Cold War Stories – Prepare to Snorkel

When the word is passed “Prepare to Snorkel” on a submarine, a number of actions need to be taken immediately. The boat has to be at the correct depth, valves need to be adjusted and of course, the diesel operator needs to do some preliminary actions. The snorkel mast is raised and the control room party is keenly aware of depth control in order to keep the snorkel mast head in a position that it will allow air to flow to the monster below.

The sea state can be a tricky thing since the boat’s position in relation to the surface can be affected and the mast may dip below the waves. Once the diesel is running, any interruption to the flow of air means the diesel will need to take a suction on the inside of the boat. There are safety devices which prevent the diesel from taking too great of a suction. That would impact the crew in a very negative way as well as impact other equipment.

I do not remember doing very many snorkel operations underway on my first boat which was a boomer. The use of the diesel did come in quite often when we were tied up next to the Proteus. In port, we relied on shore power but more often than not, we would lose shore power, and the diesel would be needed to provide power. The memory I have is that when it lit off, black smoke mixed with oily water would come shooting out of the exhaust and it happened with the whole off duty crew topside in whites and in formation waiting for change of command. Wonderful timing.

I do remember doing a lot of snorkel operations on my third boat which was a fast attack. Not because of the reliability of the reactor so much as exercising the crew during drills and other training evolutions. The great thing about the diesel is that it would provide a reliable source of power for short term use and often times in overseas ports would be used to give the nucs a chance to do needed work with the reactor shut down.

But in the early days of the Cold War, diesel power was still king and lessons from the great war showed that the ability to snorkel was a great leap forward. Having the ability to continue running the diesels while submerged would greatly reduce the risks of having to operate on the surface in a hostile environment.

Some additional history extracted from Warship International Volume 41 Numbers 1 and 4. “Now Hear This” column by Mr. C. Wright.:

Several snorkel systems or snorkel-like systems were installed on board US submarines. Simon Lake used an engine exhaust system that utilized a pipe extending above the main deck aft. The Alligator (1862) had an ‘air tube’ to allow air to be drawn into the boat while it was submerged at a shallow depth. The CSS Hunley had a similar air tube system. John Holland’s Plunger (1898) was to have a coiled hose system which had a float to permit air to be drawn in from a deeper depth than either the Alligator or Hunley.

The snorkel system design and testing program for what can be called the ‘standard submarine snorkel’ is summarized below:

Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (Kittery, ME) performed the design work on a snorkel system as an independent design using captured blueprints and a snorkel mast system captured in Toulon, France. CNO directed, on 20 January 1945, that an accelerated design and build program be instituted and an R-Class submarine be selected for experimentation (this is equivalent to the Engineering Development Model in today’s language). [CNO letter of 26 January 1945].

The R6 was selected and the snorkel was fitted in Portsmouth during the period 10 April to 20 May 1945. The system was tested and provided information on the effects of the snorkel on personnel and equipment. Piping was installed on the main deck for simplicity and the snorkel mast was fixed in an upright position. R6 took the system to Florida in August 1945 for testing in an ASW setting. The boat operated for three days in southern waters (out of Ft. Lauderdale) during the period 3 to 25 August 1945 and three major engine casualties were reported. However, it is unknown whether these were due to the snorkel or were due to other factors such as age and maintenance. The system’s components were removed prior to the decommissioning of the boat in September 1945.

The next testing phase was held aboard the USS Sirago (SS-485) immediately after her commissioning (Commissioning was on 10 September 1945). Preliminary tests took place at Portsmouth during the period 11 to 13 September 1945. The tests were to determine if the design was adequate and the effect of snorkeling on diesel engines and personnel.

Sirago had four Fairbanks Morse 10-cylinder D38 8-1/8 engines numbered 848587 through 848590. Only one engine was fitted with the exhaust ducting for testing, number 848588}. The tests on 11 September tested the machinery, calibration of the measurement equipment and personnel orientation. Engine standardization runs were carried out on the 12th. These included runs at snorkel depth (alongside) to determine the effect of the varying back pressure on engine speed and loading. On the 13th runs were made which simulated wave action on the (float type) head valve cycling. The system was dismantled starting on 17 September.

Electric Boat Company had been designing their own snorkel system. They asked the Navy to provide the data that had been compiled during the testing of R6 and Sirago. The company proposed on 12 June 1945 that a system be put aboard either Clamagore (SS-343) or Cobbler (SS-344). The Navy Inspector of Shipbuilding selected Clamagore. However, in Electric Boat’s opinion the Clamagore was too close to completion and pushed for the Cobbler in a test plan dated 19 June 1945. BuShips approved the plan on 4 July 1945. The test was not a full snorkel system but a pressure variation test using just the power operated head valve. The head valve was to be fastened to a plate which was then mounted on the after-engine room hatch. However, in the builder’s underway trials (prior to the head valve testing) the lube oil systems of the four main engines had problems and the testing was delayed. Electric Boat withdrew from further snorkel design for fleet submarines.

The Irex (SS-482) received the first ‘full up’ snorkel system in Portsmouth Naval Shipyard starting in December 1946. The system was evaluated in extensive testing during the period July 1947 to February 1948. She was then the first US submarine to become operational with a snorkel.

The following article was from the ALL HANDS Magazine January 1949. It traces the development of the idea of snorkeling from the early days of submarining to the early Cold War period.

From the Article:

CONTRARY to current belief, the submarine breathing apparatus known as snorkel is old enough to be its own grand paw.

As an idea on paper, it harks back 120 or more years ago. As a workable gadget for peacetime use, it first appeared on Simon Lake’s submersible creation of half a century ago. As a practical improvement in underseas warfare, the breathing gear emerged in perfected form on Dutch submarines prior to World War II.

None of these milestones of development was contributed by the Germans. Although the German Navy made good use of breather-fitted craft toward the end of World War II, recent evidence seems to indicate that ideas from captured Dutch submarines and not German ingenuity prompted their development of snorkel.

Even though Allied naval officials in London knew the Dutch equipment had fallen into German hands, they were not upset by the prospects. Their considerations probably were:

(1) breathing equipment for submarines was not radically new, and

(2) its use would impose so many handicaps that the German Navy would resort to it only as a means of desperation.

That last resort was at hand with the advent of radar search planes which could cover large areas in a short time to detect enemy submarines at great distances.

On the other hand, the Allies also knew of the Dutch gear, for three Dutch submarines equipped with the breathing apparatus arrived in English ports while the battle for Holland was still in progress in May 1940.

No attempt was made during wartime to fit out Allied underseas craft with comparable devices, since it was not necessary. Had the Japanese perfected submarine detection to the same extent as the Allies, there is a good possibility that American and British craft would also have been fitted with breathing devices evolved from the Dutch model.

While both fleet – type and newly constructed American submarines today are being fitted for exhaustive testing, snorkel still imposes many hardships and problems in submarine operation.

Some of these are long standing difficulties, inherent in the earliest conceptions of the gear. Back in 1827 a French submarine authority by the name of Castera took out a patent for a salvage boat equipped with a float which would ride on the surface while the craft proceeded submerged. Two aeration tubes were mounted beside the conning tower, leading upward to the float. As the submarine dove to deeper water, the aeration tubes lengthened to allow freedom of movement.

In the bottom of the craft were fitted several lookout portholes of thick glass and a pair of heavy leather gloves, which would enable the occupant to pick up such items as might be seen on the bottom of the sea or river.

Although the boat was never constructed, its considerable hazards were apparent.

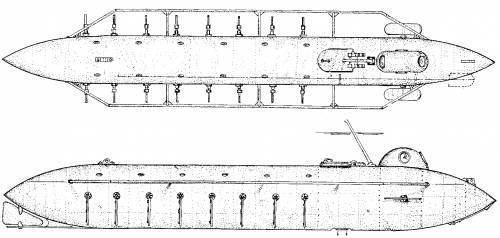

A similar underwater salvage craft was devised by an American named Roman Morhard in 1885. According to plans, air was to enter the interior of the boat from the surface through two small floats connected to the submarine by flexible rubber tubes.

Perhaps fortunately for the inventor, the craft never reached production stage.

Many inventions had come into use providing for an internal supply of air long before the time of Simon Lake, the American inventor of considerable prominence, his Argonaut was equipped with both an internal compressed air supply and ventilating tubes leading to the surface.

Argonaut’s first public trials were held in the Patapsco River near Baltimore, and the following year Lake and a crew of four took off for extensive tests in the Chesapeake and shallower reaches of the Atlantic.

Fitted with wheels, Argonaut was able to submerge and run along the bottom while the crew amused themselves by standing over the opened diver’s hatch to pick up sea shells, oysters and whatever else might be found. The internal pressure of the diving compartment equalized the water pressure to prevent flooding.

As a boy of 10, Lake had become obsessed with the idea of building a submarine after reading the famous book by Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, dealing with the activities of a submarine which chemically derived its oxygen for human and engine use from the surrounding water, and thus was capable of staying submerged as long as desired.

Argonaut returned from her voyage after cruising nearly 2,000 miles, and Verne joined the rest of the world’s applause by sending a cablegram from France: ” While my book is entirely a work of the imagination, my conviction is that all I said in it will come to pass. The lengthy voyage of the Baltimore submarine boat is evidence of this …. The next great war may be largely a contest between submarine boats. ”

Lake’s Argonaut was fitted with a 30 – horsepower gasoline motor for motive power and with two steel tubes in which compressed air could be stored, lasting in use for 24 hours. Wherever possible, however, the craft operated on air supplied through a hollow mast while another mast expelled exhaust gases from the engine. For emergencies, Argonaut also could rely on a buoy, which would rise to the surface and allow air to flow down its hose.

While the earlier ancestors of snorkel were concerned only with peace-time operations, it was not until 1927 that a Royal Netherlands Navy officer, Lieutenant Commander J. J. Wichers, now retired, began to evolve the mod- ern concept of the ” submerged dieseling system. ”

According to written material from the Netherlands Naval Information Service directed to ALL HANDS, Wichers perceived the need of some device to increase the submerged speed of the submarine. In the 30 years from 1904 to 1934, merchant vessels had been able to double their speed while the output of the electric battery system of propulsion in underseas craft remained essentially unimproved.

With the increasing difference in speed, the angle of attack for the sub- marine was growing smaller through- out the years. A diagram emphasized this to Wichers with graphic clarity- for instance, a submarine which had been able to stalk her prey from an angle of attack of 61 ° in 1904 would have had only 22 ° under the same conditions in 1934, because of the greater disparity in speed.

“This angle could be increased,” the translation of the Dutch account reads, “if the submerged submarine would be able to sail on diesel engines, which would be made possible if air could be obtained. Lieutenant Commander Wichers then conceived the idea to make a pipe protruding above the surface of the water, through which the engines could inhale their breathing air. ”

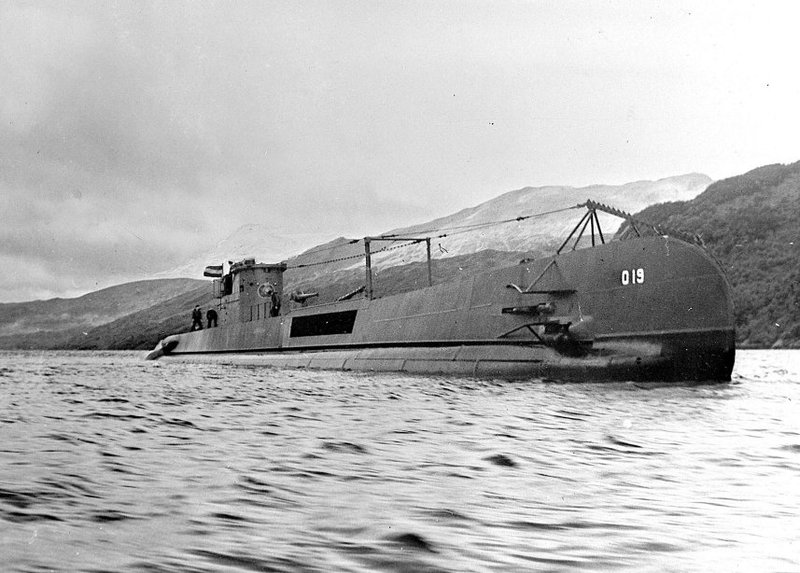

For six years Wichers continued experimenting with this idea, at the end of which it was presented to the Commander in Chief of the Netherlands Naval Forces in the Dutch East Indies. “The aim of the plan,” the information notes,” was to change the attacking tactics of the submarine. It could reconnoiter a target, then steam on the surface towards a forward position, then approach on engines while submerged, while the main attack would be carried out on main motors. ” By 1937 the Dutch Navy had two submarines, designated 0-19 and 0-20, fitted out with the new apparatus. ” On these boats, ” the Dutch say, ” the difficulties were mastered and the apparatus appeared to be a great success. ” Wichers found the angle of attack had increased back again to 65 °, or a few degrees more than in 1904.

When war broke out in May 1940, with a five – day blitzkrieg of Holland, the new submarines 0-21, 0-22, 0-23 and 0-24 escaped to the United Kingdom but Wichers personally states that ” unfortunately the apparatus was demolished directly after arriving there. ” The crew of 0-25 scuttled their craft in Holland, but the Germans marched in to take possession of 0-26 and 0-27. ” To all probability, ” the information states, ” the Germans also captured the building drawings and they could reconstruct the invention. ”

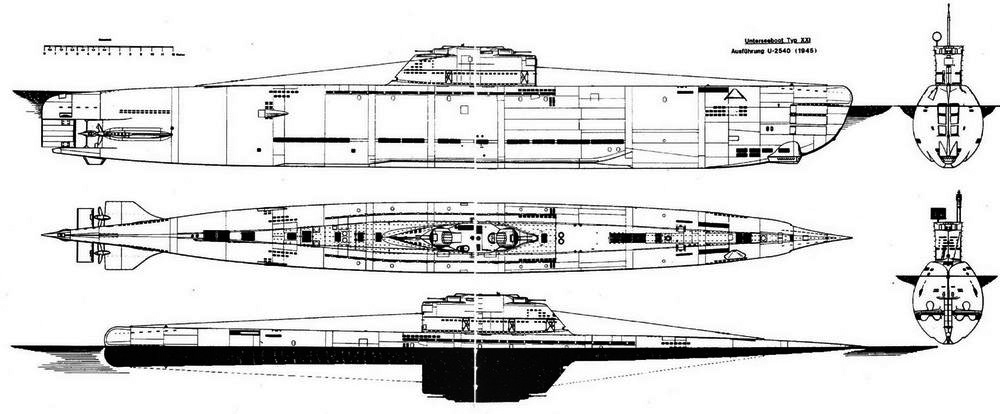

In the years that followed, the Germans made prodigious progress and by September 1944, their new Type XXI submarine, fitted with snorkel and larger batteries which doubled their submerged speed, began to appear in operations.

The impact of the snorkel – fitted Type XXI was summed up by Rear Admiral Charles B. Momsen, USN, Assistant CNO for undersea Warfare: ” With this device, submarines were not required to come to the surface to charge batteries. ”

Radar had occupied a large part of the Germans ‘ worries, and in snorkel they had a potent weapon against it. Fitted with snorkel breathing masts, the Type XXI subs were believed by the Germans to be only one – third as susceptible to radar detection as com- pared with types which were forced to surface to charge their batteries. By covering their snorkel and periscope with rubber coatings, they estimated that chance was lessened to one- ninth.

Airborne radar had forced Nazi subs out of the English Channel and other concentration points. Now, with snorkel, they were able to return, remaining on the bottom most of the time and ascending only to snorkel depth to recharge batteries.

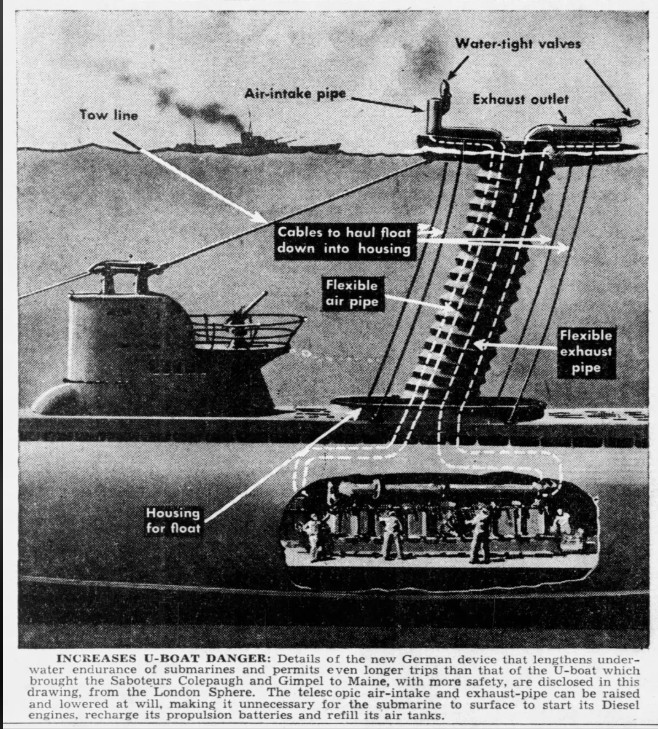

The air came in an intake trunk, and a diesel exhaust lead expelled vitiated air from the engines. At the top of the mast and forming the head of the intake pipe was a floater valve which closed when water entered, thus shutting off the compartment until the pipe was free.

German success in the use of the device varied considerably. While U – 1229 was able to proceed in the North Atlantic for more than 14 days. surfacing only 10 or 15 minutes each night to take navigational sights, and U – 300 could cross the North Sea in only nine days largely because of snorkel, their compatriots in other vessels were having troubles.

Men from U – 715 reported their snorkel floater valve would close for long periods causing the diesel motors to use up oxygen at a tremendous rate creating a vacuum and producing ear trouble, nausea and complete exhaustion among the crew.

The same valve defect resulted in diarrhea among the crew of U – 269, and diesel exhaust fumes frequently flowed through their compartments. Another U – boat, operating in the English Channel, frantically radioed Ger- man submarine control that two – thirds of her ship’s company was suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning through use of snorkel.

The problem of maintaining trim also seemed to plague U – boat commanders, for the snorkel intermediate valve in many boats allowed a constant trickle of water to enter the submarine, necessitating the use of pumps. The detective powers of radar diminished as snorkel increased detection difficulties, and American anti – sub chasers came to rely more on visual sight, for the snorkel always left a tell – tale track of smoke and haze.

Efficient or not, the new Type XXI was the last hope of the German Navy to recapture the glory of former wolf-pack days, and during the winter of 1943-1944 the entire resources of Germany were channeled into production of this submersible.

By that time, Allied planes were clouding German skies, and both industrial and naval centers were rocking under the impact of the block- busters. The Type XXI subs which had already been launched were experiencing many design difficulties which hampered their operations.

Germany was on the skids, irretrievably. Even their new Type XXVI, a radical design for which they estimated the astounding submerged speed of 26 knots through use of hydrogen peroxide for both engines and crew, could not have changed the tide had they been ready sooner.

While snorkel was an important innovation in 1944, its postwar luster is both over polished and fading as new countermeasures reach perfection. In this winter’s fleet maneuvers off Argentina, only one warship fitted with modern gear was ” lost ” while five snorkel subs were ” sunk, ” even though they had a tremendous planned advantage in and weather conditions and operational information.

The U.S. snorkel is greatly superior to the German production of the Dutch original, and the Navy’s new anti – sub (and anti – snorkel) devices highly perfected secret unequaled by any other nation. In the meantime, the Navy is pushing research on new types.

It’s a distinct possibility that snorkel, which arrived in World War II too late, will soon be outdated.

The prediction of obsolescence in 1949 may have been a bit premature

The birth of the Nautilus included a backup diesel generator and famously, on her initial voyage, the diesel was used for a short time when the reactor did not behave on her first voyage. Every submarine built during the cold war included a diesel generator and to the best of my knowledge all naval nuclear reactors currently in use are operated with diesel generators as a backup power system. Snorkeling is certainly as much a part of submarining as is any other technology.

There are some newer technologies that are emerging now that extend the underwater operations of non-nuclear submarines.

But for the time being, Prepare to Snorkel will remain a part of submarining.

Mister Mac