In 1940, the American navy was advertised as one of the most powerful in the world.

In a speech to the Navy Council of Illinois in Chicago on Oct. 26—Secretary of the Navy Knox asserted that the United States “has the most powerful fleet in the world and is engaged in the task of building sea defenses strong enough “to stand off any combination of enemy.” He asserted that “maintenance of naval supremacy would be a contribution to peace in a world that would be “ruled by force” for a generation.”

Speaking of strategy, Secretary Knox said that the best defense is that in which “the enemy force is sought out and destroyed.” “The fleet that we are now building is designed for defending America by keeping attack from our own shores and carrying it to the shores of the enemy. That is the American way.”

The winds of war had already started blowing with ferocity on both sides of the world. And Secretary Knox knew exactly how far behind the country was in its preparedness.

Decades of neglect were coming to haunt planners as they realized that adherence to treaties had already cost the nation precious time.

The submarine force was no exception. Not a single new submarine was built in the early 1920’s and the ones that were built up until the late 1930’s was not well designed or equipped for the role they would need to play in the future. The planners still saw submarines as a defensive weapon and not as free ranging fighters that could independently wreak havoc on an enemy fleet or commerce ships.

The submarine building industry had also been seriously shackled during the period between years. Like any major shipbuilding efforts, losing the skills and supply chain would mean years of catching up. Plus, newer technologies that would be needed to build and support a modern submarine were left to atrophy. In simple terms, the country was not ready to wage war or defend itself in a way that was sustainable.

Catching up

Recognizing that the world was sliding closer to a complete global conflict, the administration and congress finally threw off the chains of the now worthless treaties.

Funds were allocated and direction was given to rapidly build the infrastructure needed to build new warships and submarines.

The following two articles talk about how things were done.

Vast Plant Expansion Started to Build Two-Ocean Navy

$131,000,000 Spent, More to Come, On Facilities to Increase Fleet

Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 27 Oct. 1940. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1940-10-27/ed-1/seq-6/

With many millions yet to spend, the Navy has made a down payment of S131,000,000 on the enormous expansion of shipbuilding facilities which the Nation will need to complete its two-ocean fleet. The magnitude of the key problem involved in building the world’s greatest Navy is illustrated roughly by the fact that, when the 70 per cent naval expansion was projected, the United States had only 83 available shipways on which to lay the keels of 312 vessels. Many of them in disuse, these ways were located in eight Navy and eight privately owned shipyards which were building or had built combat vessels, and in five other private yards which could undertake Navy work “within a reasonable time.”

More Facilities Started.

Many more ways obviously were needed. How many, the Navy Department would not say, but it started spending money. Amounts allocated so far indicate that 15 to 20 new ways and docks may be constructed immediately. Exact numbers and locations were not disclosed. As the program progresses, additional facilities may be provided.

Contracts thus far announced include $16,000,000 for new facilities at the Norfolk and Philadelphia Navy Yards, plus about $115,000,000 for construction at Government expense in 19 private plants, including steel mills and shipyards. In lay terms, a shipway might be described as a permanent scaffold which supports the keel, framework, and hull of a vessel while it is being built. Drydocks and floating docks can be used. In some cases, for the same purpose.

Takes Years to Build Hull.

Each building way should have close at hand all of the machinery, equipment and supplies for construction—cranes, wharves, tools, machinery, power, machine shops, storehouses, etc.

When the completed hull of one ship is launched from a shipway or floated out of dry dock, the keel of another can be laid down in its place. It is not necessary to have as many ways as there are ships to build.

But it takes months and years to build a hull to the point of launching. The usual practice with shipways is to launch a vessel when it is 60 to 65 percent complete. Often, long preparations must be made before a new keel ran be laid.

With drydocks. a vessel must be nearly finished before it is floated out. It has taken from two years to two years and nine months from keel-laying to launching of the Navy’s two newest battleships; 9 to 11 months for new submarines; 7 to 11 months for new destroyers. 48 Months for Battleship.

All told, it takes 42 to 48 months to build a battleship. 34 to 48 for an aircraft carrier. 32 to 39 for a 10,000-ton cruiser. 24 to 36 for a destroyer and 18 to 25 or more for a submarine.

The wide variance in time is due to differences between the facilities of various yards and between normal peacetime working schedules and employment and those of an emergency period. An all-out effort is being made by the Navy to reduce building schedules to the absolute minimum in every instance with the aim of putting the bulk of the two-ocean fleet in service in 1944 and the entire armada by 1946 Including 200 combat vessels provided in the 70 per cent expansion act and others previously appropriated for. The Navy has 330 fighting ships to build.

Note: The attack on Pearl Harbor would change the timing dramatically. All of the old plans were scrapped and new things previously thought impossible would become reality.

Five Yards Need Ways.

The total of 83 ways includes 21 in the five yards without current Navy shipbuilding experience which must build new ways or rehabilitate old ones (new ways obviously will be built in sizes to accommodate ships for which the yards hold contracts.

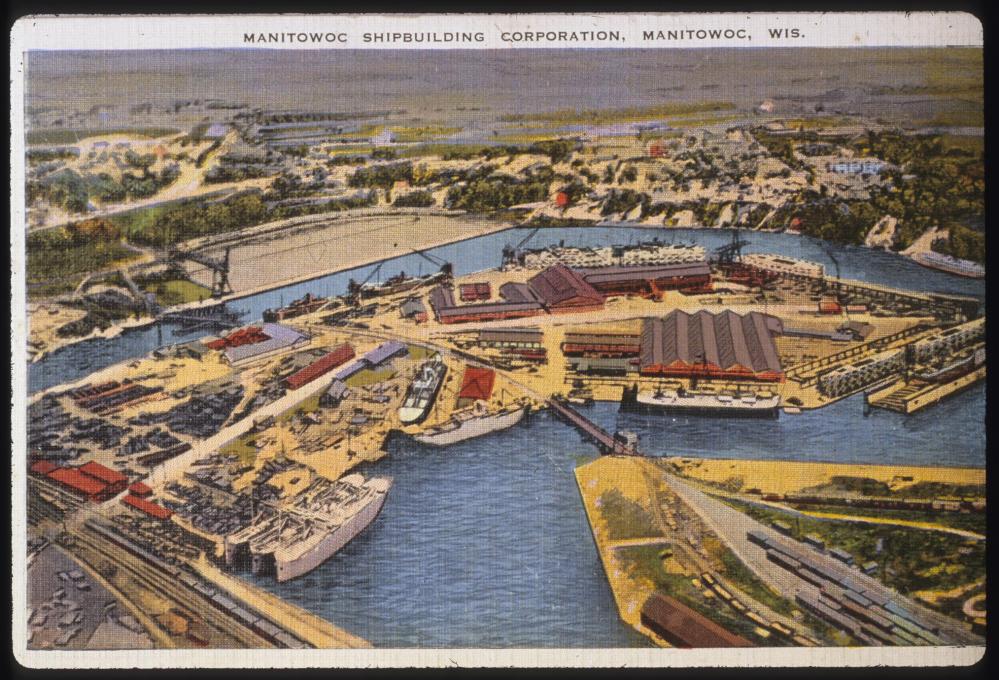

Those five are Bethlehem Steel Co. at San Pedro. Calif.; Seattle- Tacoma Shipbuilding Co. Seattle, Wash: Consolidated Steel Corp Ltd Orange, Tex.; Manitowoc Shipbuilding Co. Manitowoc. Wis and Gulf Shipbuilding Co., Chickasaw. Ala. All of them received funds for additional facilities, in contracts recently announced, as did the other 16 companies which hold orders for combat ships. At least nine of the 21 needed new ways: others did not. Some yards merely will extend or rehabilitate old ways.

Building a modern submarine requires technical expertise and experience in assembly.

With the paltry efforts to maintain and develop submarine, building a supply chain is not as easy as just pouring money into the effort. Identifying the right vendors and equipping them was especially challenging since only Electric Boat in Connecticut had survived the drought. Issues like how many boats and how much capacity EB had would challenge the government planners. Plus, like any major company that held patents on processes and equipment, their reluctance to share was understandable. I can only imagine the pressure that was put on them by the government as they struggled to come up with the right amount of submarines that would be needed.

A number of yards around the country would eventually be tapped to make up the shortfall. But one of the most interesting was the Manitowoc Shipbuilding company.

This is an excerpt from a well-researched book about submarine construction.

Forged in war: the naval-industrial complex and American submarine construction, 1940-1961 / Gary E. Weir

Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company

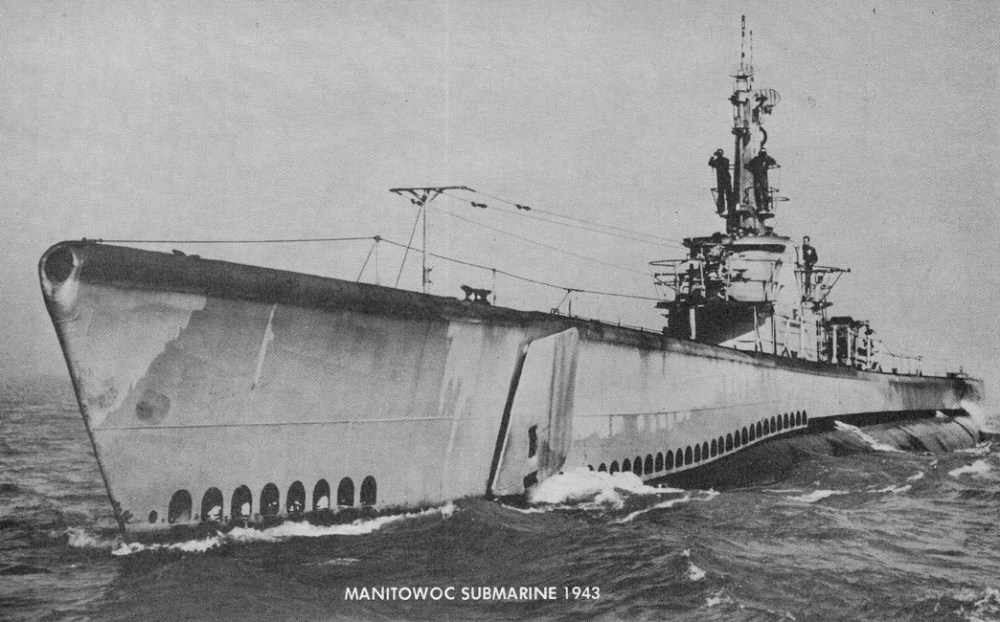

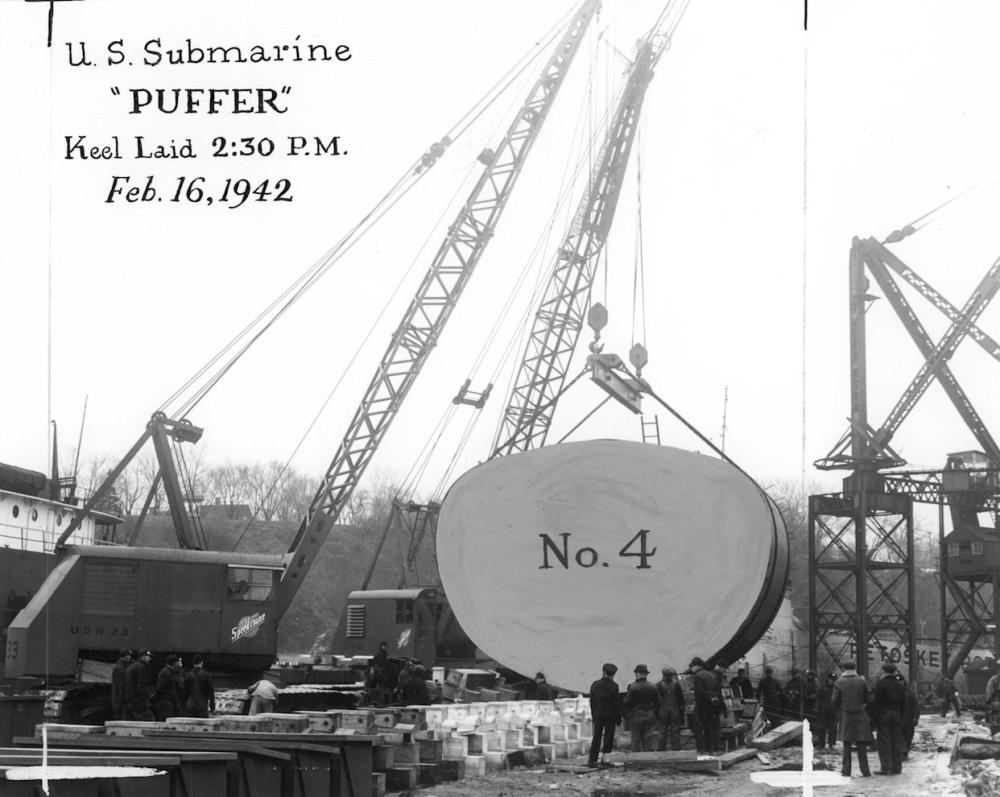

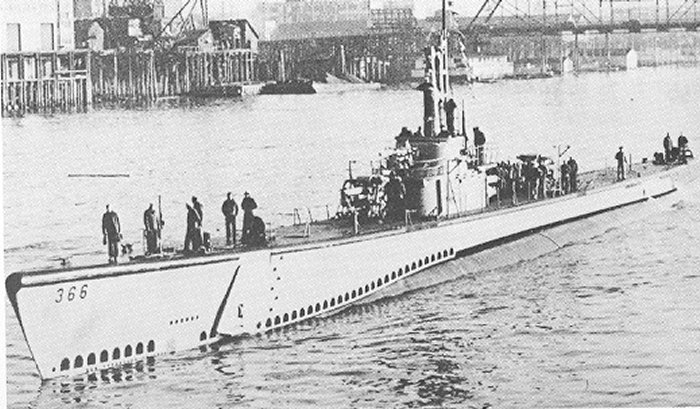

“In 1940 BUSHIPS drew another private contractor into the submarine business as a support facility for EB. The Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company entered into an agreement with the Navy in September to build EB sub- marines under license. The bureau decided to pursue a long production run with the Gato – class submarines; Manitowoc would provide the Navy with duplicates of its Growler (SS 215) design, first produced by EB at Groton. MSC would employ this submarine as a prototype for the SS 265–274 series, using EB patents, supervision, training, and special systems installation.

Building submarines on the western shore of Lake Michigan inspired some interesting innovations in construction and delivery. To permit year-round work, MSC built its submarines in segments inside heated construction sheds. The sections then traveled to the ways by mechanical doodlebug, or tractor – mover. Here the yard force installed the machinery and welded the hull sections together. The company then slid the vessels sideways into the Manitowoc River, a waterway too narrow to permit the traditional stern – first launch. After each submarine passed acceptance trials in Lake Michigan, MSC turned the vessel over to the Inland Waterways Corporation, which brought each boat down the Mississippi River to New Orleans on a barge from Lockport, Illinois.

This arrangement initially placed a considerable burden on Electric Boat. The company agreed to “license Manitowoc under all patents owned or controlled by it which may be used in the construction of the said ten submarines.” In addition to providing experts to supervise and assist in the construction at Manitowoc, EB negotiated with its Gato – class subcontractors for the purchase of materials required by MSC. The Groton firm even carried the insurance that protected the vessels after they reached New Orleans and began the final stage of their trip to Groton. Once the submarines arrived, EB had to install the periscopes and masts. All of these services were rendered for a sum equal to their cost, plus a fixed fee of $ 126,560.52

The advantage of this arrangement to the Navy was the speed and simplicity in acquiring a large number of submarines in the most cost-effective manner. Secretary Edison and his successor, Frank Knox, believed this plan would save design and construction time and the expense of new tools and equipment, spare parts, planning, and testing.

The Manitowoc agreement proved successful in spite of some initial difficulty. Although Electric Boat cooperated with BUSHIPS as the plan unfolded, the company exhibited a degree of reluctance to extend to the new contractor all of the supervisory and technical assistance the agreement required. Although its directors negotiated for Manitowoc, Groton refused to place orders or guarantee that its private subcontractors would offer Manitowoc the same prices EB paid on long-term projects. Electric Boat expected few of its suppliers to sign a long-term agreement without some provision for rising costs and prices.

These circumstances caused a certain degree of tension between the staff at MSC, led by Charles C. West, MSC’s president, and the visiting experts sent by EB, under its agreement with Manitowoc, to give advice on submarine construction. According to observations made by Commander Armand M. Morgan, wartime director of the Submarine Section of BUSHIPS, West and his staff did not like the attitude of the EB advisors. At the time Commander Morgan noted that ” neither Sup ship, Manitowoc (Cmdr. Weaver) nor Mr. West want EB Co supervision. “Mr. West has privately told me that he resents EB Co attitude of ownership.” This kind of friction was to be expected in an unusual relationship of this sort. Electric Boat took exception to the idea of aiding a possible postwar competitor, but in the end, it reluctantly fulfilled its contract obligations.

Considerable administrative costs represented an important reason for EB’s lack of enthusiasm for its role in the Navy Department’s plans for Manitowoc. On the strength of naval investment in the company’s facilities and the promise of new contract awards, EB became a conduit for much of the material and many of the systems needed to build the company’s Gato – class designs. BUSHIPS permitted Manitowoc to make local purchases of those items not peculiar to EB designs. But the Groton firm had to negotiate the procurement of unique materials and systems for all of the yards using EB Gato plans, billing the Navy Department at cost and absorbing most of the labor and administrative charges.”

A first time for everything

Manitowoc had never built a submarine before, but the first was completed 228 days before the contract delivery date. Contracts were awarded for additional submarines, and the last submarine was completed by the date scheduled for the 10th submarine of the original contract. Total production of 28 submarines was completed for $5,190,681 less than the contract price.

Employment peaked during the military years at 7000. The shipyard closed in 1968, when Manitowoc Company bought Bay Shipbuilding Company and moved their shipbuilding operation to Sturgeon Bay.

Recently, a group of my Charleston SC Submarine Veterans Base travelled to Manitowoc for a sub fest. The link to the locally published story is here:

I have been concerned over the past decade as I watch the US fall further and further behind other industrialized nations in submarine and shipbuilding capacity.

Particularly the Chinese as the race to become a true global sea power. We were fortunate in 1940 to have had just enough capacity to rapidly build up the forces that would successfully prosecute the war.

I am very concerned that we might not have enough time to do so again.