Chapter Twelve

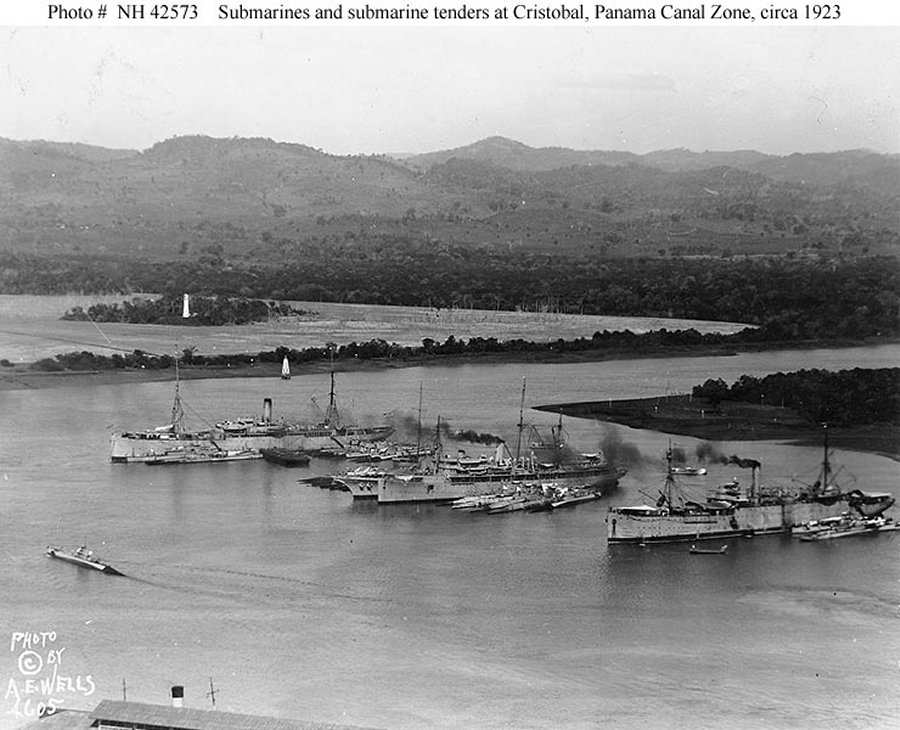

Pig Boats at the Panama Canal

From the Annual Report of the Navy Department (1921/22), an accurate description of life on board any of the submarines of the day:

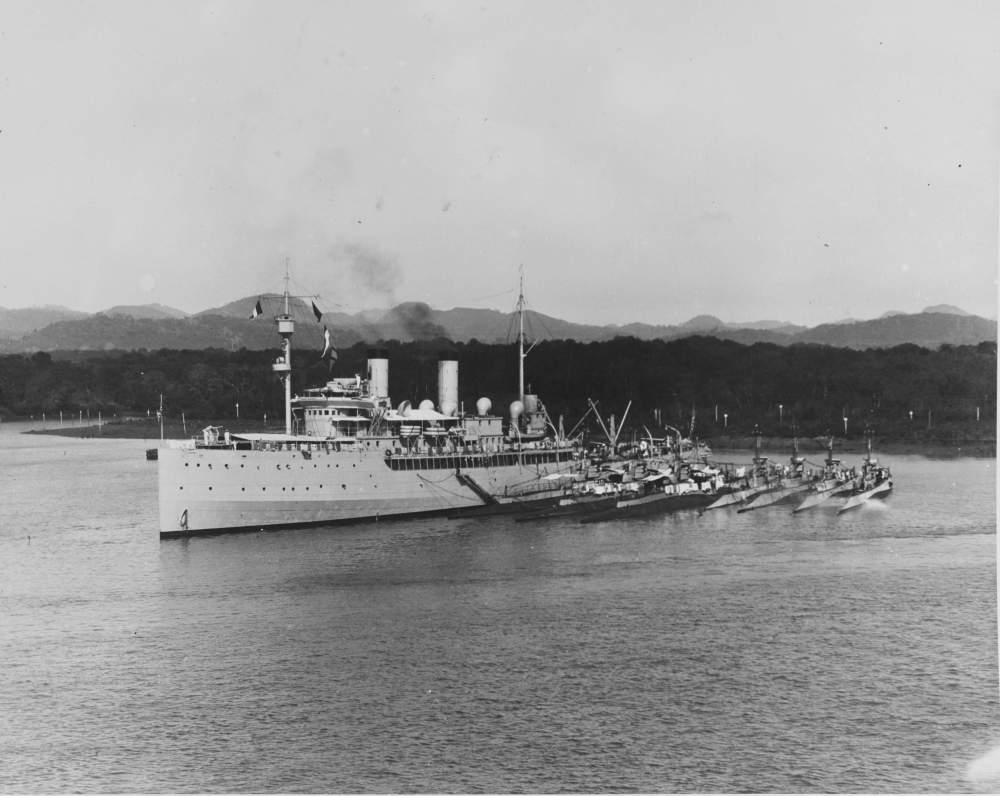

“Submarines, from their size and peculiarities of construction and operation, are far less habitable than the usual types of surface craft. They do not afford room for exercise in fresh air, and do not have room for the sick quarters, supply departmental activities, machine shops, offices, and similar installations that surface vessels have for their current up keep. They must depend for these things on something outside themselves, and this need is net by tenders and bases. The ideal arrangement is to provide a sufficient number of tenders, merchant type vessels, which can provide living quarters and upkeep facilities for from 4 to 10 submarines and go with them to any place where their services may be needed and operate there for long periods of time.

The expense in men and ships of enough mobile tenders to provide for the entire submarine force would be too great, and the deficiency is met by submarine bases, or shore based submarine tenders, which have been established at New London, Hampton Roads, Coco Solo, San Pedro, and Hawaii. (Editor’s note: Cassin Young would serve in one position or another at every one of these locations except Hampton Roads).These bases furnish living quarters, sick accommodations, machine shops, electricity, compressed air, water, et., to the submarines that are attached to them precisely as do the mobile tenders to the submarines that they tend. They also serve as fitting out yards for new submarines.”

Life on board the submarines in the Canal Zone involved a number of activities supporting their key role as security patrols. The crew of the R-22 was relatively new since the boat had only been completed. The entire crew was made up of sixteen enlisted men, and three officers. In the 1920 census, the Captain, two officers (including Young) and one Chief Petty officer are listed as having wives present in the zone. The crew itself represented all regions of America and two of the men were born in places as far away as Ireland and Poland. All had to have graduated from submarine school to become part of the R 22 and by all accounts the ship kept a good record while on assignment.

One of the interesting events that happened shortly after she arrived with her squadron mates was something that was not part of the original tasking for the boats. Shortly after the squadron arrived in January 1920, the American Shipping Board steamship, the S.S. Marne had an onboard explosion causing a fire that threatened the ship. According to an article in the Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), 27 Jan. 1920, the steamer was towed by tugs to the outer harbor when the fire got out of control. With her decks awash, she soon was the target of the submarines from the nearby base. The boats poured fifty four three inch shells from their deck guns into the hapless vessel causing her to sink. She settled in thirty feet of water and was considered a total loss. The vessel had sailed from New York and was carrying an 8,000 ton cargo of general merchandise on its way to Melbourne. This was a very unusual tasking for the small submarine squadron and probably caused quite a ruckus among the crews involved.

In February and March, the Canal Company attempted to raise the Marne but each time she was raised the fires from the cargo hold reignited. She sank twice more before she was finally brought to the surface and her cargo was removed. The cargo was a combination of gasoline, benzene and turpentine. There were not enough stevedores available (or willing) to off load the dangerous cargo but it was noted at the time that even when it was in a sunken condition, containers of the volatile fluids continued to break free from the cargo hold and threaten both shipping and the submarine base. Contemporary reports nor official Navy reports are scarce on details of which submarines were involved with the attempts to sink the Marne. It is possible to surmise that the officers of the boats involved would have been topside while the guns were in use. If that were true and Young’s boat were involved, it would be the one of many times he manned a three inch gun. His actions would be mirrored on a fateful day on another ship in a place called Pearl Harbor that would forever change his life.

Life in the Canal Zone was not without its notoriety. There was a massive strike by black workers in the Panama Canal Zone on February 24, 1920. A strike was called by the United Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way and Railway Shop Employees. These laborers in Panama represented the long held beliefs of unfair treatment of workers in the zone who had done much to create this waterway for the world. Fifteen thousand men walked off the job in an effort to convince the company to raise their pay and improve their working conditions. The result was a work stoppage that would have impacted the families who depended on the transportation system for travel and goods.

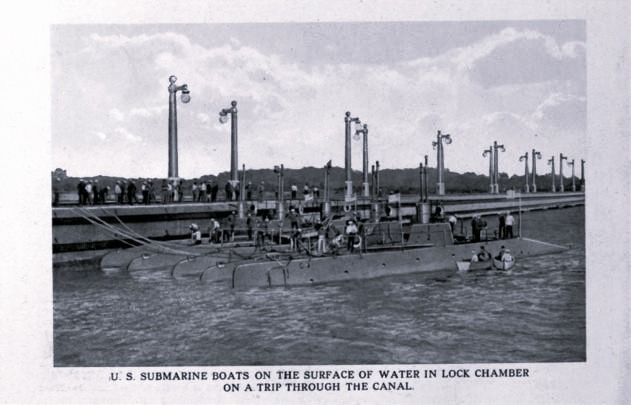

It probably did not help the submarine families at Coco Solo that all seven of the R Type submarines were sent through the canal to the Balboa side on the exact week that the strike was called. After the harrowing journey they were placed into drydock for hull cleaning and some repair work that was needed to maintain the boats in top condition.

The strike was settled by March the second but services provided by the railroad were curtailed and probably stretched the patience and resources of the families and the men. The Governor of the Canal, Chester Harding put a good face on the aftermath but it did sent a signal to all that were concerned that an extended labor stoppage would have real consequences.

The canal was still new enough that it garnered international attention. Visits by Japan’s and Europeans military and commercial ships were frequent in those days and the Canal Record dutifully noted the passage of each commodity and each ship. Even though it had been opened for a number of years, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the official opening of the Panama Canal on July 12, 1920, after forty-two challenging years of trying to link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

By the President of the United States

A Proclamation

“Whereas section 4 of the act of Congress entitled “An act to provide for the opening, maintenance, protection, and operation of “The Panama Canal,” approved August 24, 1912 (37 Stat. L. 561) and known as the Panama Canal act, provides that upon the completion of the Panama Canal the President shall cause it to be officially and formally opened for use and operation; and

Whereas the canal is now completed and is open for commerce:

Now, therefore, I, Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States of America, acting under the authority of the Panama Canal Act, do hereby declare and proclaim the official and formal opening of the Panama Canal for use and conformity with the laws of the United States.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done in the District of Columbia this 12th day of July, in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and twenty, and of the independence of the United States of America the one hundred and forty-fifth.”

Woodrow Wilson

By the President:

Norman H. Davis

Acting Secretary of State

During July of 1920, the designation of USS R-22 was changed from “Submarine Number 99” to “SS-99.”

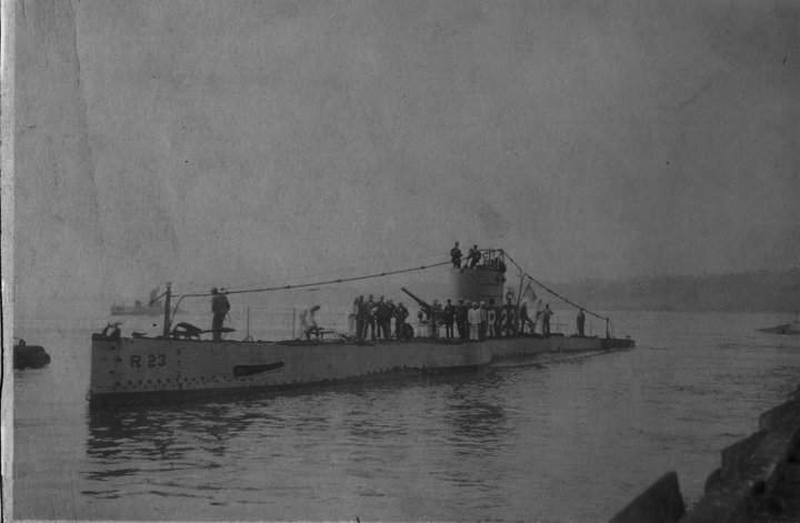

In September of 1920, Lieutenant Cassin Young would achieve the next milestone in his career as he took command of the submarine USS R-23, now known as the SS-100, one of the other seven R boats in the Canal Zone.

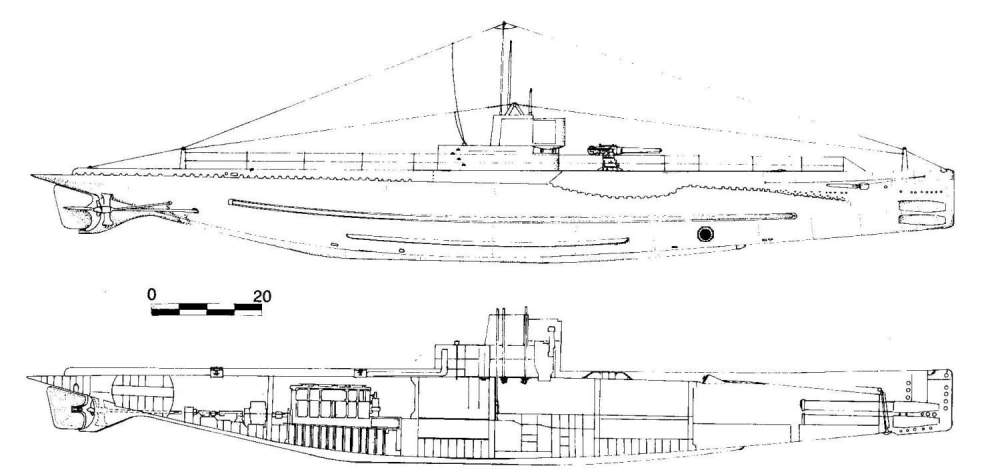

The three officers on board shared a small space in what was known as the forward battery area.

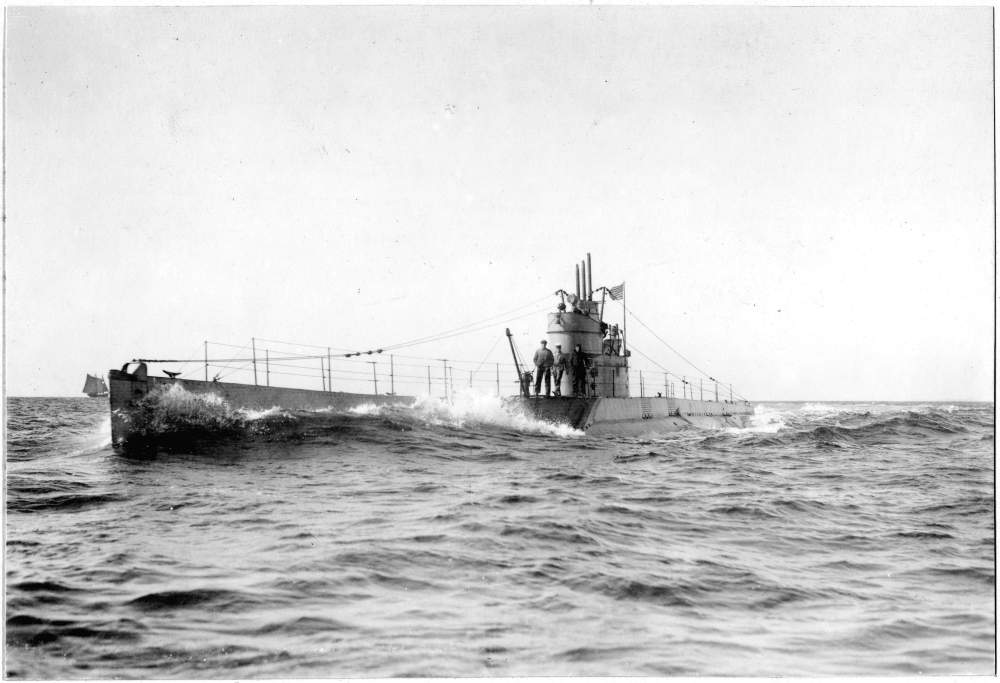

The bunks were small and all of the equipment on the boats was designed to make maximum efficiency of the space available. The boat captain would have to rely on his experience, training and sea knowledge to keep his craft safe from all of the inherent dangers that lurked both outside and inside the hull of the submarine. The boats were an improvement over the earliest Holland class and sat higher in the water, but the dangers of operating in an area as densely populated as the entrance to the Panama Canal would have been a daily issue. Surface radar in that age was non-existent and even if it was, the little boats would not have stood out very much from the surrounding hills and obstacles. A Skipper had to keep a watchful eye every day his ship was operating submerged and each night they were on the surface.

In the States, things were undergoing some massive changes too. The progressive Wilson era was about to come to a close and Warren G. Harding, the surprise candidate from the Republican easily made his way into the fall elections riding a wave of optimism. His dream of leading the world as a leading member of the League of Nations was dashed on the rocks of a reluctant Congress and American people. The reasons for that reluctance are many but some of the ones that mattered most to the people were the memory of the entangling alliances that had led to the last global conflict. The fear of being drawn into someone else’s peacekeeping army or navy seemed out of step with a country isolated from the old failing monarchies of Europe. Truthfully, the country was probably just ready for a change from the Wilson years and Harding provided the pathway to the future.

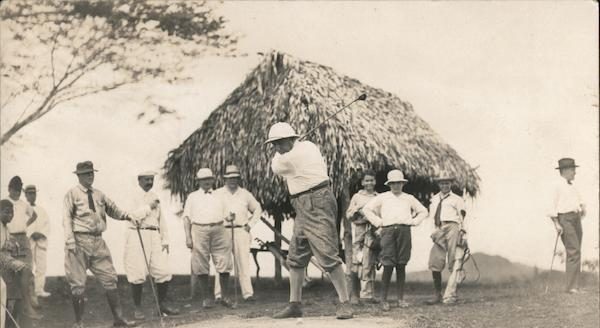

After his successful election, Harding and his entourage made a southern trip that included sailing through the Panama Canal. In an article published by the Evening Star. (Washington, D.C.), 27 Nov. 1920, the president elect ended his tour with a visit to the zone with a visit to the fortifications and submarine base of the eastern side. He took the opportunity to play a round of golf at the local course, swim in the salt water pool and enjoy the food and entertainment of the country after visiting with local officials. His ship set sail for Jamaica on its way back to Washington and the time period which would come to be known as the Roaring Twenties.

The submarine fleet settled back down into its routine.

The Navy was learning a lot of lessons about the boats that would influence future design and have a serious impact on submarine warfare. One of the most important lessons had to do with the modern engineering principles of air conditioning. All of the American boats had been built for cold water service and the semi-permanent stationing of boats both in the Canal Zone and the Far East revealed some of the mechanical and habitability issues that came with operating in tropical zones.

The quality of the air inside any submarine is affected by a number of factors. The machines that operated the boat emitted carbon and oil into the atmosphere which combined with the moisture led to serious issues with equipment efficiency. The R boats could operate for about two weeks at a time under these circumstances before they would need a two week maintenance period. The boats were initially not designed to replace the air frequently enough and even when they were upgraded, it was obvious that they reverse affect was felt. More humid air increased the breakdowns.

People affect the quality of air as well. Breathing depletes the oxygen level in the ambient air. Every man on board consumes about one standard cubic feet of oxygen per hour while simultaneously producing a large amount of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. The machines add their own waste air products as do cooking and other activities typical in the early days of submarines like smoking. The R-boats had been built for coastal patrols and the length of time submerged was designed to support frequent trips to the surface.

The last part of air conditioning that impacts any boat operations is the inability of the early boats to dehumidify or cool the air. During the warmer seasons and operating on the surface, the boats were like magnets for the heat of the atmosphere and the inside of the boat felt like the inside of an oven when it was running both main engines and other equipment.

The result of the lower efficiencies in air conditioning was a reduction of time that could spent patrolling. These lessons were not lost on naval engineers as they added more and more artificial methods to condition the air on the little boats while looking towards the future when actual fleet boats could be built. The suffering of the Panama based crews led the way to improvements that would pay off for future generations.

When Cassin would return to his home base with the submarine, his wife would experience the one thing that all submarine wives have experienced from the beginning of the time when men sailed on these diesel engine boats. The smell. Even for a short period of time, all of the clothing the men would wear became permeated with a foul mixture of diesel fuel, sweat, cooking residuals and the additional smells that came from living inside of a tube that is closed on both ends. Having the availability of a laundress would have been more than a satisfied luxury for the submariners wives… it would have been an absolute necessity. While some submariners may have balked at the term Pig Boats, it is easy to understand why they were known as such.