USS Pittsburgh and the First Pandemic

Over a hundred years ago, the world experienced a devastating pandemic called the Spanish Flu.

It traveled the world with incredible ease killing untold millions of people. The US Navy was not exempt in this tragedy. In 1918, the country was at war and heavily reliant on the Navy for defense and transporting soldiers and materials to Europe. Those ships were very much a part of the spread and frankly placed the sailors at extreme risk since the ships forced men to be in close quarters.

During World War I, 431 U.S. Navy personnel were killed as a result of enemy action and 819 were wounded. However, 5,027 died as a result of the Spanish influenza epidemic between the fall of 1918 and spring of 1919, more deaths than at Pearl Harbor, Guadalcanal, or Okinawa.

This story is about the armored cruiser USS Pittsburgh and the sailors on board who lost their lives to the pandemic.

From Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh

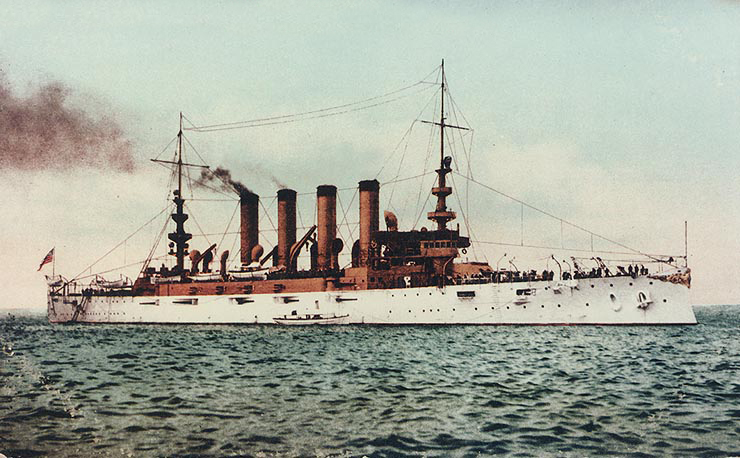

The cruiser USS Pittsburgh was originally named USS Pennsylvania. While in reserve at Puget Sound between 1 July 1911 and 30 May 1913, the cruiser primarily trained naval militia. She was renamed Pittsburgh on 27 August 1912 to free the name Pennsylvania for a new battleship. Before the transition, the Pennsylvania gained famed from its involvement with early attempts at flight from a ship. But as the USS Pittsburgh, Ishe would continue to provide years of service.

USS Pittsburgh patrolled the west coast of Mexico during the troubled times of insurrection which led to American involvement with the Verz Cruz landing in April 1914. Later, as a symbol of American might and concern, she served as flagship for Adm. William B. Caperton, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, during South American patrols and visits during World War I.

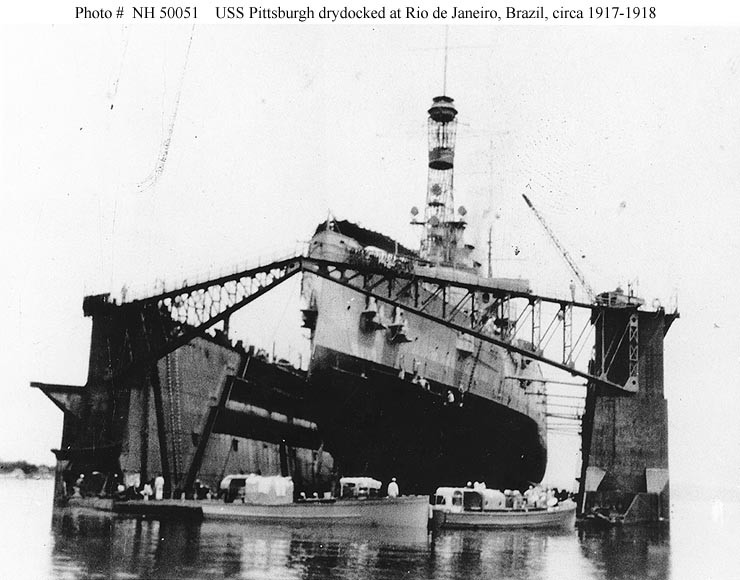

Cooperating with the British Royal Navy, she scouted for German raiders in the south Atlantic and eastern Pacific. While at Rio de Janeiro in October and November 1918, failure to implement quarantine procedures by Capt. George Bradshaw led to the spread of the deadly strain of Spanish influenza on ship, sickening 663 sailors (80% of the crew) and killing 58 of them.

From the Navy Historical Site:

The worst outbreak of all U.S. Navy ships occurred aboard the armored cruiser USS Pittsburgh (ACR-4) while in port in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Pittsburgh had formerly been named Pennsylvania—when she served as the platform for Eugene Ely’s first shipboard landing by an aircraft in 1911. By 1918, Pittsburgh was the flagship for the U.S. South Atlantic Squadron, guarding against German surface raider activity, under the command of Rear Admiral William B. Caperton.

The skipper of Pittsburgh was Captain George “Blackjack” Bradshaw. The crew of Pittsburgh referred to the ship as “USS Madhouse” and “Blackjack Bradshaw’s floating squirrel cage,” perhaps suggesting not the best of command climates to begin with. Rear Admiral Caperton‘s opinion of the captain was questionable. Not related to influenza, but in January 1918, a sailor aboard Pittsburgh had been murdered (somewhat bizarrely as a result of trading sex for candy) and five men accused of his murder and several witnesses had been transferred to the collier USS Cyclops to be taken to the United States for trial. They were aboard when the Cyclops disappeared without a trace in March 1918—leading to one unlikely theory to explain her disappearance.

The flu reached Rio on 17 September aboard a merchant ship from Africa, which was not quarantined, and within a month 30,000 people in the city would be dead. Initially the flu seemed to be of the benign variety and Captain Bradshaw permitted working parties to go ashore and continued normal liberty, although it was apparent by 4 October that the lethal strain was in the city.

The first case aboard the ship occurred 7 October and by the 11th there were 418 cases.

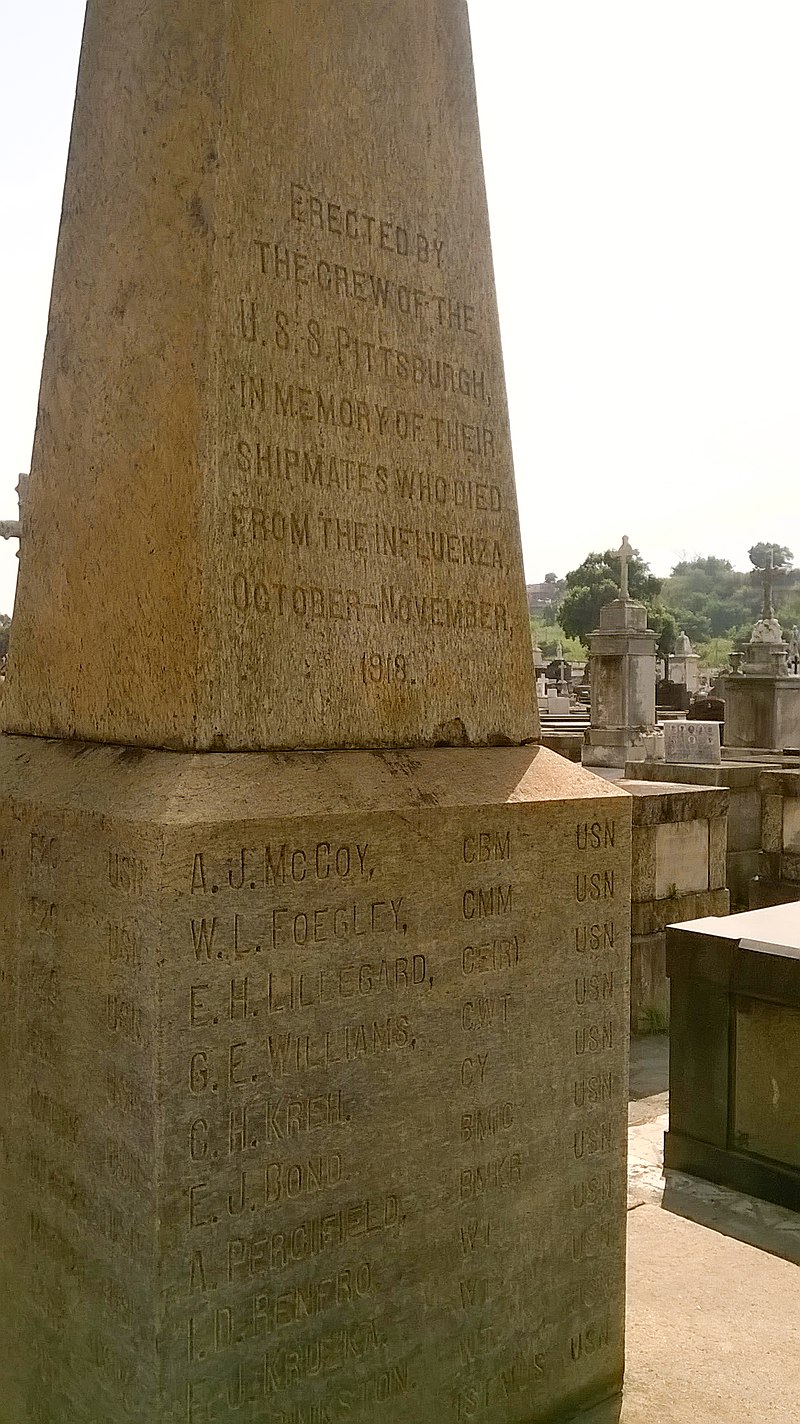

The first death, Seaman E.L. Williams, occurred on 13 October. Within a short time, 663 of Pittsburgh’s crew would come down with the flu and 58 would die. Rear Admiral Caperton’s account makes for particularly gruesome reading, as the extent of the illness quickly outstripped the ability of the ship to care for them or to deal with the bodies. Eventually, 41 of the crew would be buried ashore. Caperton’s account stated, “The conditions in the cemetery beggared description. Eight hundred bodies in all states of decomposition, and lying about in the cemetery, were awaiting burial. Thousands of buzzards swarmed overhead.” In other passages he describes the dead lying in the streets of the city untended, and bodies stacked like cordwood. Not surprisingly, the Pittsburgh was not capable of getting underway or performing any missions for over a month. Replacements were sent, and Pittsburgh did not return to the United States until March 1919. The bodies were eventually repatriated to the United States on the light cruiser Richmond (CL-9). A monument erected in their honor in the cemetery in 1920 is still there.

Personal account by Rear Admiral William B. Caperton of the 1918 Influenza on Armored Cruiser No. 4, USS Pittsburgh, at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

And then there came upon us the most terrifying of experiences. On the fourth of October we had noted that the so called Spanish influenza, which had passed thru Europe had made its appearance in Brazil. Bahia and Pernambuco were then suffering lightly. On the arrival in Rio of the SS Dannemara from Lisbon and Dakar, Africa, the ship reported four deaths from the disease during the trip, and the existence of several new cases when she came into port. The local health authorities, notwithstanding these, made no effort to quarantine the vessel or her passengers. The result was not unexpected to us. When the HMS New Castle arrived in Rio from Bahia on the 6th, she had sixty cases on board, all of a benign type. By the seventh the Pittsburgh reported a few cases and the disease was incapacitating hundreds daily in Rio de Janeiro, while the Lage Brothers shipyard was almost shut down. The following day 33 cases in the flagship, with the numbers ashore increasing alarmingly. By the 9th, 92 cases had made their appearance on board and hundreds ashore were dying without medical attendance. Hospitals were crowded and coffins almost ceased to exist. In the early hours of the 10th, in accordance with the previous arrangements, and in view of the probability of the Pittsburgh going out upon the high sea patrol for an extended time, she entered the floating dry dock. With my staff that morning I attended memorial services ashore in the Candelaria church for the repose of the souls of over more than a hundred Brazilian sailors who had died of influenza in their squadron abroad.

During the day, while the crew was working feverishly upon the sides of the flagship in the dock, the Department advised me that the Brazilian Ambassador to the United States, Da Gama, was to be returned to his native land by battleship and that I was to have the Pittsburgh proceed to the West Indies and transfer the ambassador to her.

By the next day, the 11th, there were 418 cases of influenza in the flagship, so that her activities for any duty were becoming handicapped. The seriousness of the situation was cabled to the Department with the suggestion that the ship bringing the Ambassador continue on its way and remain for the 15th of November, for which Brazilian National Day ships from Uruguay, Argentina and Chile would be there. That would make it incumbent that our representation be adequate for the occasion. On the 14th of October 644 cases had been admitted to the sick list, with about 350 more light ones not listed. One man died the day before. On the 15th three had died, the Commanding Officer, his heads of department and two members of my staff were sick, while the disease raged unabated in Rio where conditions defied description.

The Department, unaware of the seriousness and the rapidity with which the epidemic was spreading, directed me to have the Pittsburgh proceed to Bahia, as previously directed and there report her condition. Then, if unable to carry out the Department’s order, the Pueblo [Armored Cruiser No.7 USS Colorado] would be ordered to Rio with Da Gama. But the proscribed cruise for the Pittsburgh was an impossibility. Of that I informed the Department, adding that I was holding her at Rio. Conditions in the ship were rapidly becoming worse. More than half of the hospital corps were ill, and help was commandeered from all ratings and from the junior officers of the line. And the drizzle and the rain which had set in during the early days of the epidemic continued fitfully, rendering it difficult to find room for the cots of the sick who had been kept on deck in the open, during the good weather. Ashore people died like flies, and many lay in the streets for two or three days waiting interment, even a hole in the corner of a trench. By the 18th, twelve of the 48 pneumonia cases had died in the Pittsburgh. Further caskets could not be obtained ashore, at any price, and the burial of our men became an urgent necessity.

Six more men died on the 20th, when the Brazilian Minister of Marine offered us fifty cots in one of their Army hospitals. Accompanied by the Fleet Surgeon and Flag Secretary, my only able bodied aids, we visited the hospital, decided to accept the courteous offer, and rushed down to the house of the Minister of Marine to advise him of our acceptance. He came down to the door of his house, still clad in his pajamas. This good natured and kindhearted Admiral Alexandrino de Alencar, with a flourish of his hands and a few vivid words in French, announced his pleasure at our decision. On the 21st of October 16 bodies were taken from the Pittsburgh and landed for burial in the Sao Francisco Xavier Cemetery. Notwithstanding the previous arrangement with cemetery authorities for the opening of 20 graves, the funeral cortege arrived at the cemetery and found no graves prepared.

Those destined for us had been used by others. Much haggling with the cemetery authorities resulted, until finally the army officer in charge of the prisoners detailed eight to dig the graves required by us. These men were of practically no assistance to us and we were finally compelled to dig the graves for our own dead shipmates. Conditions in the cemetery beggared description. Eight hundred bodies in all states of decomposition, and lying about in the cemetery, were awaiting burial. Thousands of buzzards swarmed overhead. In the city itself there were no longer medicines, or wood for coffins and very little food. Rich and poor alike were stricken. In the big public hospital which had the contract for burying the city’s dead, hundreds of naked bodies lay thrown upon each other like cord wood and at least one instance was known of a live man being dragged out from the piles. The following day, thanks to the generosity of Mr. F.A. Huntress, the American manager of Rio Light and Power Company, arrangements were made for the proper transportation of those whom it was necessary to inter ashore.

My old Chinese cook, scenting the approach of death, went to the flag office and made out a will, leaving all his money and possessions to Uncle Sam, for as he said, the government had been good to him, and he had no relatives. Fortunately for us he survived.

Five more sailors were buried on the 23rd. During the afternoon forty patients were transferred to the Army Central Hospital by means of large streetcars, and the Fleet surgeon, Medical Inspector Karl Ohnesorg, tho ill himself, assumed charge there. The ship had been unable to secure milk or fresh eggs and no chickens could be obtained in the market at any price; while the contractors were hard put up to keep their contracts for the deliveries of fresh vegetables. The American women of Rio de Janeiro immediately offered their assistance and soon an adequate supply of fresh milk, eggs and chickens was available for the sick at the hospital, while sweaters and pajamas were sent off to the ship for the hundreds still in the throes of the disease.

By the 24th, 654 men were on the list with influenza and 46 of the 102 pneumonia cases had died. Two members of my staff, seriously ill, were transferred to the Stranger’s (British) Hospital in the city. The army authorized and then gave us one hundred beds in the hospital and the Pittsburgh transferred cooks and sufficient hospital corpsmen to care for the contingent ashore. The Rio Light and Power Company generously loaned us all manner of kitchen ware, glassware, ranges, mosquito netting, bed screens and other necessities for use in the hospital. The last days of the month found considerable improvement in the flagship. By the 31st of October there had been 58 fatal cases, but great improvement was shown throughout the ship and many men were returned to duty. Ashore, more than one thousand people died daily. Many of those whom we had known well and been fond of were carried off and the streets of Rio de Janeiro, generally gay and vivid with movement and color, were deserted and motionless. Here and there an occasional automobile was the only sign of life, while now and then some poor native with a miniature coffin on his head and followed by a sorrowful family trudged drearily to the nearest cemetery with his loved load. No description of the sorrows and troubles which attended us would be complete without suitable reference to the Brazilian officials, from the President of the Republic, his Secretary, the Ministers of War, Marine and of the Interior down to the lowliest of sailors, who did so much and spent so much of their time that every solace be offered our men and all possible assistance rendered to them. More nearly did they take to heart our sorrow than they did their own. And there was hardly a family ashore where the hand of death had not left its trace.

On the 5th of November the SS Corvello came in with fifty-one enlisted men for the Pittsburgh. These were immediately quartered on the Ilha des Cobras again with the insistence and courtesy of the Brazilians. Thus came and went that most terrible of experiences. The self-sacrificing spirit of our doctors and our men and the persistent kindnesses and consideration for our welfare shown to us by Brazilians in Rio have left with me and many an ineradicable memory. Suitable letters of appreciation and profound gratitude I later dispatched to the various civil and unofficial sources from which so much of our help had come, asking the Department at the same time to express to these people the Navy’s thanks for their self-sacrificing interest in us.

[END]

What about the men who were buried there?

Around the world there are many American graveyards from the various global conflicts we have been involved with.

But a story in the Washington Star from July 15, 1923 reveals an effort to bring the boys that died in Rio home.

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON/ D. C. JULY 15, 1923

Navy.

Another illustration of the Navy’s traditional “care for its dead” is found in orders just issued to the new cruiser Richmond to bring back to the states the bodies of twenty-two American sailors now buried at Rio de Janeiro.

During the flu epidemic in the fall of 1918 forty members of the crew of the U. S. S. Pittsburgh which was stationed at Rio died and were buried there until arrangements could be made to bring the bodies home. More than a year ago forty caskets were sent down, but it was found impracticable at the time of the Brazilian exposition to bring the bodies back.

Next of kin of all the epidemic victims have been communicated with and in the cases of eighteen of the men expressed a desire to have the remains interred in the crypt beneath the Pittsburgh monument therein the city. The other twenty-two will be taken aboard the Richmond when she touches Rio on her return from her cruise In European waters in September and will be brought to Hampton Roads to the Naval Hospital.

The caskets are under the charge of Rear Admiral Vogelsang, head of the American naval mission to Brazil, and instructions have been sent him by the department to arrange for the removal of the bodies from their temporary resting places in the cemetery there.

Final disposition of the bodies is necessary at this time as the five-year burial period required by Brazilian health authorities expires this fall, as well as the temporary leases of burial spaces. Under the Brazilian law it would be necessary to disinter and cremate the bodies at the end of the five-year period to make available the grave space.

Postscript:

Several years ago, I was at the Bremerton Naval Shipyard for the formal decommissioning ceremony of the submarine USS Pittsburgh (SSN 720). As I was preparing to leave, several news bulletins appeared about a strange new flu that was coming from China and spreading rapidly. Something called Covid 19. Despite the early warnings, flights out of Wuhan continued unchecke and centers of outbreak reflected much of that early travel. Similar to the spread of the first pandemic.

A few months later, like many others, I ended up becoming infected with the virus.

I was incredibly fortunate to be able to obtain the monoclonal infusion which promptly reverse the condition. Many people I know my age and older were not so lucky. The origins are still being obscured by people with an interest in hiding their own responsibility or knowledge. It would be a good thing if we had some truth so that the next pandemic will not have such a great impact.

Mister Mac

The following is a list of all of the crew members that died from October – November 1918.

Note: The Admiral’s report stated that 58 men perished.

The official list of dead can be found here:

https://www.naval-history.net/WW1NavyUS-CasualtiesChrono1918-10Oct3.htm

It was interesting to note that there are only fifty two names listed.

It is also interesting to note that not one of the names was an officer.

USS Pittsburgh, ex-Pennsylvania, armored cruiser (No.4, later CA-4), most of war in South American waters, all respiratory disease:

- WILLIAMS, EDWARD LAMAR, Seaman

- NEUHAUS, GEORGE, Chief Machinist’s Mate

- STEPHENS, MARION EDWARD, Fireman, 1st class

- NICHOLSON, HARRY AMBROSE, Chief Storekeeper

- CURRIER, ROLAND LEROY, Fireman, 1st class

- SAN LUIS, EGMIDIO, Musician, 1st class

- WHITTLE, JOHN, Fireman, 1st class

- FENLEY, DAVID EDWARD, Seaman, 2nd class

- FOEGLEY, WALTER LOUIS, Chief Machinist’s Mate

- HARTLEY, THOMAS BOWMAN, Fireman, 3rd class

- KNOWLTON, CHARLES WINSLOW, Boatswain’s Mate, 1st class

- RENFRO, ISS D, Water Tender

- WILKINSON, EDWARD WATSON, Gunner’s Mate, 1st class

- WILLIAMS, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, Fireman, 2nd class

- CHARON, EDWIN FREDERICK, Seaman, 2nd class

- COFFIN, HENRY SIDNEY, Seaman

- CRUDO, EUGENIO C, First Musician

- KRUSZKA, FRANK JOSEPH, Water Tender, USNRF

- BALINGAO, MARIANO E, Mess Attendant, 2nd class

- COCKRELL, ALEXANDER MILTON, Fireman, 1st class

- KEMP, JOHN ELSON, Coxswain

- KREH, CARL HERMAN, Chief Yeoman

- SCHAFER, BENJAMIN GEORGE, Seaman, 2nd class, USNRF

- WILLIAMS, GLEN ELMER, Chief Water Tender

- GALVEZ, ALFREDO, Mess Attendant, 2nd class

- HICKEY, JASON, Seaman

- McCARTER, JESSE BRYAN, Seaman, 2nd class

- McCOY, ALLISON JOE, Chief Boatswain’s Mate

- PERCIFIELD, ARLEY, Boilermaker

- PINKSTON, HARLIE MILTON, Water Tender

- STUART, BEN CHESTER, Seaman, 2nd class

- BRUNNER, FRANK, Seaman

- HART, LEONARD ANDREW, Ship Fitter, 2nd class

- HOUSER, ULYSSES SIMPSON, Seaman, 2nd class

- LILLEGARD, ELMER HEDEAN, Chief Electrician (R)

- ROSS, JOHN AARON, Fireman, 2nd class

- SHAW, WILLIAM JOSEPH, Fireman, 2nd class

- YANDLE, HARRY LESTER, Seaman, 2nd class

- EASLEY, WILLIAM JULIUS, Fireman, 1st class

- MILAYA, AGRIPINO, Mess Attendant, 1st class

- ELLIOTT, WILLIAM WESLEY, Seaman, 2nd class

- SMITH, WILLIAM MUNROE, Electrician, 3rd class (G)

- WATSON, GWYNNE LURVEY, Seaman

- BOND, EVERETT JAY, Boatswain’s Mate, 1st class, influenza

- PICKLE, WOODIE CLIFTON, Seaman

- STEWART, PERCY LEE, Seaman, 2nd class

- FOSTER, ARTHUR, Fireman, 1st class

- GILES, ELIGE MONROE, Fireman, 1st class

- BARRETT, JOHN WILLIAM, Fireman, 1st class

- NEGLEY, GUY PERRY, Fireman, 2nd class

- ROBERTS, THOMAS EDISON, Fireman, 1st class

- CARLTON, PAUL CAREY, Coxswain