It’s the little things in life that make you think.

One of the nice things about the new house is that the first owners traded up on a number of things in relation to the construction of the house. One of those items is a very large shower stall. It’s got enough room for several people at a time and features one of those oversized shower heads that delivers a rain of shower of water. Heck, it’s so nice it would probably make a sonarman blush. (submarine humor – sorry Harry).

I was applying my shampoo and after applying it, my eyes were closed to prevent the soap from getting in them. I instinctively put the bottle down on the shelf (without looking) and kind of surprised myself that I did it without knocking anything else down. Without looking, my arm automatically knew exactly where to put the bottle despite the fact that we have lived here less than a month. I got to thinking that “learning to see” even without being able to use my eyes was a learned skill from many years ago.

Boot Camp

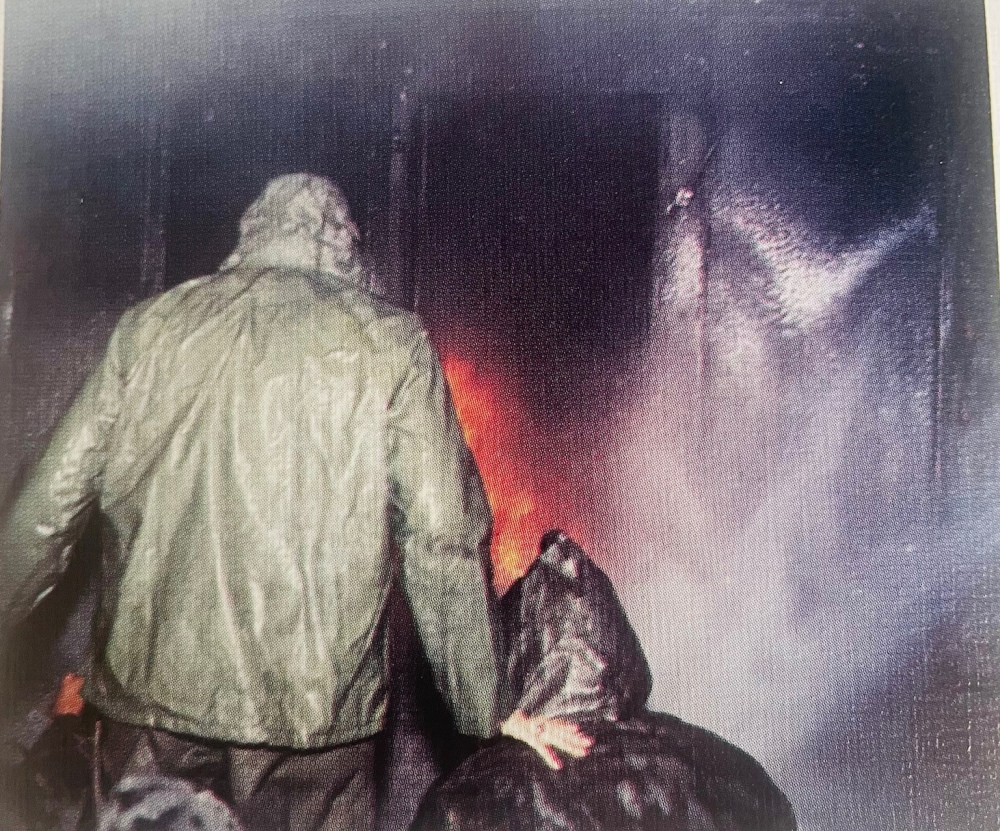

One of my favorite memories of boot camp was the firefighting trainer. That was a big day for a young crew since we had done nothing but classroom training and watched films up to that point. At Great Lakes, you got a chance to fight an actual fire in a confined space with real smoke. It was a hot summer day, and we had the minimal amount of protective gear. I think they gave us gloves and a weatherproof jacket, but not much more than that. This was long before the advanced gear that sailors wear now. And we had no exotic equipment like infrared or even Airpacks like those that are common for fire departments. We did have old fashioned OBA’s (Oxygen Breathing Apparatus’s) that had an oxygen candle which once ignited gave you about an hour of oxygen. But most of the time, we just made it a point to not breath too deeply.

The evolution was pretty heavily monitored but they wanted you to have the most realistic experience you could imagine. The year was 1972 and there had been a number of really bad shipboard fires in the previous decade. The infamous fire on the USS Forrestall was fresh on everyone’s mind and the training included actual film from the casualty. While the heat from the fire brings its own danger, the ensuing smoke added to the chaos since it was thick and black and made vision nearly impossible. Getting separated from the team in the bowels of a ship was a sure-fire way to cost lives.

In the classroom, we got to see old fashioned movies that captured fires on board ships. Even though the movies were old, the state-of-the-art equipment was pretty cool. The navy was using closed circuit tv equipment and it was impressive to see at the time. You have to remember that when my generation was growing up, we progressed from having a black and white tv to color. Plus, the channels were pretty limited. No cable until later. The films were supposed to teach you how to attack a fire and what actions would knock it down quickly. The emphasis was on doing so in a way that would bring all of the firefighters back to safety once the casualty was over. The instructors were no nonsense old salts that emphasized the life and death aspects of fires on board ships. Some had some pretty gruesome stories to relay to our group of young recruits. The part that sticks in my mind was that quite often sailors didn’t die right away from burns. Depending on the severity of the burns, a long painful recovery might be the result of getting caught in a burning compartment. Needless to say, I thought about that for many years afterward when the submarine or ship had a fire on board.

Fire in the paint locker

We learned about the fire triangle which are the elements needed for a fire to exist. Fuel, heat and oxygen. The goal in firefighting is to eliminate any one of the three sides to make the fire stop. Then we learned about the kinds of fire you might see called general classes of fire. Class A fires were normal combustibles such as mattresses, dunnage, rope and canvas (along with other materials). These are best extinguished by the cooling effect of streaming water or water spray.

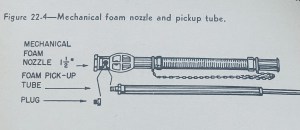

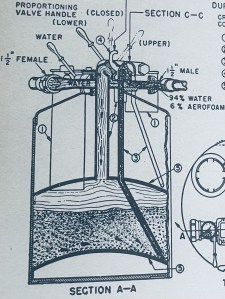

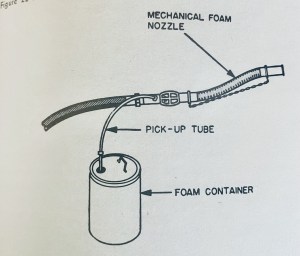

Class B fires are those that involved inflammable liquids such as gasoline, oil, grease, paint, and turpentine. These fires burn at the surface where the vapors burn off. A smothering or blanketing of the burning liquid is best for putting the fires out. The method in use was to use foam, CO2, dry chemical, steam and combination use of fog and foam. The foam we used in boot camp and later on board ships was AFFF (Aqueous Film Forming Foam).

A Frothy Mixture

AFFF was a type of firefighting foam that was first developed in the 1960s by the U.S. Navy. It was designed to quickly extinguish flammable liquid fires, especially fuel fires. AFFF works by forming an aqueous film that spreads across the surface of hydrocarbon fuels that prevents them from reigniting.

Modern AFFF formulations also contained fluorinated surfactants such as perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). These chemicals give AFFF its fire-extinguishing properties. However, PFOS, PFOA, and related per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are also linked to serious health effects in humans and animals.

I am relatively sure that our instructors were not aware of the dangers of AFFF at the time. Since they spent an inordinate amount of time trying to scare the shit out of us before our firefighting days. I am certain they would have remembered to add that little bit into their lectures. The description in the Bluejackets manual called it a “frothy mixture” of water and chemicals. The foam had the property of just sticking better to a flaming area than water which is subject to the motion of the ship as it floats in the water and CO2 which blows away in open spaces. The only caution we were given about using foam was that since it does stick to things it is generally not used on Class C electrical fires or Class A (wood, cloth, etc.) fires. But we were assured that a little foam will do the work of a lot more water, but the mess it makes makes it a last resort – except for large Class B fires when it is an absolute must.

The Big Day

Part of our training would be a class B fire where a vessel filled with oil would be set ablaze. We got to use the foam and the wands just to see the difference. I remember walking through the foam and being unhappy that my BoonDockers would be trashed out.

One of the pictures I saved for the last half century was what I looked like at the end of the day. I am reminded that the way we washed clothes back in the day was at a wash sink next to the head. I don’t remember ow hard it was to get the chemical and smoke smell out of the uniform I wore that day. I guess some memories are just not worth keeping.

After boot camp, I began my journey to become a submariner. We relearned damage control techniques that were unique to submarines. But “learning to see” was even more of a skill. When the lights go out in a submarine for any reason, it is incredibly dark. I was only involved with a few minor fires over the years. Mostly galley fires. But we drilled like our lives depended on it. We also had emergency air breathing masks with hookups scattered throughout the boat. But knowing the location of all of those hookups in the dark was just another way we learned to carefully map out every lifesaving device. But I don’t remember any AFFF on boats.

Sometimes, though, things are hidden from your eyes.

https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/pfas.asp

PFAS – Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals found in many products, such as clothing, carpets, fabrics for furniture, adhesives, paper packaging for food, and heat-resistant/non-stick cookware. They are also present in fire-fighting foams (or aqueous film forming foam; AFFF) used by both civilian and military firefighters. Also known as the “forever chemicals”, PFAS are persistent (i.e., they do not break down) in the environment, and since they are used in the manufacturing of so many products, they are widespread internationally.

Exposure to PFAS During Military Service

In the 1970s, the Department of Defense began using AFFF to fight fuel fires. The release of these chemicals into the environment during training and emergency responses is a major source of PFAS contamination of ground water on military bases.

Concerns have recently been raised from communities surrounding bases about whether PFAS-contaminated ground water on military bases may be affecting off-base water supplies. The Department of Defense (DOD) is currently conducting an investigation into the extent of PFAS contamination on its bases and is taking several actions to protect against future exposure.

According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ASTDR), some studies in humans suggest that certain PFAS may be associated with:

- Fertility issues and pregnancy-induced hypertension/preeclampsia

- Increased cholesterol

- Changes in the immune system

- Increased risk of certain cancers (e.g., testicular and kidney cancer)

- Changes in fetal and child development

- Liver damage

- Increased risk of thyroid disease

- Increased risk of asthma

Compensation benefits for health problems

Currently, there are no presumptions related to PFAS exposure in the military. However, Veterans may file a claim for disability compensation for health problems they believe are related to exposure to chemicals during military service. VA decides these claims on a case-by-case basis. There is a link at the bottom of the VA page above.

I truly am proud of my service to my country. I would do it again without hesitation.

But a lot more work needs to be done to determine if the products we use to defend her have long term unintended consequences.

It would be fair if the makers of those goods truly learned how to see before they put another generation in harm’s way.

Mister Mac

Bob, as always, your posts are right on point. All of us that served 40 plus years ago have similar memories of fire fighting training in bootcamp. I have a vivid one of us taking what seemed like forever to put out a pool sized trough of fuel with a firehose only to have the instructor reignite it with a single stroke of a welding torch flint. Then we put it out again with AFFF. The instructor then asked if anyone wanted to stand in the trough. There were no takers, so he said “ok, then I will”, and proceeded to walk out to the middle and hit it with about a dozen strikes from the flint. It did not reignite. “This is why you want AFFF on a fuel fire”.

As much as that instilled a great respect for Navy Instructors (in fact, I had three tours as one myself), I also have memories that should raise an eyebrow. As an IC-man on a submarine I was very accustomed to having a healthy concern for our atmosphere. I was a CAMS tech, and frequently used various portable monitoring devices such as Draeger gas tubes. But as we went into the shipyard for overhaul, I was sent to school to become a “Gas Free Engineer” because spaces have to be certified to be safe to work in. Every other student in my class was from the surface fleet, so most of them did not have as much of a background as I already did. One day they brought in a gas cylinder of R-12 (freon) so we could get hands on experience with the “sniffer” used to detect leaks. At one point one of the instructors said “hey, watch this” (which is the equivalent of saying “hold my beer”), and opened the cylinder and lit the gas on fire. “Isn’t that a pretty green” he said. I lost my mind and flew out of my chair and yelled at the top of my lungs “everyone OUT of this class room RIGHT #&@king NOW!!!” Once I had everyone out (no, I didn’t have authority as a student, but thankfully everyone accepted my tone of voice as reason enough) I turned my attention to the instructor. “You stupid $^%&@#$@#, you’re making PHOSGENE gas”.

How much better the world would be if we all adhered to the axiom of “You have a responsibility to yourself, a responsibility to your shipmates, a responsibility to the Navy, a responsibility to your loved ones… but it all starts with the responsibility to yourself”.

ICFTBMT1(SS) Maxey, USN (retired)

Thanks for a great response to the post. I find that some of my memories are coming back stronger now that I have reached my seventh decade. Your post is a solid reminder that it actually happened.

Mac