Chapter Thirteen: While one Navy shrinks an enemy secretly grows

Between the years of 1920-1921, the United States was shedding the weight of the forces it had mustered to answer the call to action in the Great War. After the Wilsonian years and massive growth and investment, the Republican leadership clung to the new idea that the world was now safe for democracy and large navies were an expense the nation could live without. The Secretary of the Navy report of the same years showed that 376 vessels of every kind (including fourteen submarines) were placed out of service or never finished from the ambitious building programs of 1916 and the war. This drastic reduction was necessary because of the equally drastic reduction of men who were employed as officers and sailors. The world was fascinated with global peace and the United States was caught up in a wave of disarmament and peace seeking. Surely after the disastrous last war that cost the lives of millions and exhausted the world’s treasuries, no one would even think about another conflict.

Cassin Young and the Class of 1916 (as well as all classes since that time) had to be looking over their shoulders at the rapidly changing environment. In times of tighter budgets, opportunities for advancement also become tighter. All of the temporary wartime advances in rank were reversed in the early nineteen twenties bringing with it the loss of pay and advantages a career man had come to expect. Congress would discuss every single expenditure in the greatest detail over the coming years and even the need to replace ships and boats would become more political than strategic.

Panama probably seemed as safe a place as any for some of the officers and men. Far away from the eyes of official Washington, the Canal Zone had its own routines and customs and fell outside of the arms of one of the most constricting laws of its time: The Volstead Act. Prohibition had arrived in the United States just as the Young’s were sailing to Panama. The act was a long sought goal of many well-meaning people to prohibit the sale, transportation or use of any alcohol for consumption as a beverage. The actual consequences ended up creating an entirely new class of criminality. But in the Canal Zone, the law did not apply. Knowing sailors that was probably a welcome thing and may have even enhanced duty in the little far away port of Coco Solo.

The Young family’s stay in the Zone was coming to an end.

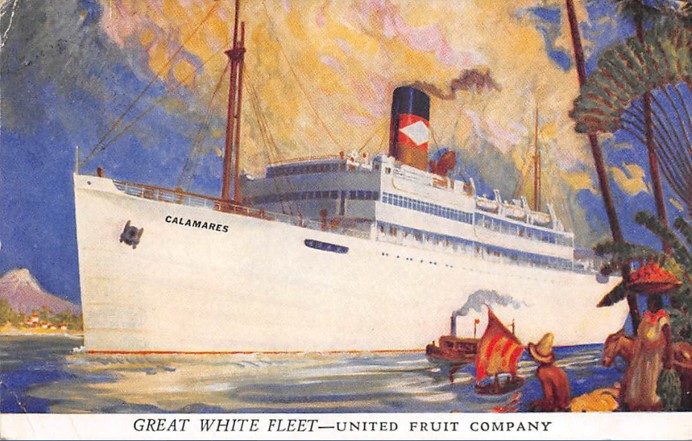

Less than a year after Charles was born, Cassin was ordered to leave Panama and sail back to New London to help fit out a new submarine, the S-51. This trip would be done as a family. They were assigned to travel on the SS Calamares, a United Fruit Company vessel that had served as a transport in the late war.

The United Fruit Company was rebuilding their steam ship fleet in the early nineteen twenties and had upgraded most of the “Great White Fleet” with more spacious cabins and amenities.

The family left for the states on June nineteenth and arrived in New York for the trip to Connecticut on July the tenth, 1921.

Slowing the growth of the world’s navies

While the ship was still sailing towards its destination, events in Washington began to occur that would shape the future of the Navy and the world as a whole. After many discussions with the British and others in the civilized world, Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes informed the British that the United States was ready to begin talks on arms limitations. The particular focus on these discussions would be on curtailing the size and capacity of the remaining global naval forces. To prepare for the naval conference, Assistant Secretary for the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt developed a list of five key points that he wanted the Navy’s General board to consider as a backdrop to our participation in the talks. This five points were:

- The United States will not consent to the limitation of its sovereign power

- The United States will continue to maintain the Monroe Doctrine

- The United States will not consent to any limitations of its Navy that might imperil any part of its territory or the citizens thereof.

- The United States must have at all times a sufficient force to insure unimpeded lanes of communication for its commerce.

- The United States must be in a position to maintain its policies and the rights of its citizens in any country where they may be jeopardized.

The board examined all of the policies of the nations invited to attend the conference. Their intent was to determine where the interests of those countries might be contrary to any of the five principles outlined or against any other outlying factors that could affect national security. In the end, the report included information about each country but specifically focused on Japan. The official view was that Japan’s foreign policies in regard to commerce and territory were definitely aligned towards eventual domination in the far eastern regions. Japan as a country was not large enough to provide for the welfare of all of its citizens and it lacked the raw materials needed for continued growth in a modern industrial era. The only way she could continue to meet her ambitious agenda was to obtain new territory and resources.

The General Board gave consideration to the institutional structure of modern-day Japan and determined that “Japanese governing classes [were] militaristic with feudal traditions; consequently, the Japanese Government [was] aggressive.”

The Board’s warning was taken into account when the Washington Naval Conference commenced in November 1921. There were a number of participants from nine nations that attended—the United States, Japan, China, France, Britain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Portugal. While the main consideration was limiting the growth of naval powers around the globe, the key drivers at this point were interests regarding the Pacific Ocean and East Asia. Soviet Russia was not invited to the conference. It had only been a few years since the revolution which helped to form the entity and the main powers were not ready to deal with them as a legitimate power yet.

The resulting treaty set boundaries on not only the size and scope of the world’s great navies, it also set in place prohibitive restrictions on bases and expansion in the far east. The goal for many was to try and maintain a tenuous balance of power between old colonial powers and the surging need for expansion by the Japanese.

The treaty itself is still studied as a model for arms limitations but is also in no small part responsible for many of the events that led up to the morning of December 7th, 1941.

The Navy General Board recognized that politically the winds of peace were blowing out any embers of the fires they had once ignited to warn the country of the need for preparedness. Stories from around the country were shared of loss and sacrifice in the Great War and the futility of future wars. The public was ready to spend their tax dollars on growth and opportunity and a large navy was expensive to build and maintain. The cost of maintaining the battleships alone was staggering and building bigger and faster models may have seemed important at one time but still drained the country of needed funds. The Naval treaty seemed like a winning proposition for all concerned and newspapers headlined the progress of the parties all through their negotiations.

The result for the Navy would be not just a loss of ships and equipment, but a shrinking force. Congress was quick to identify the potential savings from a smaller fleet and insisted that the Navy examine all of its rolls for excess people and make the need cuts. This would not be the first time or the last time the term “hollow Navy” would be appropriate. Ships would have to go to sea with minimal crews and growth in the new technologies such as air and subsurface would have to take their place in a long line of needs.

From the February 9, 1922 Washington Times newspaper:

NAVY STOPS WORK ON 14 GIANT CRAFT

Scrapping or Conversion to Merchant Ships in Store for 11 War Vessels.

In anticipation of ratification of the naval limitation treaty, which resulted from the Washington conference, and under which only three of the vessels involved will be completed as war craft, Secretary of the Navy Denby yesterday afternoon, under direction of President suspended construction work on fourteen capital ships under the treaty provisions.

The action of Secretary Denby after Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt had consulted with President Harding on the terms of the treaty affecting the new ships. The President approved the work be immediately suspended on the eight superdreadnoughts and six battle cruisers. It is estimated the building operations thus halted have cost the government approximately $5,000,000 a month.

Contracts to Be Canceled.

Following ratification of contracts for the new ships will be canceled. The ultimate cost of this cancellation cannot be determined in advance, but naval officials believe that a considerable saving will be made through yesterday’s action.

Only one capital ship under construction was exempted from the suspension order. She is the Colorado, more than 90 percent complete, and which will be retained in the permanent fleet.”

What about the men?

From the same article, members of the House naval committee reported that there was a strong sentiment for a sharp reduction in naval personnel. While some felt 100,000 should be sufficient, with the large cuts, many felt a base force of 50,000 would be sufficient.

Just as significant, the Navy stopped working on fortifying the far-flung island outposts such as Guam and Wake and cancelled orders for strengthening the defenses of the Philippine Islands.

From the Navy History Web Site:

During the Inter-War Period, the large fleet consolidated first in 1919 into two equally sized Atlantic and Pacific Fleets to prepare to counter either Great Britain or Japan and then in 1922 into a single United States Fleet largely based on the West Coast to counter Japan. Avoiding forward deployments that were perceived as provocative, the U.S. Fleet focused on annual fleet exercises and experiments near the United States. The fleet was only deployed forward once this period, to Australia and the southwest Pacific in 1925, which elicited significant criticism from Japan.

While this was taking place, the United States and most of the other nations tried their best to follow the rules of the first conference.

Japan however was already secretly preparing its forces to extend her influence in the east Asian areas. It was evident from the beginning that they were going to spend as much energy as possible on developing weapons and tactics that could someday take advantage of the loopholes in the treaty. America and Britain’s focus on battleship and gun size would take away some of the focus on air power and expansion. Just as it did before the Great War, the Navy would someday find itself playing a dangerous game of catch up that would have enormous impact on strategy and tactics.

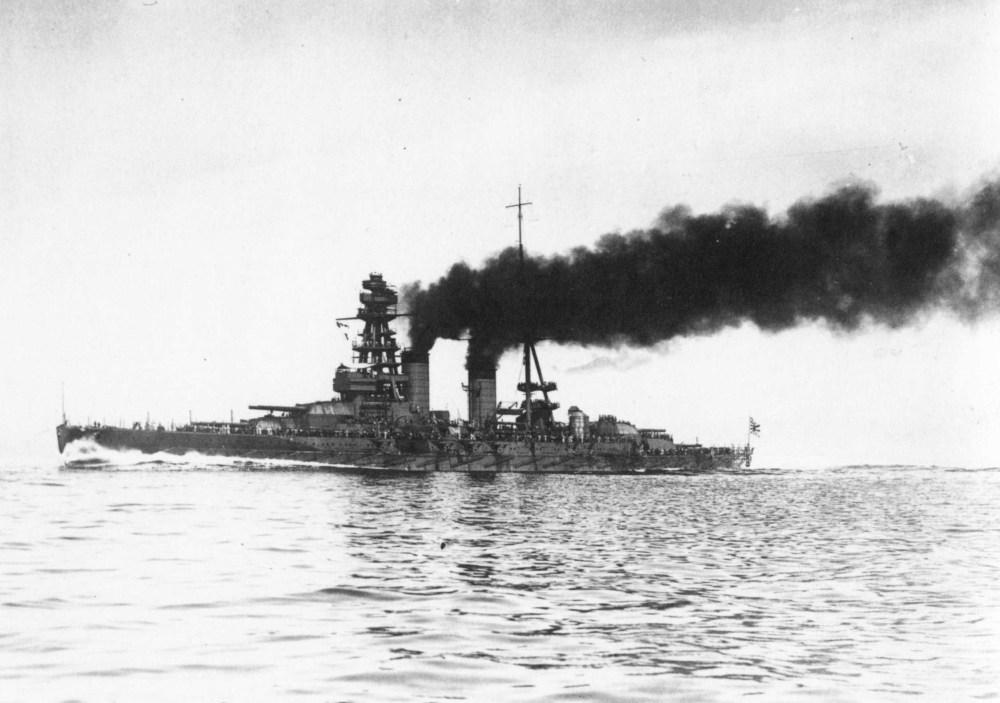

In the 1920s, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was a significant force in naval warfare, particularly in the Pacific. The IJN was the third largest navy in the world by 1920, following the United States Navy and the Royal Navy. The navy’s development was marked by several successes in combat, including engagements in the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War. The IJN also fielded limited land-based forces, including professional marines, marine paratrooper units, anti-aircraft defense units, and naval police units. The navy’s modernization efforts were supported by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service for reconnaissance and airstrike operations from the fleet.

The Imperial Japanese Navy was faced before and during World War II with considerable strategic challenges, probably more so than any other navy in the world.

Japan, like Britain, was almost entirely dependent on foreign resources to supply its economy. In order to achieve Japan’s expansionist policies, the IJN therefore had to secure distant sources of raw material (especially Southeast Asian oil and raw materials), controlled by foreign countries (Britain, France, and the Netherlands), and secure their seaborne transport back to the Home Islands. Japanese planners assessed that building large warships capable of long-range operations was the best way to achieve these goals. In the years before World War II, the IJN began to structure itself specifically to challenge American naval power in the Pacific. Throughout the 1930s, Japanese politics became increasingly dominated by militaristic leaders who prioritized territorial expansion, and who eventually came to view the United States as Japan’s main obstacle to achieving this goal.

The Decisive Battle Doctrine

Japanese naval planners subscribed to a doctrine of “decisive battle” (艦隊決戦, Kantai Kessen), which stipulated that Japan’s path to victory against a peer adversary at sea required the IJN to comprehensively destroy the bulk of an enemy’s naval strength in a single, large-scale fleet action. Kantai kessen evolved from the writings of geopolitical theorist Alfred T. Mahan, which hypothesized that wars would be decided by large, decisive engagements at sea between opposing surface fleets. Derived from the writings of Satō (who was doubtless influenced by Mahan), Kantai Kessen was the basis of Japan’s demand for a 70% ratio (10:10:7) at the Washington Naval Conference, which Japanese naval planners believed would give the IJN superiority in the “decisive battle area”, and the US’s insistence on a 60% ratio, which meant parity between the two navies. In the specific case of a hypothetical war with the United States, this “decisive battle” doctrine required the U.S. Navy to sail in force across the Pacific, during which it would be harassed and degraded by Japanese submarines, and then engaged and destroyed by IJN surface units in a “decisive battle area” somewhere in waters close to Japan.

Japan’s numerical and industrial inferiority to rivals such as the United States led the Japanese leadership to pursue technical superiority (fewer, but faster, more powerful ships), qualitative superiority (better training), and aggressive tactics (daring and speedy attacks overwhelming the enemy, a recipe for success in previous conflicts). However, these calculations failed to account for the type of war Japan would be fighting against an enemy like the U.S. Japan’s opponents in any future Pacific War would not face the political and geographical constraints that adversaries in previous wars did, and Japanese strategic planning did not properly account for serious potential losses in ships and crews.

During the interwar years, two schools of thought emerged over whether the IJN should be organized around powerful battleships, ultimately able to defeat equivalent American ships in Japanese waters, or whether the IJN should prioritize naval airpower and structure its planning around aircraft carriers. Neither doctrine prevailed, resulting in a balanced yet indecisive approach to capital ship development.

A consistent weakness of Japanese warship development was the tendency to incorporate excessive firepower and engine output relative to ship size, which was a side-effect of the Washington Treaty limitations on overall tonnage. This led to shortcomings in stability, protection, and structural strength.

The Circle Plans

In response to the London Treaty of 1930, the Japanese initiated a series of naval construction programs or hoju keikaku (naval replenishment, or construction, plans), known unofficially as the maru keikaku (circle plans). Between 1930 and the outbreak of the Second World War, four of these “Circle plans” which were drawn up: in 1931, 1934, 1937 and 1939. The Circle One was plan approved in 1931, provided for the construction of 39 ships to be laid down between 1931 and 1934, centering on four of the new Mogami-class cruisers, and the expansion of the Naval Air Service to fourteen air groups. However, plans for a second Circle plan were delayed by the capsizing of the Tomozuru and heavy typhoon damage to the Fourth Fleet, which revealed that the fundamental design philosophy of many Japanese warships was flawed. These flaws included poor construction techniques and structural instability caused by mounting too much weaponry on too small of a displacement hull. As a result, most of the naval budget in 1932–1933 was absorbed by modifications that attempted to rectify these issues with existing equipment.

In 1934, the Circle Two plan was approved, covering the construction of 48 new warships, including the Tone-class cruisers and two aircraft carriers, the Sōryū and Hiryū. The plan also continued the buildup in naval aircraft and authorized the creation of eight new Naval Air Groups. With Japan’s renunciation of previously signed naval treaties in December 1934, the Circle Three plan was approved in 1937, marking Japan’s third major naval building program since 1930. Circle Three called for the construction of new warships that were free from the restrictions of previous naval treaties over a period of six years. New ships would concentrate on qualitative superiority in order to compensate for Japan’s quantitative deficiencies compared to the United States. While the primary focus of Circle Three was to be the construction of two super-battleships, Yamato and Musashi, it also called for building the two Shōkaku-class aircraft carriers, along with sixty-four other warships of other categories. Circle Three also called for the rearming of the decommissioned battlecruiser Hiei and the refitting of her sister ships Kongō, Haruna, and Kirishima. Also funded was the upgrading of four Mogami-class cruisers and two Tone-class cruisers, which were under construction, by replacing their 6-inch main batteries with 8-inch guns. In aviation, Circle Three aimed at maintaining parity with American naval air power by constructing an additional 827 planes, to be allocated between fourteen planned land-based air groups, and increasing carrier aircraft by nearly 1,000. To accommodate the new land aircraft, the plan called for several new airfields to be built or expanded; it also provided for a significant increase in the size of the navy’s production facilities for aircraft and aerial weapons.

In 1938, with Circle Three under way, the Japanese began to consider preparations for a fourth naval expansion project, which was scheduled for 1940. With the American Naval Act of 1938, the Japanese accelerated the Circle Four six-year expansion program, which was approved in September 1939. Circle Four’s goal was doubling Japan’s naval air strength in just five years, delivering air superiority in East Asia and the western Pacific. It called for the building of two Yamato-class battleships, a fleet carrier, six of a new class of planned escort carriers, six cruisers, twenty-two destroyers, and twenty-five submarines.

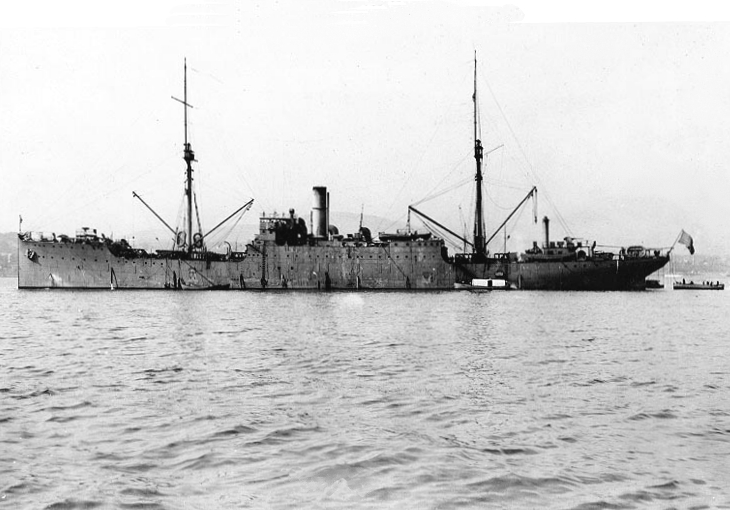

Cassin Young returned to submarines to help place in commission the USS S-51 (SS-162) was a fourth group (S-48) S-class submarine of the United States Navy.

Her keel was laid down on 22 December 1919 by the Lake Torpedo Boat Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut. She was launched on 20 August 1921 sponsored by Mrs. R.J. Mills. Lt. Young was assigned as the Executive Officer of this new submarine and took charge of fitting her out for her eventual commissioning.

An unexpected event in December would bring the dangerous nature of submarining to the front of the public’s attention once more.

The USS S-48 was another new construction boat that was just ahead of the 51 boat. On December 5th, 1921, she was conducting sea trials with a mixed Navy and civilian crew on board when she inadvertently sunk at 4 o’clock in the afternoon because of a large volume of water entering the after-ballast tanks. The crew were unable to counter the additional weight, and the boat quickly sank by the stern with her nose protruding through the surface. Over the next six hours, the prospective Captain and crew with the aid of the shipyard people tried everything possible to pump out the water but to no avail. In the end, a decision was made that some of them should escaper through the forward torpedo tubes and try and hail a passing ship.

This unusual maneuver was successful in placing men on the outside of the boats. They tried burning mattresses to gain any attention they could but in the end, it was a hand lantern flashing to a passing tug that finally brought rescue. Not a single person was lost in the incident and eventually, the boat would be salvaged to serve again. The resulting investigation revealed that several of the plates had not been installed allowing uncontrolled flooding in the after compartments. The end result could have been much different since the boat’s batteries were exposed to sea water and chlorine gas was slowly building up. Lieutenant Commander Walter S. Haas was the prospective commanding officer at the time of the incident. In January of 1922, he was transferred to the USS S-51 as the new prospective commanding officer. This would be the second time his path crossed with Lt. Young. He had been Young’s original submarine commander on the old R-22.

The two men worked together to make the 51 boat ready for service and both transferred to the Navy Department in the early part of 1923.

The USS S-51 eventually suffered a catastrophe that eclipsed her sister ship the S-48. On the night of September 25, 1925, she was underway and was struck by a merchant ship “The City of Rome”. Only three men out of the thirty-six on board escaped a watery depth this time. The remaining crew went down with the ship which remained on the bottom until salvaged the following July by a team led by then-Lieutenant Commander (later Rear Admiral) Edward Ellsberg. The entire salvage operation was commanded by Captain (later Fleet Admiral) Ernest J. King. She was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 27 January 1930 and sold for scrap on 23 June to the Borough Metal Company of Brooklyn, New York.

In 1925, the USS Vestal (the previous collier that had been converted to a repair ship) underwent a modification that changed her from a coal-powered ship to an oil-fired one. On that fateful day in September when the submarine USS S-51 was rammed and sunk by SS City of Rome, the Vestal was called to help recover the submarine. Vestal conducted her salvage operations from October to early December 1925 and again from 27 April to 5 July 1926. During the latter period, the submarine was raised from her watery grave. Following the completion of recovery, Vestal was transferred to the Pacific Fleet in 1927. She would remain largely in the Pacific and someday be commanded by another former submariner in 1941: Cassin Young.