Chapter 11: Mosquitos, sand flies and ants shall inherit the earth

“Information on living conditions in the Canal Zone. Atlantic Side.

Any officer ordered to the Canal Zone should, if possible, leave his family in the States until he has investigated the situation described above”

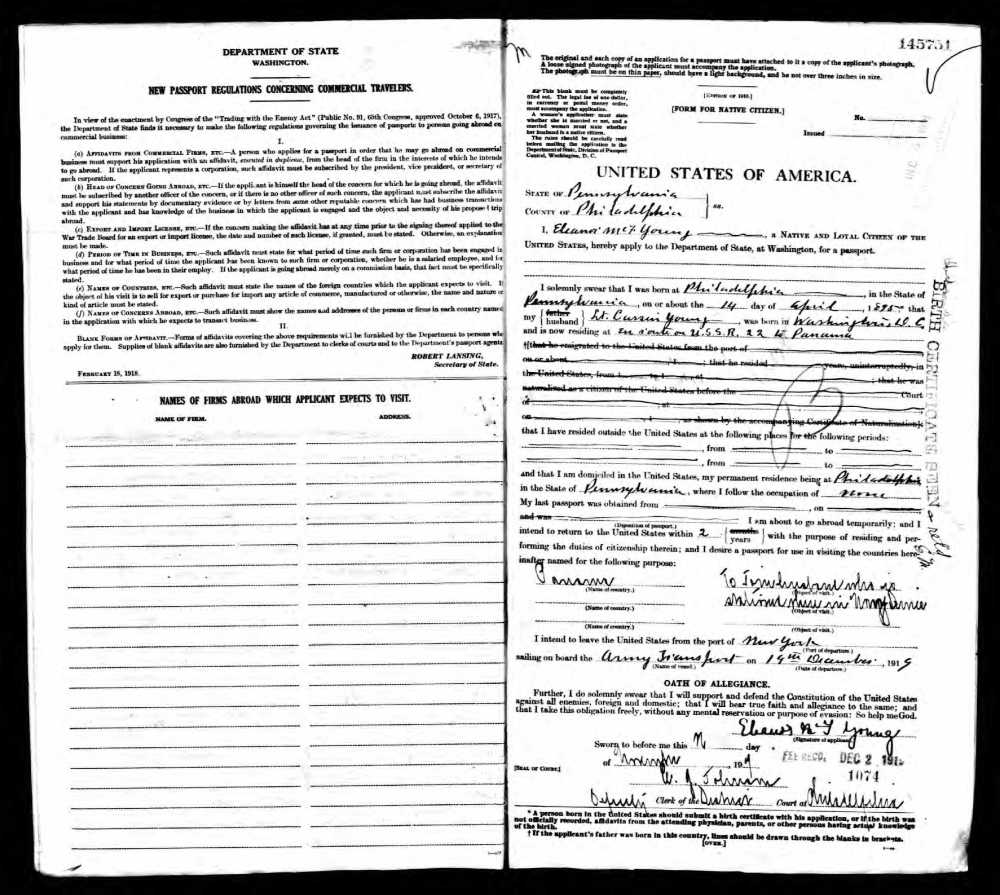

These words of caution were written in a pamphlet published by the Navy a year after Lt. Cassin Young and his submarine were ordered to the submarine base at Coco Solo in the Panama Canal Zone. Conditions at the primitively furnished base would set the tone for many of the assignments Cassin would receive with his family over the next twenty years.

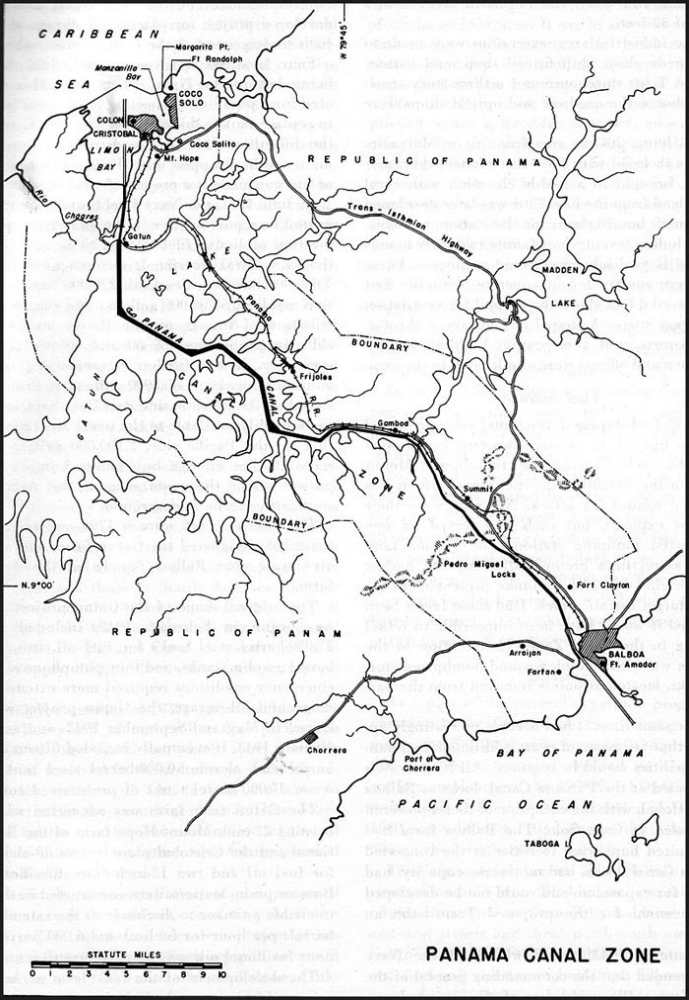

The journey to Coco Solo was always done by boat in the 1920’s. There were a number of ships belonging to the United Fruit companies and the Canal Zone Company. Each offered a variety of levels of services and a number of amenities. The other alternative would be to sail on an Army transport ship in a vessel that had just recently been used to ferry the hundreds of thousands of Dough Boys back from the recent war in Europe. All of the vessels would end their journey in one of the warmest places in the northern hemisphere. Panama had become an important part of America with the building and opening of the Panama Canal. This strategic resource was built to allow the largest ships in the American battle fleet to travel more quickly from one ocean to another. A lot of American treasure went into building and maintaining the canal. When it officially opened in July of 1920, it stood as the most expensive engineering project the country had ever entered into.

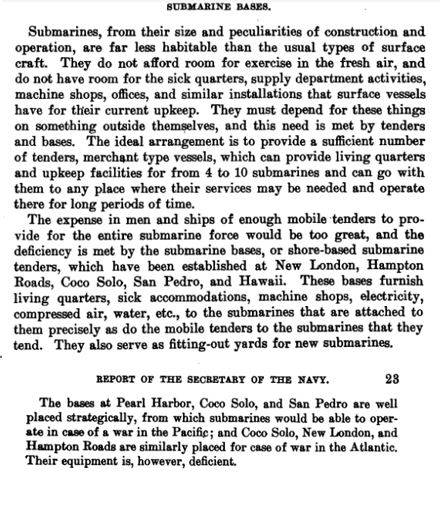

The importance of the canal was not lost on anyone. A rogue attack on any part of the system could have a serious impact on the nation’s ability to defend itself. The rise of the Japanese in the east was an ever-present threat now that the war in Europe was over. Relations between America and Japan had soured in recent years as the American government reacted to the presences of Japanese in California and Hawaii in a way that hurt relations between the two powers. Protectionism was the word of the day in Congress and laws that restricted Japan’s ability to emigrate and flourish in the country were odious and unpleasant to the Japanese frame of mind. Their ambitions for more territory were already becoming a problem for the old powers and that spelled trouble in the Pacific regions.

The American fleet, while stronger than it had ever been, still had to contend with the two ocean threat. As peace seemed to settle in Europe, there was trouble in the fledgling Soviet Union and the Sino-Japanese question was on the fronts of everyone’s strategic mindset. The canal was important to allow the US Navy to respond more quickly to whatever threat which might emerge. Defending that resource became a very important job for the US Navy and US Army. On the Atlantic side, that included both Army forts and Navy bases that included submarines and air wings. The little ships and planes that were once viewed as a side show and distraction suddenly gained a new level of importance in a post war period. Both were less expensive to build and maintain than a large surface fleet and both could provide the needed defense against any potential enemies that might threaten the canal.

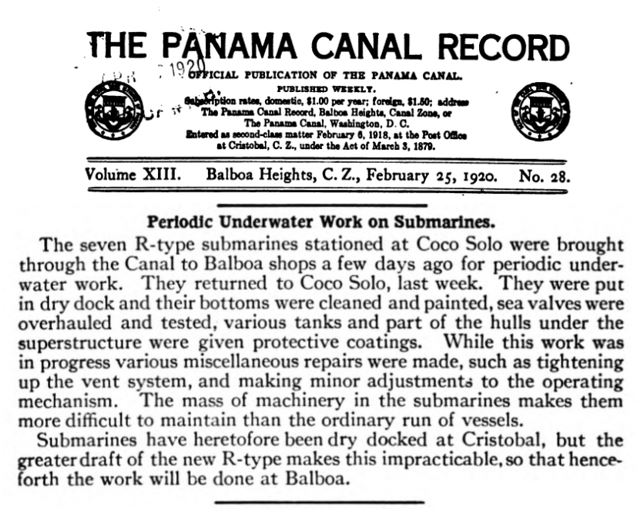

First Official Duty Station

Mrs. Cassin Young sailed south on the nineteenth of December 1919 on an Army transport ship to join her husband who was serving on the submarine USS R-22. Because of the boat’s schedule, she would spend her first Christmas as an officer’s wife at sea without him there. The R-22 had already sailed south for the warmer climate of Coco Solo, C.Z on November 1, and arrived in early December. The tropical port would serve as her new homeport along with her sister ships of Squadron 1 providing part of the security duty for the east end of the relatively new canal. She was re-designated as the SS-99 in July 1920. These small boats were some of the newest the Navy had at the time but were still very limited in their ability to operate on the open ocean. This unfortunate fact actually made them the ideal candidates to replace the older class submarines that were already present.

The shock of arriving in a tropical location must have been tremendous. After years of living in a civilized world where customs and traditions were matched with well-regulated infrastructure, the women who came to join their husbands at the new submarine base would find many challenges. The climate was certainly one of the very first things that the newcomer’s would have to get used to. Fortunately for Mrs. Young, she arrived at the beginning of the “dry” season where the weather was a little more moderate and not as rainy. Panama was always hot and even though there were two seasons, the only real difference was the amount of rainfall in the wet season. From December to the middle of April, the rain was not as prominent and travel in the region was not as difficult. After May however, the rains came frequently and with a purpose. Outside of the areas where concrete roads and reinforced railroads had been built by the Panama Canal Company, dirt roads quickly turned to muddy and impassible trails.

The Base at Coco Solo

The base at Coco Solo had just recently been improved from its humble beginnings. In 1920, on the Atlantic side, quarters were sparse and limited. There were government quarters for twenty three married officers and their families and fifty two unaccompanied bachelor officers. Only ten units were reserved for married petty officers. The officers’ quarters faced the ocean approaches to the canal and offered wonderful views of the ships coming into and leaving the zone. Since there climate was tropical, all of the construction was simple and designed to take maximum advantage of the breezes while shielding the occupants from the rain. Shopping for food and dry goods was limited in the days that Mrs. Young first arrived. Since there was no commissary on base (that would come after their tour was completed, families took the bus to the nearby canal commissaries. These stores carried everything the Navy wife might need (to a point) including dry goods, hardware, fresh meat, vegetables and shoes. The climate would dictate a frequent replacement of shoes and the ability to store foods was hampere3d by the limited space and lack of adequate refrigeration.

The twice a day bus ride to the shopping areas was the main way that wives could shop for their supplies. Eggs and milk were only issued on Doctors orders. Frozen milk from the states was available but had to be consumed at one sitting since it spoiled almost as fast as it thawed. The bus rides were very typical of the “caste” system still present in the Navy and Army. The morning trips were reserved for officer’s families and the afternoon for Chief Petty Officer’s families. There was no mixing of the two groups of wives. The advantage the morning trip offered was that it occurred during the cooler hours of the day. None of the buses were equipped with air conditioning of any kind so the afternoon trip would be a bit more difficult to manage. Each family was limited to one trip every other day for shopping.

The Swamp

The land that housed the submarine and air station for the Navy was shared with an Army garrison. In the middle of the two facilities was a swamp that had been there for probably as long as the isthmus existed. This swamp added to the challenges for the small community since it was a breeding ground for one of the worst of all the enemies the sailors and their families would face: the dreaded mosquitos. The mosquito had long been known for its dangerous ability to spread diseases in the tropics. During the building of the canal, as great an effort into finding ways to protect the workers was conducted as the efforts to build any single part of the canal. The answer was always to try and eliminate the breeding grounds where these pesky purveyors of disease flourished. It was not an easy task. In 1920, both the Army and the Navy had to go back to congress to get funds to drain the swamp and make the bases more habitable. In true post war bureaucratic fashion the path to obtaining the nearly one million dollars was almost as torturous as the pests were themselves. But finally, extra finds were added and work was done to eliminate this threat.

The elimination of mosquitos was only one of the pests that would plague the families as they lived in this new paradise. Stinging black flies and armies of ants would be a constant reminder that all of the warm weather and sunshine comes at a cost. The officer’s quarters were built especially for the tropical conditions and were spacious and well ventilated buildings with wide verandas extending around three sides of the multi-story house and across the front of the single story homes. All of the openness invited the breezes and the insects. But like any service family from any generation, the families would soon learn to overcome even these shortfalls and live lives that were pleasant and memorable.

From the Secretary of the Navy’s 1920 Report:

“Naval air station and submarine base, Coco Solo, Canal Zone. The general health of the personnel has been good, with the exception disability due to malaria. This infection must be expected, due to the large swamp immediately adjacent to the station. A special appropriation enables, for the time being, the employment of nine laborers and three mosquito catchers in fighting the malaria situation. Constant work is necessary to clear the land on the station proper, but conditions will never be satisfactory until the swamp adjacent to the station is filled. The laborers are engaged in clearing away vegetation, oiling accumulations of water, keeping screening intact, and catching mosquitoes. One hospital corpsman is detailed exclusively to superintend these operations. – Lieut. W. S. LEAVENWORTH Medical Corps, United States Navy”.

The Life of an Officer’s Wife

If Mrs. Young had any illusions about being an officer’s wife in a land of paradise, those illusions must have been shattered pretty quickly. Coco Solo in 1920 was just at the beginning of its real growth and dirt and dust were everywhere as the buildings and roads were being constructed. The dwellings were bare of any feminine touch as well. Naval planners had laid out what seemed like adequate quarters that would be purposeful and Spartan in nature. The Navy bulletin informed the new arrivals that “Each house is furnished with two Crex druggets, dining room table and chairs, wicker upholstered chairs, and plain wicker chairs for the verandas. Each bedroom is equipped with white enameled bed, two chairs and a bureau. The kitchen is equipped with a coal stove and two chairs.” (The crex druggets mentioned were rugs that were popular during the early part of the twentieth century.) Ice was purchased form the Panama Canal Company and delivered to the houses once a day at a cost of forty cents a hundred pounds.

One small advantage for the more well-to-do wives was the system of servants available. Only Jamaican females were employed but they were required to be English speakers. Good cooks would cost sixteen to twenty dollars a month, maids for fifteen to eighteen, and nurse girls for twelve to sixteen dollars a month. The advantage of these amenities were that the officer’s wives could have some semblance of their former lives in the states which included playing cards with their fellow officer’s wives and the occasional game of tennis.