Homecoming 1946

Nearly eight million men and women served in the United States Armed Forces during the second world war. Many recent articles in various news outlets and television stories highlight the hundred plus years the few remaining survivors are celebrating this year. But the numbers are diminished greatly with the passing of time. They were called the Greatest Generation since so many of them were responsible for pushing back the dark forces of totalitarianism.

My dad was one of them as was my grandfather from my mom’s side. Selfless patriots that raised their hands in times of trouble and quietly went about the business of serving the nation. I watched him proudly march down the streets of my hometown every year until I finally joined myself. It seemed like the right thing to do and I do not regret the sacrifices all of us were called upon to make.

My dad entered the war in March of 1945 and was later stationed in the Philippines. His role was to help prepare the supplies needed to support the planned invasion of Japan. Of course, the use of atomic bombs helped to bring the war to an end and then the entire focus changed. One of the changes was that we had no need for so many men and women to be overseas so a method to bring them home as quickly as possible needed to be developed.

Operation Magic Carpet

Operation Magic Carpet was the post–World War II operation by the U.S. War Shipping Administration (WSA) to repatriate over eight million American military personnel from the European (ETO), Pacific, and Asian theaters. Hundreds of Liberty ships, Victory ships, and troop transports began repatriating soldiers from Europe to the United States in June 1945. Beginning in October 1945, over 370 United States Navy ships were used for repatriation duties in the Pacific. Warships, such as aircraft carriers, battleships, hospital ships, and large numbers of assault transports, were used. The European phase of Operation Magic Carpet concluded in February 1946; the Pacific phase continued until September 1946.

Since dad had entered the war in March of 1945 and did not see combat, his ride home would have to wait. There was a point system developed that prioritized who would get to go home first. Dad did not get to come home until September of 1946. Back home, labor conditions were deteriorating. The war was over, but the labor movement was trying to level up the pay and benefits that they had held steady during the war.

From the book I wrote about my dad’s service called “Love, You Son Butch”:

On January 20th 800,000 steelworkers of the CIO walked out in the largest single action in America’s history. Of that number, 227,000 were in the Pittsburgh District and picket lines soon appeared at the Irwin works and National Tube Works where John’s father was a foreman. The strike occurred despite President Truman’s attempts to forestall them by conducting a fact finding effort. By the next day, all of the mills in the area were silent for the first time and production levels hit a fifty year low. Phillip Murray, in a national broadcast accused the steel companies of “an evil conspiracy” to destroy labor unions.

Phillip Murray was an emigrant from Scotland who rose from being a coal miner to head of the United Steel Workers of America Union. Prior to the war, he had also risen to the top of the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) replacing the infamous John L. Lewis. As the head of the unions, he had supported Franklin Roosevelt during the war, but spearheaded efforts to advance the cause of his members against the companies they worked for. During his term of office, the USWA grew to over 2500 local unions including steel and aluminum workers. He died in San Francisco in 1952.

Wed. Jan 23, 46

Dear Mom – Pop,

Well, How’s the good people today? I got four letters today, one from Kreta, one from Ixxy, one from Mom and one from Pop dated the Jan 16 and Jan 14. I’m writing to you pretty often but I recon the mail is tied up some place. There has been two barges of mail burn up that is mail coming to us but it wouldn’t affect your mail any. I mean mine going to you. You never got any registered letters yet? Well its funny to me, I mailed them on the 20th of December, I think or around there. Nobody out here understands the strikes at home. Boy, I’d be glad to work for those wages to be back there. It seems to me that old Truman isn’t doing such a hot job of things and neither does anyone else think so here.

You know I could write one month and a month later write the same thing. When censorship was on everybody said wait until its off. Now its off, it doesn’t make much difference. I don’t think I ever told you what our sacks are like. Well, there made of two x fours with a cot on the top and a cot on the bottom. They are very comfortable (ha-ha) Joe, every time he moves above me I move too. So you can see that we yell at each other quite a lot. You know I am beginning to miss milk. Boy it would really taste good right now. We have milk and ice cream but its all powdered mixed with water and frozen then fixt to eat. Its alright but not as good as the real thing.

Thursday: I started this yesterday but as you can see I didn’t finish it till today. I went to the movies last night. I saw “Ding Dong Williams” It wasn’t so good. Its raining right now in fact it rained a good bit this last couple days. Burkhart has a truck tonight. I’m gonna go with him I think, I haven’t as yet made up my mind. Gee Mom, I’m happy to hear your blood pressure is a lot lower. I only hope you stay that way. Well, Mom-Pops, I recon I’ll sign off for the morning.

God be with you always

Love, Your Son

Butch

While my dad’s homecoming was delayed, not everyone got to have a homecoming.

The casualty lists were not released in full until months after the war was over. This would include a final tally of ships and submarines lost during the conflict. While many newspaper articles hinted at the losses, it was only after the enemy was defeated that the actual scope was revealed. Even though many families got telegrams from the war or navy departments, some families would just have to wait for a final message. One of those families was the Bush family of Long Island City, NY. From the Windham County observer (Putnam, Conn.), January 23, 1946:

James W. “Jimmy” Bush, Jr., Once Junior Counselor On Staff at Camp Woodstock Now Officially Listed by Navy as Dead

Hero Son Of Putnam Area Residents Was Volunteer Crew Member Aboard Famed U. S. Submarine Grayling In Pacific Combat Waters When Craft Disappeared Without Vestige Of Clues Ever Developing As To Fate Of It, Or Trace Of Survivors—Had Been Classed As Missing In Action Since Oct 19,1943 — Victim Cited By Divisional Fleet Commander.

Motor Machinist Mate James W. “Jimsy” Bush, Jr., once a junior counselor on the staff at Camp Woodstock subsequent to his having passed several of his ’teen years as one of the enrolled campers at the regional “Y” summer recreational and educational resort on the shores of Black Pond, must be presumed dead, as of Jan. 3, 1946, according to Naval notification just received by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. James W. Bush, Sr., of Long Island City, N. Y., who for many years have maintained a summer home in Union East-District, close to the West Woodstock boundary line. Since infancy days “Jimsy” had been accustomed to spend his vacations and summers at the Union East District summer home of his parents. His was the first gold star name affixed to the “Union Honor Roll.”

“Jimsy” had been listed as missing in action by the Navy since Oct. 15. 1943, when the faced U.S. Submarine Grayling, aboard which he was serving as a volunteer crew member on this particular mission against Jap shipping in Pacific waters, was reported as long overdue and presumably lost.

No clues or vestige of official data ever was obtained as to the fate of the craft, or as to whether there were any survivors. Absence of any definite clues had caused relatives to hope that the war’s end might develop some clues among official Jap records, or that a survivor of the Grayling might be discovered in some Nip prison camp. The official “presumed dead” notification received by his parents last week is accepted generally as finally closing the chapter recording the war heroism of the Camp Woodstock alumni, and youth accepted as one of the Putnam areas’ own.

The submarine last was heard from proceeding from the south west Pacific toward Pearl Harbor from an offensive war patrol in heavily-pa trolled enemy controlled waters. Not a vestige ever was received in either rumor or report as to her fate, or as to whether there were survivors.

There also is no information available as to any successful attacks made during this last patrol. However, since the Grayling had achieved a distinguished record since the early days of the war until the time of disappearance by relentless and aggressive attacks against the enemy, it is assumed the craft was executing just such bold tactics up until the time she was declared missing.

It was on the Submarine Grayling that Admiral Nimitz hoisted his flag when he took command of the fleet nearly four years ago.

“As motor machinist’s mate of the submarine.” the commander of his division wrote, “James Bush, Jr.’s performance of duty materially contributed to the success of the vessel against the enemy. The commander forwards this commendation in recognition of his splendid performance of duty, which was in keeping with the highest traditions of the Naval service.”

In recognition of his performance of duty and operations against the enemy, he was awarded the submarine combat insignia with three stars and a citation in absentia.

He also received a citation on the SS Trinidad before being assigned to the Grayling.

Both his parents made distinguished service records in various branches of the combat forces during World War I.

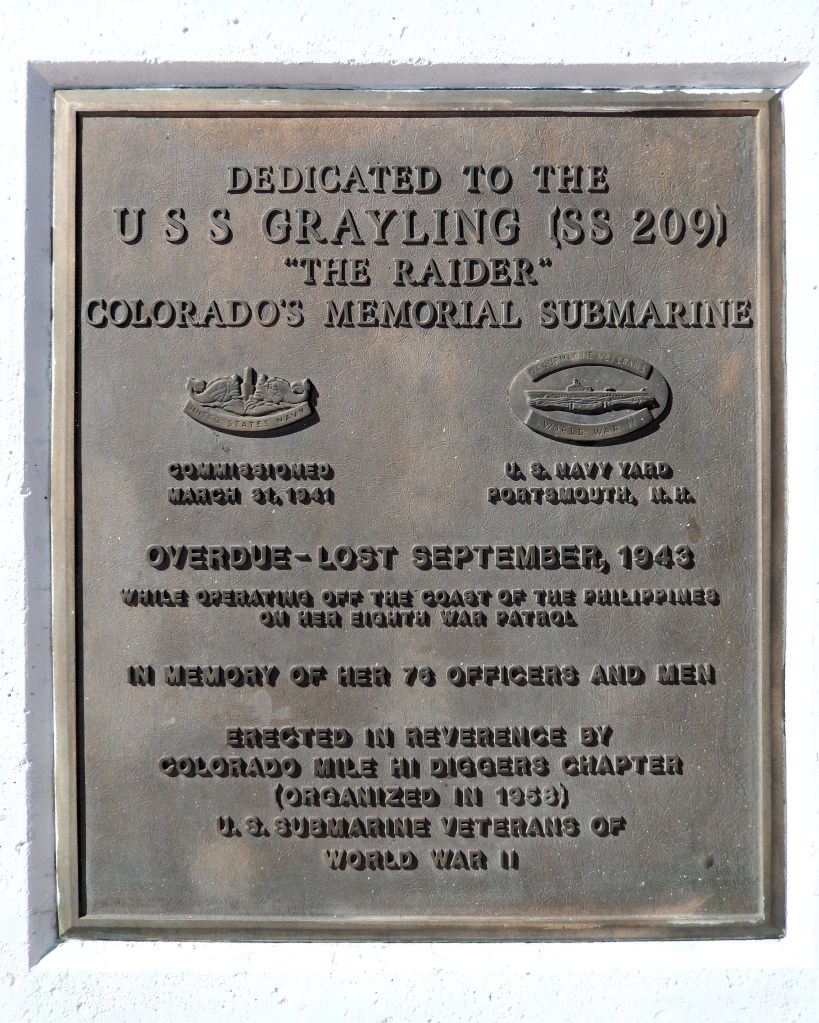

USS Grayling SS 209

USS Grayling (SS-209) was the tenth Tambor-class submarine to be commissioned in the United States Navy in the years leading up to the country’s December 1941 entry into World War II. She was the fourth ship of the United States Navy to be named for the grayling. Her wartime service was in the Pacific Ocean. She completed seven war patrols in the following 20 months, and is credited with the sinking of over 20,000 tons of Japanese merchant shipping and warships. Grayling received six battle stars for her World War II service. She was declared lost with all hands in September 1943. Her fate remains an unsolved mystery. Of the twelve Tambor-class submarines, only five survived the war.

Grayling sailed for Pearl Harbor on 17 December, arrived 24 December, and had the honor of being chosen for the Pacific Fleet change of command ceremony on 31 December 1941. The ceremony would normally have taken place on a battleship, but all the fleet’s battleships had been either sunk or damaged during the Japanese Navy’s attack three weeks earlier. On that day, Admiral Chester Nimitz hoisted his flag aboard Grayling as Commander, Pacific Fleet and began the United States Navy’s long fighting road back to victory in the Pacific.

Grayling began her eighth and last war patrol in July, 1943, from Fremantle. She made two visits to the coast of the Philippines, delivering supplies and equipment to guerrillas at Pucio Point, Pandan Bay, Panay, 31 July and 23 August 1943. Cruising in the Philippines area, Grayling recorded her last kill, the passenger-cargo Meizan Maru on 27 August in the Tablas Strait, but was not heard from again after 9 September. She was scheduled to make a radio report on 12 September, which she did not, and all attempts to contact her failed. Grayling was officially reported “lost with all hands” 30 September 1943.

On 27 August 1943, Japanese ships witnessed a torpedo attack, and the next day a surfaced submarine was seen, both in the Tablas Strait area, and then on 9 September a surfaced American submarine was seen inside Lingayen Gulf. All of these sightings correspond with Grayling’s orders to patrol the approaches to Manila. On 9 September 1943, Japanese passenger-cargo vessel Hokuan Maru reported a submarine in shallow water west of Luzon. The ship made a run over the area and “noted an impact with a submerged object”. No additional data are available.

Assuming she survived this incident, no other recorded Japanese attacks could have sunk Grayling. Her loss may have been operational or by an unrecorded attack. The only certainty, therefore, is that Grayling was lost between 9 September and 12 September 1943 either in Lingayen Gulf or along the approaches to Manila. ComTaskFor71 requested a transmission from Grayling on 12 September, but did not receive one.

Grayling was credited with five major kills, totaling 20,575 tons. All but the first of Grayling’s eight war patrols were declared “successful”.

The boat, which took 76 crewmembers to the bottom with her, received six battle stars for her service.

Memorials

Her entire crew of 76 plus rescued MSgt Roy W. Wilfon were lost when Grayling went missing. Each earned the Purple Heart, posthumously. The U.S. Navy crew were officially declared dead on January 3, 1946. Wilfon was officially declared dead August 31 1943. All are memorialized at Manila American Cemetery on the tablets of the missing.

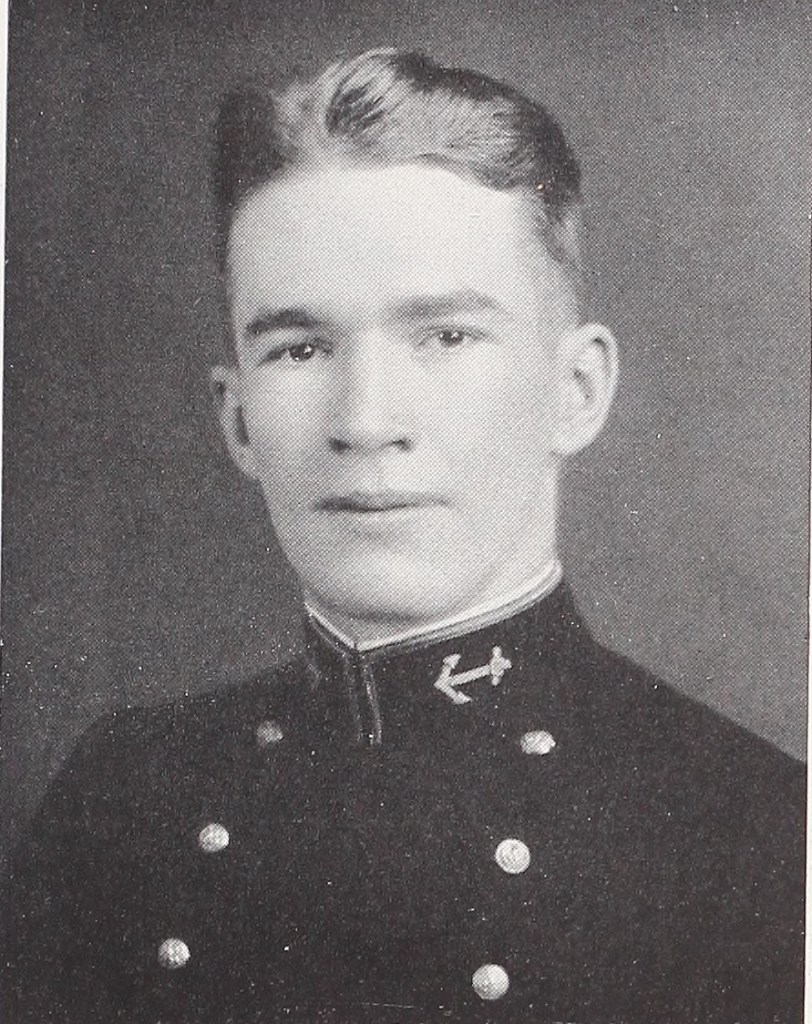

LCDR ROBERT MARION BRINKER

Park Ridge, Illinois

“Bob” “Bunker” “Hans”

Bob was lost when USS Grayling (SS 209) was sunk sometime between September 9-12, 1943. He was the boat’s commanding officer.

Robert graduated from Maine Township High school in 1927. “Bob” Here’s our great future architectural engineer. When he’s famous people will say, “It’s because he ate ‘Copperats’ and threw ‘snowballs’ when he was young.” Band 3, 4 (baritone horn.)

He attended the University of Illinois for two years and was a member of the fraternity Triangle.

On March 28, 1940, Robert and his wife Margaret sailed on the S. S. President Taft from Manila to San Francisco. Their address was c/o Electric Boat Co., Groton, Connecticut. On July 11, 1941, Margaret and daughter Lorna, age 9 months, sailed on the S. S. Mariposa from San Francisco to Honolulu.

In the fall of 1942, Robert’s submarine sank 21 Japanese ships before returning to American waters.

In July 1944, the Park Ridge group of the Women’s Defense Corps of America was named the Robert Brinker chapter.

He was survived by his wife and 3-year-old daughter Lorna. His wife, the former Margaret Lucille Stonebrook, died on April 6, 1950, in San Francisco.

His father was Marion, mother Lorna, sister Alice (Mrs. Hall Teeman,) and brother Sidney who was an Ensign in the Mediterranean area.

All told, 52 American submarines were listed as still on patrol at the end of the war.

The mastery of the atom in 1945 opened up an entirely new realm of possibilities for submarines. Post war analysis showed that the high cost of submarines related to operational weaknesses could not be sustained in future conflicts. The submarine community played a key role in pushing back the Japanese threat but at an extremely high cost.

If submarines were to be a part of the future of naval warfare, something had to change. The question of inclusion of a nuclear reactor was that opportunity. Even in January of 1946 as families were being given final closure on the loss of the sons, the idea was beginning to take hold.

1946 would be a pivotal year in seeing the atom harnessed in ways that even Jules Verne could not imagine.

But for now, saying goodbye to loved ones who would never be coming home was the order of the day.

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidd’st the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

Lord God, our power evermore,

Whose arm doth reach the ocean floor,

Dive with our men beneath the sea;

Traverse the depths protectively.

O hear us when we pray, and keep

Them safe from peril in the deep