to the top. The only human “fish” he’d ever heard of being 10G feet deep were those heroes of adventure magazines.

The elevator bumped to a stop. Comdr. Moore led the way to the hatch. “You’re now standing under 100 feet of water.” the tank director said. The hatch door was dogged. Pat cleared his ears again and again as pressure mounted. Water rose around him. TO him, it took forever (a minute and 40 seconds) for the hatch door to crack open.

(This chamber is large enough to hold 25 men. It is like the after-torpedo room escape hatch with an adjoining culvert-like passageway to climb up to the “out” door, after the chamber is flooded.)

“The 100-foot will seem the same to you as the 18 and 50-foot ascents—- except this one will take longer,” Comdr. Moore explained. His parting words were:

“Remember, we’re with you all the way.”

The next moment he was up the passageway, out the door and to the surface in 80 seconds, making a free ascent, without a Momsen lung, exhaling all the way.

“This is like climbing up a water- filled chimney,” Pat thought, as he went up the 10 rungs on the passageway ladder to the open door.

He took his position on the guideline. He looked through the 250,000 gallons of green. The line seemed to rise endlessly, like steps rising through the clouds to heaven in the movies he’d seen. The only sounds were escaping air bubbles.

Hand over hand he went …up, up, up. “Keep your back arched and look up,” came the voice of Comdr. Moore.

“Don’t hunch forward on that lung or you’ll deflate it. You still have 50 feet to go.”

The diving bell was beside Pat. Instructors flitted around him. They didn’t have breathing units, like moray eels whipping in and out coral crevices, they flashed In and out of compressed air locks, built in the tank walls at various levels affording them a breath of air. One instructor tapped Pat’s Momsen lung. This was the signal to breathe more deeply. Then a big air bubble rose from the lung’s exhaust valve. Another tapped his ankle as the rope nearly slipped from him.

“Lose a line in heavy ocean current and you may be swept away and lost,” the words of his early instruction began flooding his mind.

Lighter and lighter the water became, the surface light seeming to cast a giant sunbeam to reach up for. His eyes grew wide 10 feet from the top. And, as in football, the last few yards to pay dirt were the hardest He had to tug to get air from the near-depleted lung.

Then with a splash, his head sur- faced. The underwater battle had been won.

“That was the longest 90 seconds I have ever known,” Pat said, after learning It had Uken him that long from hatch to surface. “Yet It was probably the greatest thrill of my life when I neared the top and knew I was going to make It!”

Altogether, 12 Instructors plus Comdr. Moore and Dr. Schulte (all of whom are qualified deep sea divers) had taken part in Pat’s final ascent. He joined the ranks of some 160,000 other trainees who, in the last 20 yean, have triumphed on D day with the Momsen lung—without one fatality in that period.

And there’s been only one case, Comdr. Moore recalls with a grin, that it suddenly dawned on a sailor he was In the sub-surface fleet. “I had Just filled the recompression chamber with students when one of them bolted by me out the door,” he recounts.

“I called out, ‘Hey, son, where’re you going?’ “‘Home,’ was the reply. ‘My mother didn’t want me to be In the Submarine service nohow!”’

I will forever remember my one ascent in the tower. We used the Steinke Hood as our principal method, and we had to shout “Ho Ho Ho” at the top of our lungs all the way to the top. I understand there is a new tower in use now. The old one finally burned down.

The truth is that most of the operations we did would have made escape nearly impossible. I do not remember ever practicing the skill on any of my five boats. But at least it made my mom feel a little better knowing that there was at least a chance for escape. That was probably the whole point.