The Surrender of Singapore and the Great Bluff

In the early chaotic days of World War 2, the Japanese took advantage of the fact that the allies had bartered away so many opportunities to prepare for a conflict. The Washington Naval Arms limitation treaty of 1922 resulted in smaller navies among the future belligerents, but also limited the number of defensive preparations that could have slowed down a hostile movement such as the one taken by the Japanese.

Singapore was supposed to be known as the Gibraltar of the Orient. The importance of this island chain was based on the natural resources available to whoever controlled it and the geographic choke points that could limit the flow of goods and materials from east to west and back again. Airfields could dominate the seas and bases for ships could be used for future conquests. That is the reason that the British did so much to reinforce the islands, even if it was somewhat belated.

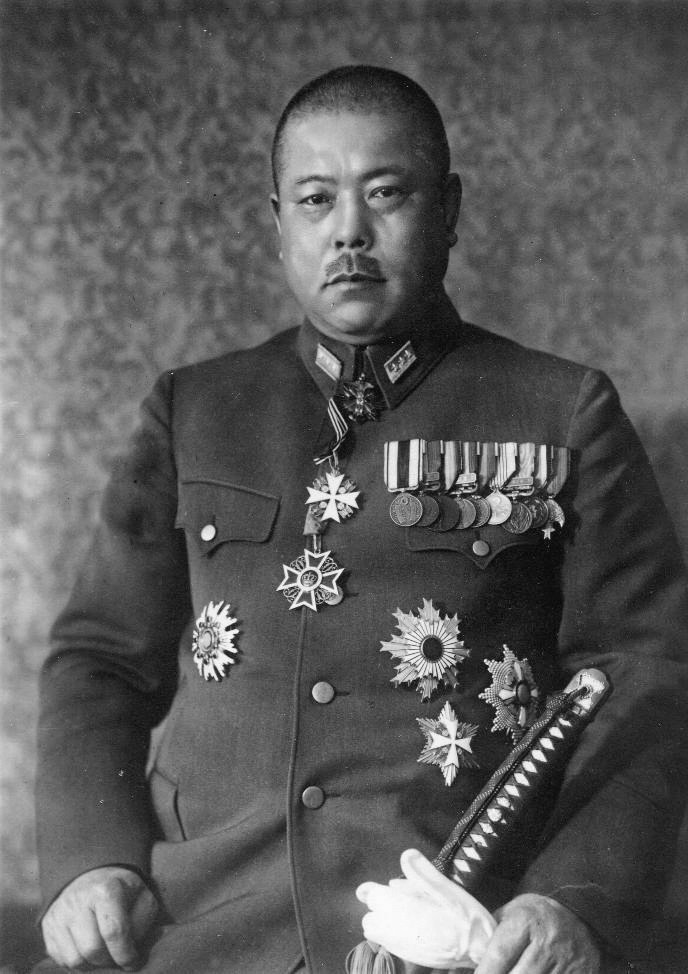

But the surprise nature of the attacks and the ferocity of the Japanese forces countered even the best preparations. General Yamashita was given a hard assignment, but he was determined to succeed. The takeaways from these reports from both official US Army records and contemporary articles was how good of a bluffer he was. It is also a very strong look at how future campaigns should be viewed in global wars.

Intelligence collection for the invasion of Malaya started in January 1941 on the island of Formosa, where a small unit was set up. Headed by Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, its purpose was to determine the requirements for successful tropical and jungle warfare. Over the next six months, the 10 man unit questioned area experts and specialists in all related fields and developed the necessary background for preparing troops to fight in the harsh jungle environment. Based upon his research, Tsuji reached three conclusions regarding the defenses in Malaya:

- Singapore Fortress was solid and strong facing the sea, but vulnerable on the peninsular side facing the Johore Strait;

- Newspaper reports of a strong Royal Air Force (RAF) presence were propaganda;

- Although British forces in Malaya numbered from five to six divisions (well over 80,000 men), less than half were Europeans

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/PTO/RisingSun/BicycleBlitz/index.html#IV

FALL OF SINGAPORE

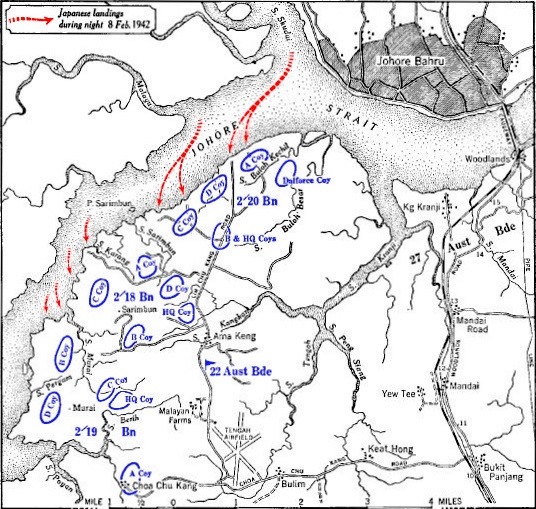

Yamashita took several days to conduct reconnaissance of Johore Strait and allow the troops to regroup prior to his assault on Singapore. During this time, the plan for invasion was developed. The Imperial Guards Division would make a feint attack to the northeast side of Singapore by landing on nearby Palau Ubin Island on 7 February. The 5th and 18th Divisions would remain concealed in the dense jungle until the evening of the 8th, when they would cross Johore Strait onto the northwest side of Singapore Island. Yamashita anticipated the campaign would be over within four days.

Although seemingly unstoppable, having conquered the 700 mile length of Malaya in 55 days, Yamashita was concerned about a possible protracted fight for Singapore. He had good cause to worry. He knew he could lose the upcoming battle for several reasons. First, he had lost over 4,500 personnel thus far and knew his remaining 30,000 men would have their hands full when facing the roughly 100,000 defenders of Singapore under GOC Lieutenant General A.E. Percival. Second, because of the exceedingly long supply lines, he had received little Japanese equipment since early in the campaign. The “Churchill stores” had been significant, but they could not hold out over a prolonged siege. Finally, his ammunition supplies were approaching critically low levels. Prolonged engagement would take him past culmination, and would bring about almost certain defeat. The battle for Singapore had to be finished quickly–and the British had to fall for his bluff.

“My attack on Singapore was a bluff . . . I knew that if I had to fight long for Singapore, I would be beaten. That is why the surrender had to be at once. I was very frightened all the time that the British would discover our numerical weakness and lack of supplies and force me into disastrous street fighting”

Across the strait, Percival had concerns of his own. Many of his numerous troops were poorly trained and equipped, largely non-European, and plagued by poor morale. The GOC speculated Yamashita would land in the northeast, but he was also fearfully aware that an attack could come from any corner: land, sea, or air. In response, he opted to attempt defense of the entire 80 mile island coastline.

The basis of the defense was that the enemy must be prevented from landing or, if he succeeded in landing, that he must be stopped near the beaches and destroyed or driven out by counterattack.

Defense of such a large area would be difficult for troops with the best training and the highest spirits, and Percival had very few of these. As British troops retreated toward Singapore, they were lifted by the thought of protection within the “Fortress.” However, unknown to many of the soldiers, there was no real fortress, save the seaward defenses of the naval base. Percival, aware that only a miracle could save them, attempted to raise the spirits of both soldier and civilian by telling them, “hold this fortress until help can come-as assuredly it will come . . .” In retrospect, help did not come for several years, and for those who died in Japanese prison camps, even that was too late. The defense that was as much a prayer as a plan was not enough to stop the Japanese.

Following the attack on Palau Ubin, the 5th and 18th Divisions proceeded as planned with the assault on Singapore. By sunset, Yamashita had set up his headquarters just north of Tengah airfield, five miles into the island and less than 10 miles from the outskirts of the city. The advance slowed, but the battle continued, and damage accumulated. Japanese bombing inflicted significant damage on Singapore’s reservoirs and water supply system. By the morning of 15 February, Yamashita ordered guns to be fired to the last round to keep up the pressure, but it was not necessary.

With less than 24 hours of water left to the defending soldiers and one million citizens of the island, Percival had already decided to surrender. At 1810 (local time) 15 February 1942, General Yamashita met General Percival to accept the British surrender of Singapore at the Ford Automobile Factory just outside the city.

From the Japanese Perspective:

TOKIO, Feb. 16.—A Domei dispatch from Singapore today gave this account of the surrender of Singapore: “Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, commander in chief of the Japanese expeditionary forces, dictating Japanese terms for the surrender of Singapore at the historic 49-minute meeting last night with Gen. A. E. Percival, commander in chief of British forces in Singapore, peremptorily accepted full responsibility for the lives of British and Australian troops as well as British women and children remaining in Singapore. “Declaring, ‘rely upon Japanese bushido (the way of the warrior chivalry),’ Yamashita demanded swift compliance with the Japanese terms for surrender “The following conversation took place between the Japanese and British commanders:

“Yamashita: ‘I wish replies to be brief and to the point. I will only listen to unconditional surrender.’

“Percival: ‘Yes.’

“Yamashita: ‘Have any Japanese soldiers been captured by the British?’

“Percival: ‘No, not a single one.’

“Yamashita: ‘What about Japanese residents?’

“Percival: ‘All Japanese residents interned by the British have been sent to India. However, their lives are fully protected by the Indian government.

“Yamashita: “I shan’t hear (I am 1 not asking) whether you wish to surrender or not, and if you wish I insist it be unconditionally. What is your answer, yes or no?’

“Percival: ‘Will you give me until tomorrow?’

“Yamashita: ‘Tomorrow? I cannot wait, and it is understood, then, that Japanese forces will have to attack tonight.’

“Percival: ‘How about waiting until 11:30 p.m. Tokio time (9:30 p.m. Singapore time or 10:30 an. Eastern war time)?’

“Yamashita: ‘If that is to be the case, Japanese forces will have to resume the attack until then. Will you say yes or no?’

“Percival was silent.

“Yamashita: “I want to hear a decisive answer, and I insist upon unconditional surrender. What do you say?’

“Percival: ‘Yes.’

“Yamashita: ‘All right, then. Cease firing must be ordered at exactly 10 p.m. I will immediately send 1,000 Japanese troops into the city area for maintaining peace and order. Can you agree to that?’

“Percival: ‘Yea.’

“Yamashita: ‘If you violate these terms Japanese troops will lose no time launching a general offensive against Singapore City.’

“The British made the first move for surrender at.2:30 pm., February 15, when three British officers including Maj. C. H. D. Wild, carrying a white flag, approached the vanguard of the main Japanese forces at a sports ground four kilometers north of the Bukit Timah road, and proposed to discuss terms and conditions.

“At the instruction of Lt. Gen. Yamashita, unit commander Sugita interviewed the British officers, whereupon he rejected the British truce proposals and advised unconditional surrender, adding that if the British commander was willing to surrender, the commander in chief of Japanese forces would discuss terms and conditions the same day. “The British officers retired at 4:15 p.m., meanwhile, guns continued to roar from Japanese and enemy positions. At 6:40 pm. the same day Lt. Gen. Percival, accompanied by chief of Staff K. S Torrance and MaJ. Wild, motored to the Ford Motor Co. plant carrying a large union jack and a white flag. They were escorted by Unit Commander Sugita. “No sooner had the British officer taken seats in one of the rooms at the plant at 7 p.m. than Lt. Gen Yamashita appeared, accompanied by several staff officers, whereupon the British and Japanese officers shook hands and the meeting commenced.

In London, Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced that the fall of Singapore was the ‘worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history’.

Despite being heavily outnumbered, the Japanese moved quickly across the island. With one million citizens trapped in the city and water supplies at critical levels British commander Lieutenant General Arthur Percival surrendered on 15 February 1942. More than 130,000 Allied troops were taken prisoner.

Aftermath

The Japanese occupation of Singapore started after the British surrender. Japanese newspapers triumphantly declared the victory as deciding the general situation of the war. The city was renamed Syonan-to (昭南島 Shōnan-tō; literally: ‘Southern Island gained in the age of Shōwa’, or ‘Light of the South’).

The Japanese sought vengeance against the Chinese and anyone who held anti-Japanese sentiments. The Japanese authorities were suspicious of the Chinese because of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and murdered thousands in the Sook Ching massacre. The other ethnic groups of Singapore—such as the Malays and Indians—were not spared. Residents suffered great hardships under Japanese rule over the following three-and-a-half years. Numerous British and Australian soldiers taken prisoner remained in Singapore’s Changi Prison and many died in captivity. Thousands of others were transported by sea to other parts of Asia, including Japan, to be used as forced labor on projects such as the Siam–Burma Death Railway and Sandakan airfield in North Borneo. Many of those aboard the ships perished.

British forces had planned to reconquer Singapore in Operation Mailfist in 1945, but the war ended before it could be carried out. The island was re-occupied in Operation Tiderace by British, Indian and Australian forces following the surrender of Japan in September.

Yamashita was tried by a US military commission for war crimes but not for crimes committed by his troops in Malaya or Singapore.

He was convicted and hanged in the Philippines on 23 February 1946 (four years after his bluff)

It’s interesting to see how current events often parallel what has happened in the past, but it’s also interesting to see that good ultimately wins in the end.

Mister Mac

Hello from the UK

Many thanks for this post. By the way my dad was in the Royal Navy and was a T.A.S officer for a while. I did my own post recently on the fall of Singapore and had not seen a transcript of the conversion between the two generals, very interesting.

Percival is recorded as saying he did not have defenses built on landward side because it would be bad for morale. I found that incredibly stupid. A good general should always make contingencies to protect the back door as I put it in my post.

If you should be interested, here is my link. I take a different route by presenting a humourous side to these black events, at least in part. However, not the massacre of the nurses and wounded at the hospital or indeed the torture etc of POW’s and civilians alike which was reprehensible and vial.

https://alphaandomegacloud.wordpress.com/2022/02/15/the-battle-for-singapore-or-fall-of-singapore/

Kind regards

Baldmichael Theresoluteprotector’sson

Please excuse the nom-de-plume, this is as much for fun as a riddle for people to solve if they wish.

Thanks for the note and the information. I spend a lot of time in the Smithsonian Archives researching the odd and unusual stories recorded in newspapers that are electronically stored there. As I read the stories, I am often reminded of the bias of the reporters, the newspaper owners and sources they use. The conversation recorded is form a Japanese war time newspaper and would reflect their particular bias. I had never seen this conversation in print either so that added to my offering. I wonder if Percival would agree with the portrayal given by the writer regarding that particular conversation.

Thanks again and I will check out your link

Mac

Thank you for that additional information. I gather Percival did write memoirs.

I have just found this link which may be of further interest.

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2016/06/17/general-percival-a-convenient-scapegoat/

I think it sums up the situation nicely. The army was never the First Service as the RN was and is. I may be biased, but as an island nation it seems obvious this must always be the case. So the army didn’t get the best all too often, and suffered as a consequence.